The Flux Operator is a Kubernetes operator that makes it easy to deploy Flux Framework to Kubernetes. We did this by way of an Indexed Job that was running a replicated container with Flux alongside the application of interest. There is more detail about the design and features in this arXiv draft. This worked well for scaling MPI jobs, but had a huge design flaw.

The application logic was tangled with Flux.

This meant that application containers needed to be rebuilt to have Flux. And given the shared libraries on the system and various configuration files, we couldn’t wget a single binary (or similar) to add it to the container on the fly. This design flaw kept me up at night, for more nights than I care to remember. 😆️😭️

A Solution from the Metrics Operator

While designing the Metrics Operator, I stumbled on a design problem of a complex HPC application (HPCToolkit) needing to be added to a container on the fly that had the same problems as Flux - chonky in all the ways you could imagine. I found a creative solution, namely adding a sidecar container that would add an isolated Spack view to an empty shared volume, and then deem itself useless. The only compatibility to worry about would be the OS and version, and then (if relevant) things like PYTHONPATH or LD_LIBRARY_PATH. It not only worked for HPCToolkit, but I was also able to add Flux as an on demand “add on” to the Metrics Operator (detailed in the sidecar post linked above). I eventually distinguished two kinds of “containers I’d want to add on”:

- A sidecar container is needed if you need it to do something after the application runs

- An init container works for a software view that can be added and the provisioner removed

In simpler terms, if we can copy over a view (with some software to run) and then customize the application entrypoint to use it, the container doesn’t need to stay around and we can use init. If we need the same kind of interaction, but perhaps need to run some final steps, we can use a sidecar. I extended this learning to the oras-operator that serves as a namespace-based cache for workflow or experiment artifacts. It uses a sidecar, so ORAS (a command line client) can push the final artifact to the registry after the application finishes. Arguably, any sidecar (this one included) could also be an init container, given that the software in question installs to a view (and then has the matching architecture). In fact I might refactor this operator to use that approach, but I haven’t done that yet. But after figuring this out, the million dollar question was – could it be done for the Flux Operator too?

Absolutely! 🥳️

The Design

What has not changed

There are some salient design attributes that have not changed. First, our custom resource that the Flux Operator creates is called a MiniCluster. It is an indexed job so we can create N copies of the “same” base containers. While JobSet is an abstraction that I like (and we use for the ORAS and Metrics operators) I still don’t like that I have to install the extra manifests for it, and I also don’t love the longer hostnames. For these reasons (and not seeing so far a huge advantage to using JobSet) I have no fully ported to using it yet. The networking of the cluster is handled via a headless service, and configuration is done on the fly with a combination of entrypoint scripts and config maps (e.g., the curve certificate is generated by the operator using ZeroMQ and mounted via ConfigMap). The main broker pod (index 0) still runs flux start with a primary command, and the worker pods run flux start to bootstrap the cluster (MiniCluster).

What has changed

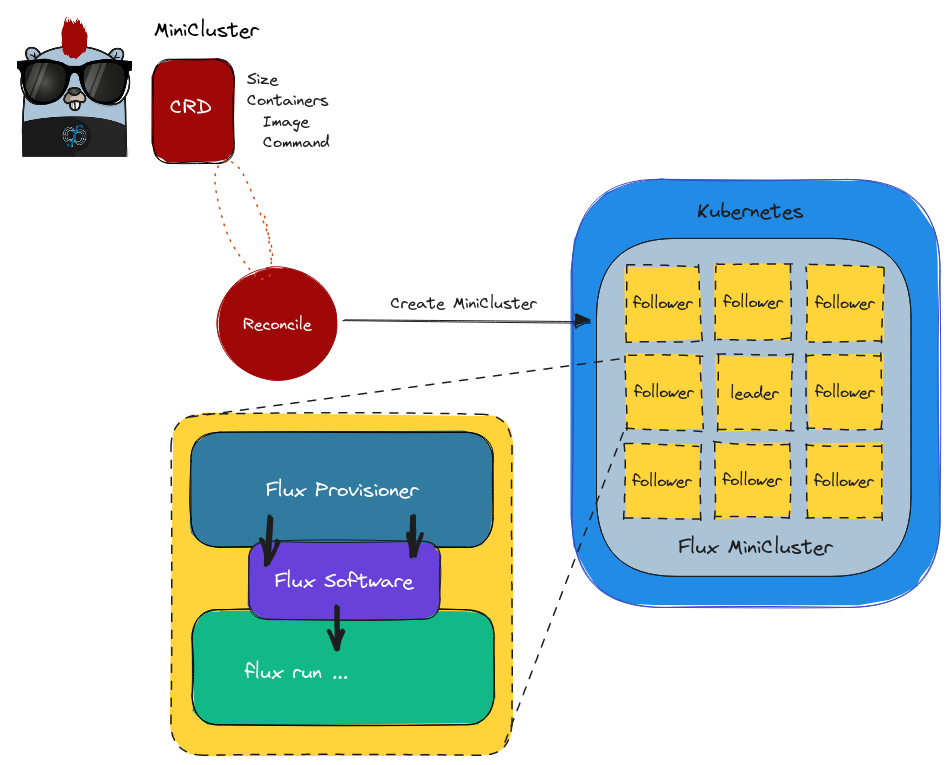

To handle the complexity of Flux, we now provide a set of Flux views, or containers that have Flux installed to a Spack view. We currently support Ubuntu (Debian) and Rocky Linux, and Alpine is (surprisingly) on the way since I started hacking on it this week with the Flux team (a lot of fun, and quite a rabbit hole)! This means that instead of requiring the application to be installed in a single container with Flux, we keep them separate. We call this flux view a “Flux Provisioner” and you can see how looks in the design below:

Let’s talk about how this works.

- The Flux Provisioner shares the view with the application container via an empty volume (purple)

- The provisioner (blue) is an init container, so it does setup and goes away

- Configuration is also done by the provisioner

- Multiple containers are still supported in your pod (e.g., your app + sidecar service)

- All sidecars still have access to run Flux

The last point is important, because it means that while some main application is running, we can interact with the (shared) broker socket and queue.

Sidecar Services for Flux?

I think there are several interesting use cases for sidecar containers that share access to the same Flux install and socket. The first might come when we can have more than one Metrics API endpoint. How might that work? Each Flux MiniCluster would serve its own endpoint, and the endpoint would be serving metrics from a sidecar container that can access the queue (and thus know the needs of that particular MiniCluster). This might work great for autoscaling. Another use case might be one container running the application, and a second submitting some-other-steps at various increments. It could also be used simply for monitoring. One thing I’m not sure about is the context of bursting. For a MiniCluster to burst it would need credentials to whatever place it is bursting to. This also means that you might have many MiniCluster each controlling separate bursts. But maybe an interesting idea would be to have a central scheduler orchestrating that, and issuing the command for it’s child MiniCluster to burst? 🤔️

Standalone Applications

Finally, as a final step to doing this transition, the original set of containers with Flux have (for the most part) been rebuilt to be containers that have the application without flux under rse-ops/flux-hpc. Not all of them are ported because I am being more selective (and have other things I want to do with the time). This was a lot of work, but I can’t tell you the relief to not have a gazillion builds of application + Flux to maintain. 😅️ But what I’m really happy about is:

If you have an application container that might be run with Flux on some HPC cluster, with the refactor you can try it with the Flux Operator, as is.

Thank goodness. Maybe I’ll sleep better now. Or maybe not. It’s hard being a dinosaur.

What has been removed

I often find when I’m designing software (from infrastructure to developer tools to applications or workflows) that I start out trying to implement a wide breadth of things. As I use it, or get feedback, I start to realize that some of those ventures are less likely to be used, or less important. I think it’s usually better to move forward making fewer features better than trying to maintain a larger set that you devote incrementally less time to. There were many examples of this for the Flux Operator, which I’ll briefly touch on.

Flux RESTFul API

For the first version, the Flux RESTFul API was built in, meaning that when you ran a cluster without a command (and not in interactive mode) you launched this service and could submit jobs to the cluster using it. As time went on, I didn’t like the tangling of these two things. For the refactor (TBA version 0.2.0), it is removed from being built into the operator, and instead provided as an example that can be run akin to any other. I like this approach better, because it simplifies the Flux Operator without removing a feature.

Multi-tenancy

Related to the RESTFul API was being able to use the Flux Operator with multi-tenancy. The more I’ve used Kubernetes and interacted with Kueue, I realized that putting users on the level of a single custom resource (MiniCluster) was likely the wrong place to put it. We can control permissions in Kubernetes via namespaces (e.g., RBAC) and it’s more likely that a single user is going to own an entire MiniCluster. Realizing this, I removed a bunch of extra logic from the Flux Operator that allowed defining extra users and adding them to the Flux RESTFul database. This also means we can run Flux in a single-user mode, and we do not need to generate a munge key. Finally, although flux is typically recommended to run as the flux user, given the challenges with storage (and managing the flux user vs whatever-user-is-in-the-container I fell back to even what I might consider a bad practice. We run everything as the root user. Might this eventually change? Definitely. But I don’t see the point of optimizing too early, and making life a lot harder (and the design more complex) when we are still in the stage of running experiments.

Storage Volumes

Holy hell, I did not know the pit of spikes and stinky socks I’d be jumping into when I first delved into Kubernetes (that has turned out to be volumes). I want to call it a hot mess, but I understand why it’s so complex - because it’s hard. The original design of the operator had volumes built in, meaning you could add variables to the custom resource definition (CRD) yaml file to help create or control persistent volumes and claims. I realized after many weeks of struggles that it would be a more sane approach to gut most of this out, and allow the user to specify existing volumes to give to an operator pod. This was a very satisfying deletion, and although we still need to deal with cloud-specific solutions, the good news is that the Flux Operator is much simpler. Moving forward (as I’ve already started to do) examples will be provided that show creating your own volume objects first.

Challenges I anticipate

So far, I have hit surprisingly few issues. The main issue I might hit is forgetting the OS that an application uses, and then seeing the error about GLIBC throwing up on me. The fix is to ask the flux container (the provisioner) to be different! That might look like this:

apiVersion: flux-framework.org/v1alpha2

kind: MiniCluster

metadata:

name: flux-sample

spec:

size: 4

flux:

container:

image: ghcr.io/converged-computing/flux-view-ubuntu:tag-jammy

containers:

- image: ghcr.io/rse-ops/laghos:tag-jammy

workingDir: /workflow/Laghos

command: ./laghos -p 0 -dim 2 -rs 3 -tf 0.75 -pa -vs 100

In the above, we ask to use an ubuntu jammy base (changing from the default Rocky Linux). I don’t know if I chose the “right” default (or if there is one) but this seems to work for now. The above is for running Laghos. The other issue that I anticipate will be more complicated given Python applications is just managing the PYTHONPATH and LD_LIBRARY_PATH. I haven’t hit many issues yet, but my experience tells me this is going to happen eventually, especially when we move into machine learning territory. We basically set everything up from mounted volume, and even provide a file to source (with some handy environment variables) for interacting with flux. As an example, after shelling into the container with a running Flux broker, you can connect as follows:

. /mnt/flux/flux-view.sh

flux proxy $fluxsocket bash

That said, there is no reason you can’t have your ML stuffs installed separately from where Flux is. Actually, I’ve done a few examples like that already (with mamba or conda environments) and it is what I’d recommend. And that’s it! That command (with a flux user and remembering where the socket is and setting the various envars) used to be so gnarly. It’s been much easier to develop with this design.

A Prediction

Given this early work I’ve done with operators, metrics, and workflow, I’d like to make a prediction.

A Kubernetes operator that can convert the logic of a workflow step into a batch object (e.g., Job, JobSet) and orchestrate and creatively customize it is going to be important for running workflows in Kubernetes.

I would extend that to say a workflow tool that can communicate with operators to submit jobs (e.g., Kueue) and orchestrate that running is another direction. Storage and saving the artifacts between steps is going to be hard (why I made the ORAS Operator - not a perfect solution but it’s going to make my life a lot easier for small experiments and workflow runs!)

I also predict we will see operators pop up that are for specific workflow tools, and (hopefully) have a large set to select from. The Metrics Operator is such a prototype, because it is based on capturing some set of variables to describe an application (that can thus be customized) with a container that has the needed software. We throw in tricks to use either init or sidecar containers to add “on the fly” functionality, and networking is creatively done with headless services (directly associated or not associated with the JobSet). You can easily imagine a workflow tool that supports running containers mapping the entirety of its representation of a DAG to such an operator. I haven’t delved into this approach yet because there are so many workflow tools, but it’s something I could easily imagine and design. What I’m thinking about now is a more simpler setup, one that uses Kueue to handle submitting jobs (and operator CRD that have underlying batch objects) to Kubernetes. Indeed, there are lots of ideas for this future vision of “workflows in Kubernetes” and I’m excited to see what others think of too.

Next Steps

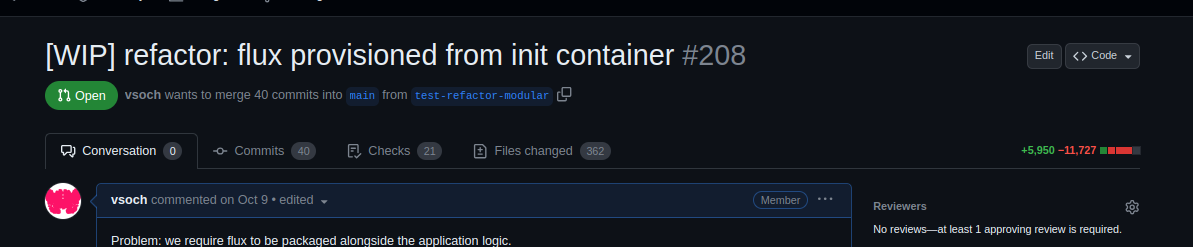

We are in the process of (about to submit) a paper on the Flux Operator, and notably we detail the first design. Thus, this second refactor is going to remain as a pull request to give us a chance to do some more scaled experimentation with it. If you are curious about the changes, here is the pull request. Here where I demonstrate using the ORAS Operator with the Metrics Operator to fully automate running LAMMPS, and mpitrace and hwloc alongside it to collect metrics. You basically create the artifact cache, run your script, and then (when it’s done) port-forward the registry and pull down all your artifact results. For the pull request, don’t let the numbers in the top right scare you…

Often to make things better (or different) we need to blow them up. I tend to develop like that, and I don’t have issue with completely changing my mind. And it feels like things have been busy with talks and conferences, but I’m hoping we can get back into more innovating work soon. The talks and conferences are fine, but the building part, and working with your team on that, is the best. ❤️

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "The Flux Operator Refactor." @vsoch (blog), 16 Nov 2023, https://vsoch.github.io/2023/flux-operator-refactor/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).