I have a fish, and his name is Gil, and he eats quite a bit. The question of what Gil eats (and where he gets it from) is interesting to me as a data science problem. Why? Our story starts with the unfortunate reality (for my fish) that I am allergic to being domestic: the extent that I will “cook” is cutting up vegetables and then microwaving them for a salad feast. This is problematic for someone who likes to eat many different things, and so the solution is that I have a lot of fun getting Gil food from many of the nice places to eat around town. Given that this trend will likely continue for many years, and given that we now live in the land of infinite culinary possibilities (Silicon Valley programmers are quite eclectic and hungry, it seems), I wanted a way to keep a proper log of this data. I wanted pictures, locations, and reviews or descriptions, because in 5, 10, or more years, I want to do some awesome image and NLP analyses with these data. Step 1 of this, of course, is collecting the data to begin with. I knew I needed a simple database and web interface. But before any of that, I needed a graphical representation of my Gil fish:

Goals

My desire to make this application goes a little bit deeper than keeping a log of pictures and reviews. I think pretty often about the lovely gray area between data analysis, web-based tools, and visualization, and it seems problematic to me that a currently highly desired place to deploy these things (a web browser) is not well fit for things that are large OR computationally intensive. If I want to develop new technology to help with this, I need to first understand the underpinnings of the current technology. As a graduate student I’ve been able to mess around with the very basics, but largely I’m lacking the depth of understanding that I desire.

On what level are we thinking about this?

When most people think of developing a web application, their first questions usually revolve around “What should we put in the browser?” You’ll have an intimate discussion about the pros and cons of React vs. Angular, or perhaps some static website technology versus using a full fledged server (Jekyll? Django? ClojureScript? nodeJS?). What is completely glossed over is the standard that we start our problem solving from within the browser box, but I would argue that this unconscious assumption that the world of the internet is inside of a web browser must be questioned. When you think about it, we can take on this problem from several different angles:

From within the web browser (already discussed). I write some HTML/Javascript with or without a server for a web application. I hire some mobile brogrammers to develop an Android and iOS app and I’m pouring in the sheckles!

Customize the browser. Forget about rendering something within the constraints of your browser. Figure out how the browser works, and then change that technology to be more optimized. You might have to work with some standards committees for this one, which might take you decades, your entire life, or just never happen entirely.

Customize the server such as with an nginx (pronounced “engine-X”) module. Imagine, for example, you just write a module that tells the server to render or perform some other operation on a specific data type, and then serve the data “statically” or generate more of an API.

The Headless Internet. Get rid of the browser entirely, and harness the same web technologies to do things with streams of data, notifications, etc. This is how I think of the future - we will live in a world where all real world things and devices are connected to the internet, sending data back and forth from one another, and we don’t need this browser or a computer thing for that.

There are so many options!

How does a web browser work?

I’ve had ample experience with making dinky applications from within a browser (item 1) and already knew that was limited, and so my first thinking was that I might try to customize a browser itself. I stumbled around and found an amazing overview. The core or base technology seems simple - you generate a DOM from static syntax (HTML) files, link some styling to it based on a scoring algorithm, and then parse those things into a RenderTree. The complicated part comes when the browser has to do a million checks to walk up and down that tree to find things, and make sure that the user (the person who wrote the syntax) didn’t mess something up. This is why you can have some pretty gross HTML and it still renders nicely, because the browser is optimized to handle a lot of developer error before passing on the “I’m not loading this or working” error to the user. I was specifically very interested in the core technology to generate parsers, and wound up creating a small one of my own. This was also really good practice because knowing C/C++ (I don’t have formal CS training so I largely don’t) is something else important to do. Python is great, but it’s not “real” programming because you don’t compile anything. Google is also on to this, they’ve created Native Client to run C/C++ natively in a browser. I’m definitely going to check this out soon.

I thought that it would be a reasonable goal to first try and create my own web browser, but reading around forums, this seemed like a big feat for a holiday weekend project. This chopped item #2 off of my list above. Another idea would be to create a custom nginx module (item #3) but even with a little C practice I wasn’t totally ready this past weekend (but this is definitely something I want to do). I realized, then, that the best way to understand how a web browser worked would be to start with getting better at current, somewhat modern technology. I decided that I wanted to build an application with a very specific set of goals.

The Goals of Gil Eats

I approached this weekend fun with the following goals. Since this is for “Gil Eats” let’s call them geats:

- I want to learn about, understand, and implement an application that uses Javascript Promises, Web Workers (hello parallel processing!), and Service Workers (control over resources/caching).

- The entire application is served statically, and the goal achieved with simple technology available to everyone (a.k.a, no paying for an instance on AWS).

- Gil can take a picture of his dinner, and upload it with some comments or review.

- The data (images and comments) are stored in a web-accessible (and desktop-accessible, if desired) location, in an organized fashion, making them immediately available for further (future!) analysis.

This was a pretty hefty load for just a holiday weekend, but my excitement about these things (and continually waking up in the middle of the night to “just try one more thing!”) made it possible, and I was able to create Gil Eats.

Let’s get started!

My Workflow

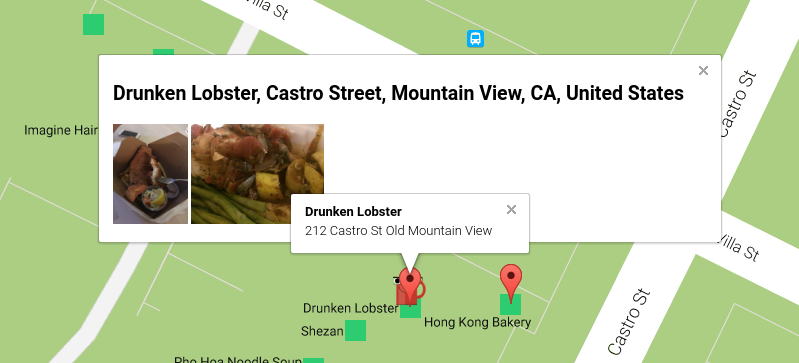

I never start with much of a plan in mind, aside from a set of general application goals (listed above). The entire story of the application’s development would take a very long time to tell, so I’ll summarize. I started with a basic page that used the Dropbox API to list files in a folder. On top of that I added a very simple Google Map, and eventually I added the Places API to use as a discrete set of locations to link restaurant reviews and photos. The “database” itself is just a folder in Dropbox, and it has images, a json file of metadata associated with each image, and a master db.json file that gets rendered automatically when a user visits the page (sans authentication), and updated when a user is authenticated and fills out the form. I use Web Workers to retrieve all external requests for data, and use Service Workers to cache local files (probably not necessary, but it was important for me to learn this). The biggest development in my learning was with the Promises. With Promises you can get rid of “callback hell” that is (or was) definitive of JavaScript, and be assured that one event finishes before the next. You can create a single Promise that takes two handles to resolve (aka, woohoo it worked here’s the result!), or reject (nope, it didn’t work, here’s the error), or do things like chain promises or wrap them in calling functions. I encourage you to read about these Promises, and give them a try, because they are now native in most browsers, and (I think) are greatly improving the ease of developing web applications.

Now let’s talk a bit about some of the details, and problems that I encountered, and how I dealt with them.

The Interface

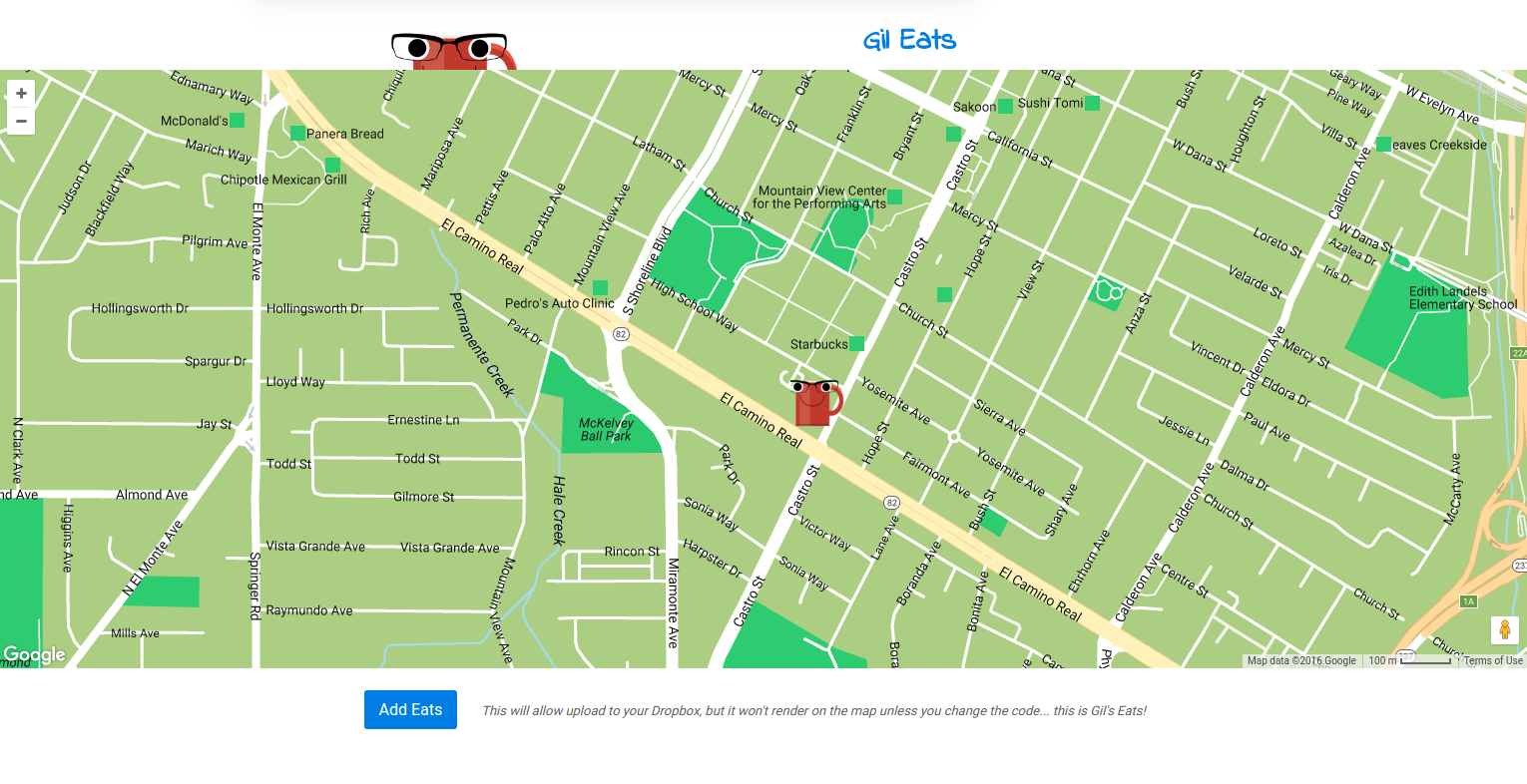

The most appropriate visualization for this goal was a map. I chose a simple “the user is authenticated, show them a form to upload” or “don’t do that” interface, which appears directly below the map.

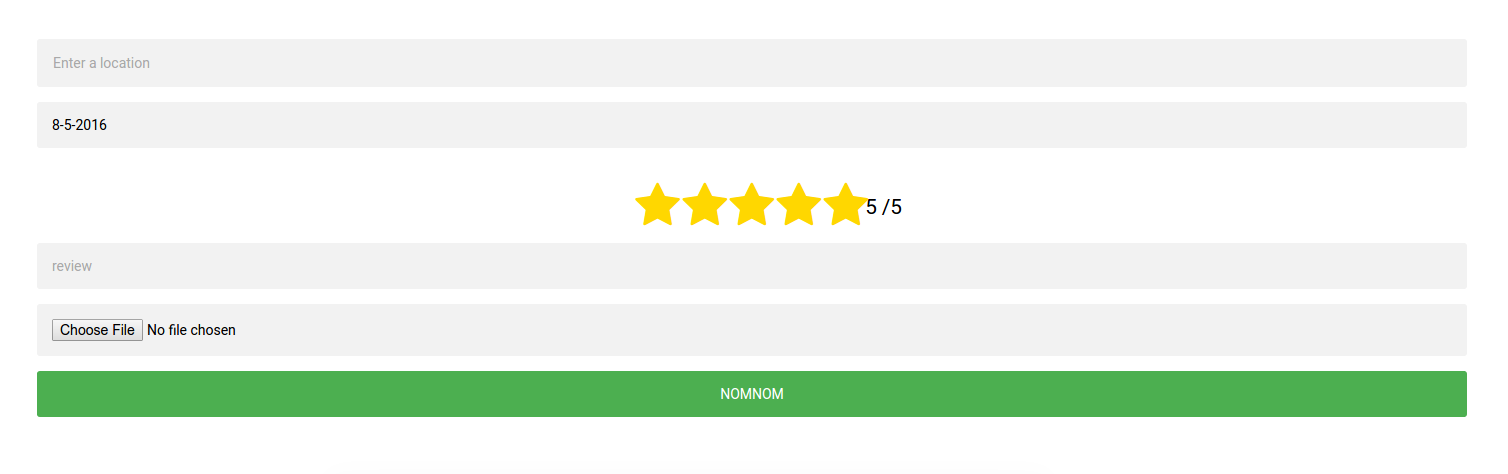

The form looks like this:

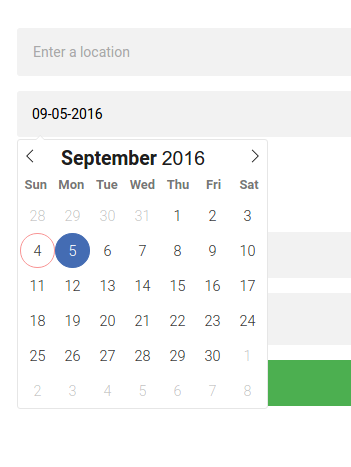

The first field in the form is linked with the Google Maps Places API, so when you select an address it jumps to it on the map. The date field is filled in automatically from the current date, and the format is controlled by way of a date picker:

You can then click on a place marker, and see the uploads that Gil has made:

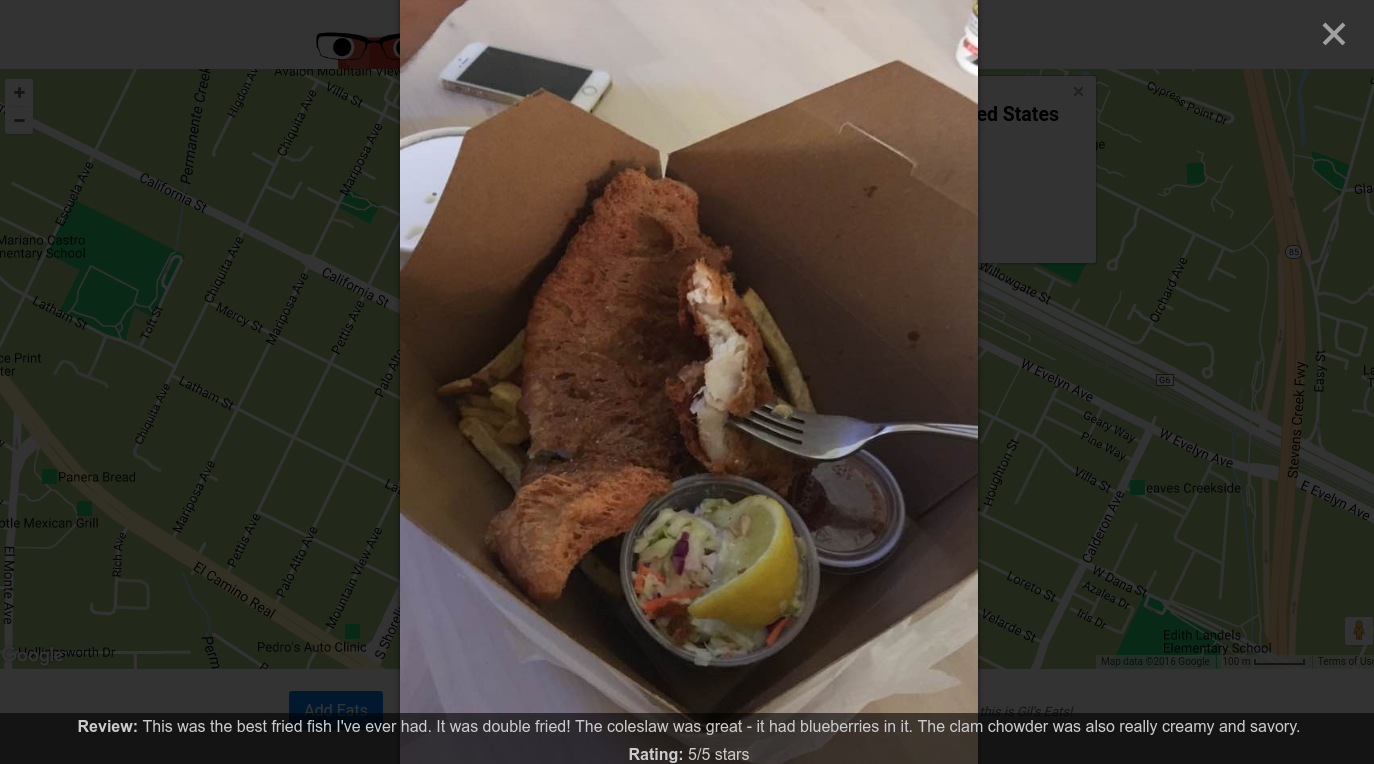

If you click on an image, of course it’s shown in all its glory, along with Gil’s review and the rating (in stars):

Speaking of stars, I changed the radio buttons and text input into a custom stars rating, which uses font awesome icons, as you can see in the form above. The other great thing about Google Maps is that you can easily add a Street View, so you might plop down onto the map and (really) see some of the places that Gil has frequented!

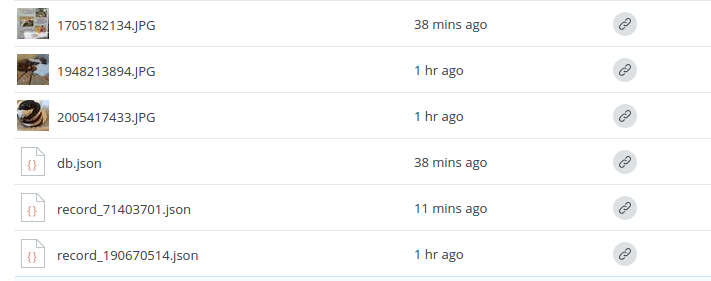

The “database”

Dropbox has a nice API that let me easily create an application, and then have (Gil) authenticate into his account in order to add a restaurant, which is done with the form shown above. The data (images and json with comments/review) are saved immediately to the application folder:

How is the data stored?

When Gil uploads a new image and review, it’s converted to a json file, a unique ID is generated based on the data and upload timestamp, and the data and image file are both uploaded to Dropbox with an API call. At the same time, the API is used to generate shared links for the image and data, and those are written into an updated master data file. The master data file knows which set of flat files belong together (images rendered together for the same location) because the location has a unique ID generated based on its latitude and longitude, which isn’t going to change because we are using the Places API. The entire interface is then updated with new data, down to closing the info window for a location given that the user has it open, so he or she can re-open it to see the newly uploaded image. If a user (that isn’t Gil) logs into the application, the url for his or her new database is saved to a cookie, so (hopefully) it will load the correct map the next time he or she visits. Yes, this means that theoretically other users can use Gil’s application for their data, although this needs further testing.

A Flat File Database? Are you nuts?

Probably, yes, but for a small application for one user I thought it was reasonable. I know what you are thinking: flat file databases can be dangerous. A flat file database that has a master file for keeping a record of all of these public shared links (so a non authenticated person, and more importantly, anyone who isn’t Gil) can load them on his or her map means that if the file gets too big, it’s going to be slow to read, write, or just retrieve. I made this decision for several reasons, the first of which is that only one user (Gil) is likely to be writing to it at once, so we won’t have conflicts. The second is that it will take many years for Gil to eat enough to warrant the db.json file big enough to slow down the application (and I know he is reading this now and taking it as a personal challenge!). When this time comes, I’ll update the application to store and load data based on geographic zones. It’s very easy to get the “current view” of the box in the Google Map, and I already have hashes for the locations, so it should be fairly easy to generate “sub master” files that can be indexed based on where the user goes in the map, and then load smaller sets of data at once.

Some application Logic

- The minimum required data to add a new record is an image file and an address.

- I had first wanted to have only individual files, and then load them dynamically based on knowing some Dropbox folder address. Dropbox doesn’t actually let you do this - each file has to have it’s own “shared” link. When I realized this, I came up with my “master database” file solution, but then I was worried about writing to that file and potentially losing data if there was an error in that operation. This is why I made the application so that the entire master database can be re-generated fairly easily. A record can be added or deleted in the user’s Dropbox, and the database will update to not have it.

- A common bug I encountered: when you have a worker running via a Promise, the Promise will only be resolved if you post a message back. I forgot to do this and was getting pending promise returned. This is the same case if you have chained or Promises inside of other promises - you have to return something or the (final) returned variable is undefined.

Things I Learned

Get rid of JQuery

It’s very common (and easy) to use JQuery for really simple operations like setting cookies, and easily selecting divs. I mean, why would I want to do this:

var value = document.selectElementById("answer").value;

When I can do this?

var value = $("#answer").val();

However, I realized that, for my future learning and being a better developer, I should largely try to develop applications that are simple (and don’t use JQuery). Don’t get me wrong, I like it a lot, but it’s not always necessary, and it’s kind of honkin’.

Better Organize Code

The nice thing about Python, and most object-oriented programming languages, is that the organization of the code, along with dependencies and imports, is very intuitive to me. JavaScript is different because it feels like you are throwing everything into a big pot of soup, all at once, and it’s either floating around in the pot somewhere or just totally missing. This makes variable conflicts likely, and I’ve noticed makes it very easy to write poorly documented, error-prone, and messy code. I tried to keep things organized as I went, and at the end was overtaken with my code’s overall lack of simplicity. I’m going to get a lot better at this. I want to get intuition about how to best organize, and write better code. The overall goal seems like it should be to take a big, hairy function and split it into smaller, modular ones, and then reuse them a lot. I need to also learn how to write proper tests for JS.

Think about the user

When Gil was testing it, he was getting errors in the console that a file couldn’t be created, because there was a conflict. This happened because he was entering an image and data in the form, and then changing just the image, and trying to upload again. This is a very likely use case (upload a picture of the clam chowder, AND the fried fish, Romeo!), but I didn’t even think of it when I was generating the function for a unique id (only based on the other fields in the form). I then added a variable that definitely would change, the current time stamp with seconds included. I might have used the image name, but then I was worried that a user would try to upload images with the same name, for the same restaurant and review. Anyway, the lesson is to think of how your user is going to use the application!

Think about the platform

I didn’t think much about where Gil might be using this, other than his computer. Unfortunately I didn’t test on mobile, because the Places API needs a different key depending on the mobile platform. Oops. My solution was to do a check for the platform, and send the user to a “ruh roh” page if he or she is on mobile. In the future I will develop a proper mobile application, because this seems like the most probably place to want to upload a picture.

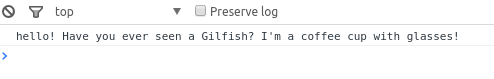

Easter Eggs

I’m closing up shop for today (it’s getting late, I still need to get home, have dinner, and then wake up tomorrow for my first day of a new job!! :D) but I want to close with a few fun Easter Eggs! First, if you drag “Gil” around (the coffee cup you see when the application starts) he will write you a little message in the console:

The next thing is that if you click on “Gil” in Gil's Eats you will turn the field into an editable one, and you can change the name!

…and your edits will be saved in localStorage so that the name is your custom one next time:

function saveEdits() {

var editElem = document.getElementById("username");

var username = editElem.innerHTML.replaceAll('<br>','');

localStorage.userEdits = username;

editElem.innerHTML = username;

}

el = document.getElementById("username");

el.addEventListener("contentchange", saveEdits, false);

and the element it operates on is all made possible with a

contenteditable="true" onkeyup="saveEdits()

in the tag. You’ll also notice I remove any line breaks that you add. My instinct was to press enter when I finished, but actually you click out of the box.

Bugs and Mysteries, and Conclusions

I’m really excited about this, because it’s my first (almost completely working) web application that is completely static (notice the github pages hosting?) and works with several APIs and a (kind of) database. I’m excited to learn more about creating custom elements, and creating object oriented things in JavaScript. It’s also going to be pretty awesome in a few years to do some image processing and text analysis with Gil’s data! Where does he go? Can I predict the kind of food or some other variable from the review? Vice versa? Can the images be used to link his reviews with Yelp? Can I see changes in his likes and dislikes over time? Can I predict things about Gil based on his ratings? Can I filter the set to some subset, and generate a “mean” image of that meal type? I would expect as we collect more data, I’ll start to make some fun visualizations, or even simple filtering and plotting. Until then, time to go home! Later gator! Here is Gil Eats

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Gil Eats." @vsoch (blog), 05 Sep 2016, https://vsoch.github.io/2016/gileats/ (accessed 30 Sep 25).