Why do we need Laplace Smoothing?

| Let’s return to the problem of using Naive Bayes to classify a recipe as “ice cream”(1) or “sorbet” (2) based on the ingredients (x). When we are calculating our posterior probabilities, or the probability of each feature x given the class, we look to our training data to tell us how many recipes of a certain class have a particular ingredient p(xi | y=1) or p(xi | y=0). Let’s say that we are classifying a new recipe, and we come across a rather exotic ingredient, “thai curry.” When we go to our training data to calculate the posterior probabilities, we don’t have any recipes with this ingredient, and so the probability is zero. When we introduce a zero into our equation calculating the p(y=1 | x), we run into a problem: |

The capital pi symbol means that we are multiplying, so if it’s the case that just one of those values is zero… we wind up with 0 or NaN! Oh no! Abstractly, we can’t say that just because we have not observed an event (a feature, ingredient in this case) that it is completely impossible. This is why we need Laplace Smoothing.

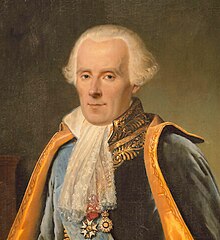

Why is this method called Laplace Smoothing?

You can probably guess that I’m about to tell you about a method that somehow deals with the very not ideal situation of having a posterior probability of zero. Why is it called Laplace Smoothing? This is the story, according to me, based on someone else telling me some time ago. There was this guy named Laplace who was pretty spiffy with mathematics and astronomy, and he thought about some pretty abstract stuff such as “What is the probability that the sun does not rise?” Now, if we were using Naive Bayes, we would of course calculate the posterior probabilities as follows:

p(x sun rises) = 1 p(x ~sun rises) = 0

Right? It has never been the case that the sun has not risen. We have no evidence of it! Laplace, however, realized that even if we have never observed this event, that doesn’t mean that it’s probability is truly zero. It might be something extremely tiny, and we should model it as such. How do we do that?

How do I “Laplace Smooth” my Data?

It’s very simple, so simple that I’ll just state it in words. To ensure that our posterior probabilities are never zero, we add 1 (+1) to the numerator, and we add k (+k) to the denominator, where k = the number of classes. So, in the case that we don’t have a particular ingredient in our training set, the posterior probability comes out to 1 / m + k instead of zero. Plugging this value into the product doesn’t kill our ability to make a prediction as plugging in a zero does. Applied to Naive Bayes with two classes (ice cream vs sorbet), our prediction equation (with k=2) now looks like this:

Thanks, Laplace… you da man!

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Laplace Smoothing." @vsoch (blog), 25 Jun 2013, https://vsoch.github.io/2013/laplace-smoothing/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).