If you maintain or belong to a GitHub organization, it can be hard to find things. Let’s use my example. I was developing a Community Template for the US Research Software Engineers (US-RSE) community, and specifically, I imagined some future where a user would go to a search portal, and find a Research Software Engineer with specific expertise, or affiliation to help. Given that there are a collection of community repositories (each describing RSEs for some group) I’d want to not just search on one site, but across sites. How could I do this?

In a Nutshell

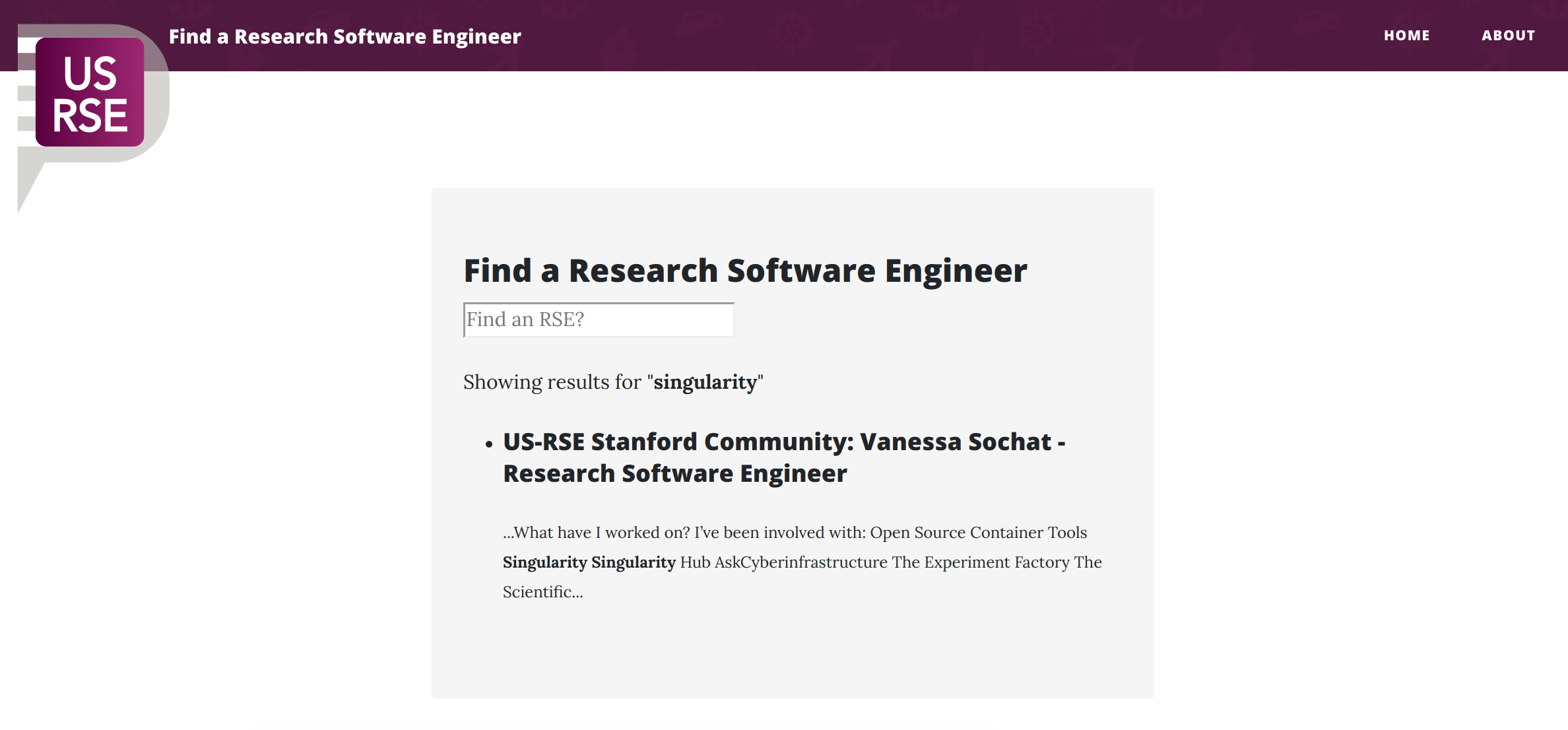

The best way to start is to show you the result! Here is the simple interface for a repository that serves a single purpose to aggregate community data. The sites aren’t developed yet, but if you search for “Singularity” you should find yours truly.

I’ll first quickly review the steps that made this possible, and then show you the details.

- For each repository, generate a data.json template to expose a subset of data to search.

- On a central search page, use the GitHub API to retrieve some filtered set of repository names

- Loop through the set and read the data.json

- Plug into JavaScript Search

Now let’s discuss these in detail.

1. Generate a data.json

Let’s step back and start with a GitHub repository. For any organization, if you use a static site generator like Jekyll, you can put a bunch of style and markdown files on GitHub, enable GitHub pages to deploy from the master branch, and like magic you have a website!

Here is the cool bit - just like you can create a template to render an html page, you can also generate one for a text file, or a json file. Yes, this also means that technically, GitHub pages can serve static (GET) APIs. This is the template that we have here. It might look like a mess, but when we copy pasta the result it renders to into a json validator, we are good:

If you aren’t familiar with the Liquid templating language,

a statement like {{{ var }}} indicates a variable “var”, and a statement like {{% if condition %}}

maps to the opening of a for loop. You can read more about the templating language via the link above,

and here I’ll walk you through some pseudo code for how we parse through the site content.

For each page in the site that aren't flagged for exclusion:

Filter down to some specific subset based on metadata in the front matter

Render an entry in json that includes a key, id, title, categories, url, and content

Front matter is metadata that is defined for a post or page. You can see examples of how this renders in the validated json image above. For the actual names of the fields that you render, this is totally up to you! You’ll just need to customize whatever plugs the data into search to use them (more on this later).

2. Discover Search Data

Great! So let’s imagine we have a few sites spitting out data like this.

You’ll notice a bunch of newlines \n in the content, and this is because it’s the actual

rendering of a page, and this (along with categories and the name) is exactly what we want to search over.

How do we do that?

GitHub Organization API

We first make use of this API endpoint that gives us more metadata about the repositories in the usrse organization than we know to do with. This repository has this html template that does this. Specifically, we add the entries in the data.json to window.data.

window.data = {}

// Here we query the GitHub API for an organization name rendered from _config.yml

$.getJSON("https://api.github.com/orgs/{{ site.github_username }}/repos", {

format: "json"

}).done(function(data) {

console.log("Found repos starting with {{ site.prefix }}:")

$.each(data, function(key, value) {

if (value.name.startsWith("{{ site.prefix }}")) {

// do something with data here

});

}

})

For those of you not familiar with Jekyll, the _config.yml file can also

hold global metadata about the site. In the example above, site.github_username

would correspond to the github_username defined in the _config.yml. site.prefix

corresponds to prefix in the same file, and we use it as a filter for repository

names. Any repository that starts with the prefix “community-“ is a community site. Take

a look here for an example

configuration file with these variables.

Assemble Compiled Data

What do we do in the center of the loop? We add each entry in data.json to

the window.data. One important detail I forgot to mention is that the keys

in the data.json dictionary are namespaced. This means that they are prefixed

with a unique identifier based on the repository they are served from.

For example, us-rse-stanford-community (site identifier) + people-vsoch

(page identifier) would identify the page with my profile. We do this

because if different sites served the same key, one would overwrite the other,

and we don’t want to do that. It’s actually up to you how you choose to implement this.

I had the serving page automatically write the identifier into the data.json

so the search page could parse it without thinking, but if you wanted more control over

the prefixes you could could also generate the prefix during the parsing itself.

Speaking of, let’s take a look at that.

...

var dataurl = "{{ site.domain }}/" + value.name + '/data.json'

$.getJSON(dataurl, {

format: "json"

}).done(function(pages, status) {

if (status == "success") {

$.each(pages, function(key, value) {

window.data[key] = value;

});

}

...

In the above snippet, we assemble a data url to the data.json (given the same GitHub organization, the base URL is the same, usually “[name].github.io”, or a custom CNAME), perform a GET, check for a successful response, and then parse through it to add to the window.data. It’s important to point out that we can do this in the first place because it’s not considered across origin. If you tried to do this across different GitHub organizations, or repositories under different CNAMEs, you would get an ugly cross origin error message. At this point we have assembled data across sites, woot! What do we do now?

3. JavaScript Search

I’ve taken to Lunr.js over the years as a really simple solution to providing search on a static site. You can look at the entire repository to trace how it works, and I’ll again summarize here.

We obviously have to add lunr.min.js to our static files, and then a search.js that is going to expect the data in window.data, and then generate results to append to a div in the page. We start our journey in the same template that prepares the data. The HTML is fairly simple - we create a form to provide a search box. Notice that when the user submits, it performs a GET to itself, and sends the query term to the browser as a GET parameter.

<form action="{{ site.baseurl }}/" method="get">

<input type="search" name="q" id="search-input" placeholder="Find an RSE?" style="margin-top:5px" autofocus>

<input type="submit" value="Search" style="display: none;">

</form>

Note that the input variable name for the search result is “q.” This is what is going

to be sent to the page in the browser as the search query, e.g {{{ site.baseurl }}}/?q=query.

Then we have a “search-process” div that the search.js is going to update with results,

and a “search-query” span that our term will be added to.

<p><span id="search-process">Loading</span> results

<span id="search-query-container" style="display: none;">for "

<strong id="search-query"></strong>"

</span></p>

<ul id="search-results"></ul>

And finally, we add the javascript files to the end of the page, triggering the entire process.

<script src="{{ site.baseurl }}/assets/js/lunr.min.js"></script>

<script src="{{ site.baseurl }}/assets/vendor/jquery/jquery.min.js" ></script>

What happens when search.js runs? Let’s now jump into search.js. First, lunr.js is instantiated at window.index.

window.index = lunr(function () {

this.field("id");

this.field("title", {boost: 10});

this.field("categories");

this.field("url");

this.field("content");

});

This is likely where we set the fields from the data that we want to search, along with other variables for each. Take a look at the documentation to see much simpler examples. It’s a fairly awesome little library.

We then grab the query from the URL, the ?q=mysearchterm. If it doesn’t exist,

we default to the empty string. We also grab the “search-query-container” and

the “search-query” div, and we update both:

var query = decodeURIComponent((getQueryVariable("q") || "").replace(/\+/g, "%20")),

searchQueryContainerEl = document.getElementById("search-query-container"),

searchQueryEl = document.getElementById("search-query");

searchQueryEl.innerText = query;

if (query != ""){

searchQueryContainerEl.style.display = "inline";

}

Finally, we give the window.data (the json entries, one per external page) to the lunr instantiation we created (window.index):

for (var key in window.data) {

window.index.add(window.data[key]);

}

And we call the function “displaySearchResults” that is going to run the search, and then render the matches to the page.

displaySearchResults(window.index.search(query), query);

It goes without saying that for the above, we search across fields, and for each match, since we have a url field, we render that as a link that the user can click. The result is this page.

Summarize!

Wasn’t this fun? Javascript is a bit hairy, and I certainly don’t claim to follow best practices. For example, a lot of (actually proficient) JavaScript developers would not be happy with my use of the window for variables, or even using JQuery to begin with. Regardless, the above is a nice example for how easy it is to break a fugly thing (a combination of jekyll, templates, and scripts) into a story that can be understood.

And guess what, I showed you the more complicated version first! You can totally skip the GitHub API, and parsing data.json files entirely if you just want to add search to a single repository’s site. For example, in the process of designing this, I added a simple search page to us-rse.org. And if you look at the template that renders it, you’ll notice we are writing the data object directly into the page. This is hugely easier.

Why is this important?

I suspect that most GitHub organizations, or even single repositories, don’t provide an easy means to find things. Whether you are serving content that is documentation for your software, or information about people that might provide support, providing this kind of search is essential for the usability of your resource.

Is there only one way to fulfill a Meeseeks? Of course not! I encourage you to explore other ways to implement static search, one example being tipuesearch that I use on the site that you are reading right now. And of course, if you have questions or would like help, please reach out.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "GitHub Organization Search." @vsoch (blog), 14 Jun 2019, https://vsoch.github.io/2019/github-org-search/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).