I was recently working on a new operator that I’m fairly excited about, the Metrics Operator when it so happened that I had an impossible situation - I wanted to use the metrics operator design with a shared process namespace to be able to monitor the application running in a Flux MiniCluster created by a different operator, the Flux Operator. Do you see where I’m going with this?

Oh nooo, but we can’t do that, Vanessa, because the Jobs with those containers are generated and owned by different controllers!

It’s not even an issue of ownership explicitly - the two containers that I needed stuck alongside one another in the same pod, and in the same Job, were in two separate Jobs, and one was a ReplicatedJob in a JobSet. It’s kind of like wanting to play card games with your best friend, but they are riding in a different car. So alas, it was not a design that would work out of the box. However, I had a really dumb idea that (after an experiment and a bit of development) turned into a much cooler idea, and one that can be generalized to what I’m calling “Kubernetes Operator Helpers!” Ah yes, you read the title of the post? Nice! 🍪️🥠️ Before we jump into that, just look at how cute this little tiger is - the logo or mascot for the Metrics Operator:

I created that through several derivations of an AI image generator, and actually did quite a bit of manual work in Gimp to clean it up and smooth it out The Metrics Operator is a new operator I’m working on in response to wanting to understand how things are performing in Kubernetes (storage IO, application performance) and not having a clue in hell. I will likely need to write a post just about this new operator at some point - he’s still 🚧️ under development! 🚧️

The Back Story - An Experiment

For some quick background, I had explored sharing process namespace between containers in a pod for the sole reason of application monitoring. I wanted some application container to be able to run, and to “sniff” it (via the shared process namespace) from another container. That design is written out in verbosity here and shown briefly below:

This worked great when my Metrics Operator was in control of deploying (and owning) both the application container and container that runs the metric of interest, sharing the process namespace. As an example, let’s look at a config, a metrics.yaml, that we would provide the metrics operator:

apiVersion: flux-framework.org/v1alpha1

kind: MetricSet

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: metricset

app.kubernetes.io/instance: metricset-sample

name: metricset-sample

spec:

application:

image: ghcr.io/rse-ops/vanilla-lammps:tag-latest

command: mpirun lmp -v x 1 -v y 1 -v z 1 -in in.reaxc.hns -nocite

metrics:

- name: perf-sysstat

The above will deploy an application container “ghcr.io/rse-ops/vanilla-lammps:tag-latest” that is slim in design in that it only has LAMMPS (a molecular dynamics simulator) and the dependencies for it.

A strength of the metrics operator is that you don’t need to build custom stuff into your application containers, a flaw in design I see with the Flux operator

The operator, via a JobSet, then kicks off a small problem size run of LAMMPS. The above is just a test case, which is why it’s so tiny. Given that we define the metric “perf-sysstat” (a known metric to the operator) this will create a sidecar container alongside LAMMPS, find the running process, and watch it with “whatever perf-sysstat does” (spoiler, it runs pidstat). This is a simple example because it deploys one pod with one metrics container (pidstat) and one LAMMPS container. This doesn’t reflect a real-world use case - LAMMPS is typically scaled across more than one node. But actually (without going into much detail) the operator handles this as well - if you add more pods to the spec, we will simply deploy that many, and each will have the performance of the LAMMPS run that it sees monitored. The takeaway from the example above is that regardless of the scale, we need those containers like two peas in a pod - one or more metrics containers need to be alongside the application container.

Monitor an application inside another operator?

But what happens when your application container is created by another operator, and in another Indexed Job entirely? To add the complexity, the Metrics Operator also uses JobSet so this was one big hairball. But I had an idea! Actually, what if we just dumped out the “guts” of the Flux Operator (meaning the config maps, the job, and the service and optionally volumes it created), and then grabbed just the pieces that we needed (mainly the config maps) and then allowed the Metrics Operator to control creation of the application container (running Flux) and the service?

An insight about operators

It was at this point that I had an insight about operator design. If you think about it, there are actually two cases of operator types:

- helicopter parent meaning that your objects warrant constant monitoring for updating. For this case, the operator needs to create, delete, and perform other update operations that would be challenging (or annoying) to do manually.

- 80s/90s parent they might drop you off at the birthday party, but you are on your own after that, and maybe even need to walk yourself home! For this case, the operator only exists to create and delete.

After you realize this distinction, you also realize that the second case - the more “I will make you and let you be” case is well-suited to be served by static YAML files. But I do want to stress that finding the second case backing an operator does not imply that the operator wasn’t necessary - a lot of the config generation could be manually arduous to do (as is the case with the Flux Operator) and you want it programmatically done. So for simple cases of using the Flux Operator (without scaling / elasticity), the operator is just a fancy, programmatic way to produce complex configs. This was the valuable insight that led me to the next conclusion:

Can I use the Flux Operator to just give me those said configs?

Manual dump of an operator

My first shot at this was entirely manual and a bit janky, but it totally worked! I had to create the MiniCluster that I wanted (from a minicluster.yaml custom resource definition), dump out the pieces to YAML, remove the ownership attributes (the owner being the Flux Operator) and then apply the config maps selectively to create. You can see the assets needed for that. I then was able to tell the Metrics Operator exactly how to create the Flux Operator application container (that uses said config maps) via this metrics.yaml. Side note - when I looked at all the original manifests) they really gave me an appreciation for the complex logic that the Flux Operator handles! I would never want to write that or update it or otherwise interact with it by hand.

And the good news is that although the above metrics.yaml is a bit complex than the average one I’ve written given all the volumes, aside from the command and image and working directory, this structure for a Flux MiniCluster never changes, so I’ll only need to write it once! Then I was able to create my Metrics Operator metrics set, where the application being monitored was LAMMPS being run by Flux. Super cool! But stepping back - it was manual work! I shouldn’t have needed to install the actual flux operator, apply the YAML to create it, dump out the configs, and then customize them. No, indeed not. There must be a better way…

Hey, I thought you said you’d talk about the Metrics Operator in another post?!

I’m sorry! I had to. I’m so excited about it. This is becoming a problem, isn’t it? Simmer down, dinosaur. Take a cold shower, or a nap.

Operator Helpers

This is where things felt obvious. I wanted my operator to have a set of helper commands, meaning commands that would be able to interact with or generate assets related to the Flux Operator, but without actually running the reconciler / controller. I wanted a helper to be a set of static binaries that would build alongside the operator, and be easily accessible also in the operator container, but via a different entrypoint. This was the adventure I had on my TODO list for last week, but actually only started yesterday evening. And even in this small bit of time when I worked on it, I learned a ton! After that huge background section, I’d like to share that learning with you today.

Review of the Design

For the design of the Flux Operator I had most of the Kubernetes object generation logic tangled with the reconciler. This was a design decision not particularly thought out, and mostly based on wanting to use the logger attached to the controller for debugging, and then make the association of the controller as the owner in the same function. That might look like this - here is an example of generating a config map, and having it bundled with an owner reference and reconciler.

// createConfigMap generates a config map with some kind of data

func (r *MiniClusterReconciler) createConfigMap(

cluster *api.MiniCluster,

configName string,

data map[string]string,

) *corev1.ConfigMap {

// Create the config map with respective data!

cm := &corev1.ConfigMap{

TypeMeta: metav1.TypeMeta{},

ObjectMeta: metav1.ObjectMeta{

Name: configName,

Namespace: cluster.Namespace,

},

Data: data,

}

// Log something with the controller logger

r.log.Info("ConfigMap", configName, data)

ctrl.SetControllerReference(cluster, cm, r.Scheme)

return cm

}

In the above, we see the controller reference being set, along with using the reconciler logger. These things don’t need to be provided in this function. We would have a more modular design to untangle these things, as follows:

// CreateConfigMap generates a config map with some kind of data

func CreateConfigMap(

cluster *api.MiniCluster,

configName string,

data map[string]string,

) *corev1.ConfigMap {

// Create the config map with respective data!

return &corev1.ConfigMap{

TypeMeta: metav1.TypeMeta{},

ObjectMeta: metav1.ObjectMeta{

Name: configName,

Namespace: cluster.Namespace,

},

Data: data,

}

}

And then set the owner reference / do logging from the calling function!

cm := CreateConfigMap(cluster, configMapName, data)

ctrl.SetControllerReference(cluster, cm, r.Scheme)

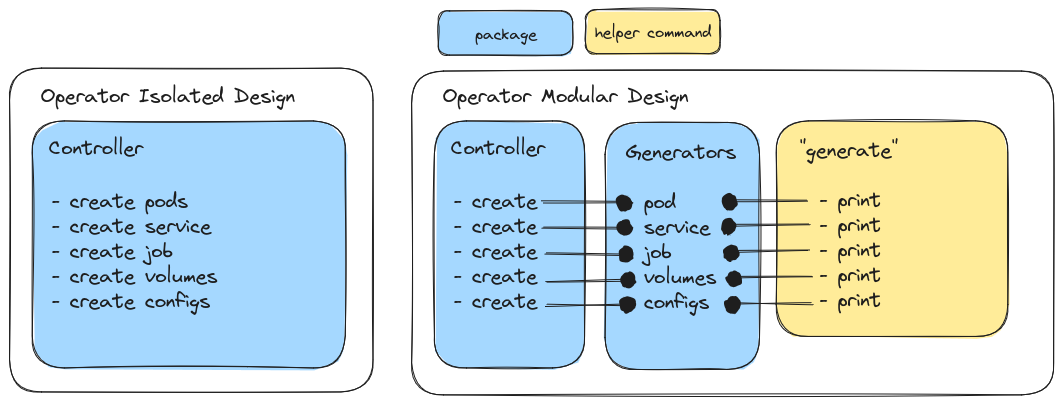

I hope the above is stupidly obvious. The second design affords more utility of your function, because it doesn’t bundle the generation with the controller, and require adding the owner. It also makes the function public (a capital letter) to be accessible outside of its package. When I realized this, I decided to do a small refactor of the Flux Operator to have this kind of design, because as I noted, we want to generate the various objects without relying on the controller running. And we most definitely don’t want to duplicate logic! Here is a quick diagram I put together to show the same idea above - the difference between a bundled vs. modular design.

The left is the quick and dirty design - everything, functionality, is packaged into the controller. Functions to create pods, service, job, volumes, config, etc. are one and the same with the functions that actually generate them in Kubernetes, and associate the controller. But what happens if you just want to get the objects (in Go) for something like linting or printing? This design breaks down. So then we look to the second design (right panel) where the basic functions to generate the assets are separate from the controller, and thus accessible by third party commands (yellow). Right now I still have these functions as publicly accessible from the controllers package, but I might change this in the future to be more explicitly modular. To be explicit:

Separation of concerns allows for exposing functionality that can then be run in different contexts, as the controller service or a static command.

You can look at the pull request for a more explicit show of the re-organization I did. I think eventually I’d like to create a separate “pkg” group that further separates the logic entirely. Likely I’ll want to make more helper commands in the future and this would be a good time.

Organization

My preference for organization is to put things where developers would expect to find them. The main binary generated for an operator builds to /manager in the container, and that is built from main.go in the root. However, for these helper commands, I took a standard approach and created a “cmd” directory:

cmd/

└── gen

└── gen.go

Gotchas!

There were a few things that over the course of the evening I had to figure out (and we can call them “gotchas!”.

Empty fields

When I first successfully printed a YAML structure to the terminal, of course using the default “yaml.Marshal” and then printing the string provided by Go, I was horrified to see the number of empty fields. At first I was trying to look up “how to hide empty fields from a struct when you don’t control the code” but that was largely a path that wouldn’t work. My insight was realizing that tools like kubectl don’t print an excess of empty fields, and then looking first here and ultimately here to understand how printing worked. The answer was ridiculously simple! There was a “sigs.k8s.io/yaml” library that seemed to handle this for me, and it subbed into “gopkg.in/yaml.v3” almost perfectly. My structures turned from monsters into something that looked more reasonable. The wisdom here, then, is that:

A nice strategy for “How do I do X” (given that you know someone has done X) is just to look at the code for X!

Often when it’s not the exact answer you want, you learn something or go down an interesting path anyway.

Type Meta

In my operator, I never bothered to define TypeMeta for an object. As an example to create a ConfigMap:

cm := &corev1.ConfigMap{

// Note this is empty, or it could be missing

TypeMeta: metav1.TypeMeta{},

ObjectMeta: metav1.ObjectMeta{

Name: configName,

Namespace: cluster.Namespace,

},

Data: data,

}

The assumption (I still presume) is that some component along the way can see that we are wanting a ConfigMap, and populate the default Kind and APIVersion (the two fields that go in there). But when I printed this to YAML? It looked like a mess - the fields were missing! So if this happens to you, you need to explicitly add it:

cm := &corev1.ConfigMap{

TypeMeta: metav1.TypeMeta{

Kind: "ConfigMap",

APIVersion: "v1",

},

ObjectMeta: metav1.ObjectMeta{

Name: configName,

Namespace: cluster.Namespace,

},

Data: data,

}

Runtime Schemas

When you look at enough operator code, when you see the main / startup logic, you usually see something like this:

import (

api "github.com/flux-framework/flux-operator/api/v1alpha1"

"k8s.io/apimachinery/pkg/runtime"

utilruntime "k8s.io/apimachinery/pkg/util/runtime"

)

var (

scheme = runtime.NewScheme()

)

func init() {

utilruntime.Must(api.AddToScheme(scheme))

}

That isn’t complete code, but what we see above is importing the API for our custom CRD (api) and creating a scheme with runtime.NewScheme() and then adding our api to it. There is a nice description of what this is doing here:

scheme defines methods for serializing and deserializing API objects, a type registry for converting group, version, and kind information to and from Go schemas, and mappings between Go schemas of different versions. A scheme is the foundation for a versioned API and versioned configuration over time.

So basically, we need to tell our code how to interact with our MiniCluster (the struct, specifically) and to serialize it to different formats. The gotcha here can be if you need other custom resources - you need to register them too! As an example, here is registering JobSet, which doesn’t come in the default set:

utilruntime.Must(jobset.AddToScheme(scheme))

Building

For building the helpers, I think it’s good to expose a Makefile command like “make helpers” to make it easy. But I also added it to my command to build the container, so “make build-container” will generate both. Since we do a multi-stage build, I ultimately copy the final fluxoperator-* commands to somewhere on the path, e.g.,:

COPY --from=builder /workspace/bin/fluxoperator-gen /usr/bin/fluxoperator-gen

So then this works:

$ docker run -it --entrypoint fluxoperator-gen ghcr.io/flux-framework/flux-operator:latest --help

Usage of fluxoperator-gen:

-f string

YAML filename to read it

-i string

Custom list of includes (csjv) for cm, svc, job, volume

-kubeconfig string

Paths to a kubeconfig. Only required if out-of-cluster.

And that’s really it - helper executables paired alongside the main operator manager (that starts the controller) that can be run more statically without bringing up the entire thing.

Include Preferences

I wanted an ability for the user to provide a single string with some order of letters that would say “generate the configs and job, but that’s it” so I came up with a (maybe silly) “IncludePreferences” struct that looks like this:

// IncludePreference keeps track of include preferences

type IncludePreference struct {

// By default, we generate all

GenVolumes bool

GenConfigs bool

GenService bool

GenJob bool

}

// determineIncludes determines what the user wants to print

func determineIncludes(includes string) IncludePreference {

// By default, we print all!

prefs := IncludePreference{true, true, true, true}

if includes == "" {

return prefs

}

// Volumes

if !strings.Contains(includes, "v") {

prefs.GenVolumes = false

}

// Config Maps

if !strings.Contains(includes, "c") {

prefs.GenConfigs = false

}

// Service

if !strings.Contains(includes, "s") {

prefs.GenService = false

}

// Job

if !strings.Contains(includes, "j") {

prefs.GenJob = false

}

return prefs

}

Then I could have an input argument (string) that takes some set of letters:

flag.StringVar(&includes, "i", "", "Custom list of includes (csjv) for cm, svc, job, volume")

And the person would use it like this:

# Only include the config maps

fluxoperator-gen -i c -f ./minicluster.yaml

Get the preferences from that string:

// Determine what the person wants to generate

prefs := determineIncludes(includes)

And then use it! My code would have blocks like this:

// Generate the MiniCluster assets (config maps and indexed job)

if prefs.GenConfigs {

cms, err := generateMiniClusterConfigs(cluster)

if err != nil {

l.Fatalf("Issue generating MiniCluster configs %s", err.Error())

}

for _, cm := range cms {

printYaml(cm)

}

}

Summary

TLDR: if you are interested in the new helper command for the Flux Operator, see here. I really like this generic design for operators, because it’s useful to provide associated tools that should not require bringing up the entire controller.

I wanted to share this because although it (in retrospect) seems simple, it’s not totally obvious when you have the idea and first are thinking about it. I pinged folks in the Kubernetes slack at some point last week to ask, and thanks to Bevan Arps for pointing me to asoctl. This is a supporting library to the Azure Service Operator, and I think the main difference is that it isn’t entirely decoupled from the running operator - I do believe that it expects to interact with one or more controllers. But conceptually, the idea of providing a helper binary alongside your operator is similar, and I appreciate his sharing with me!

To step back, I like this kind of work because it prompts us to think about package design. What goes in A vs. B? What should stay public vs. private? What is the best organization - should we put it where the developer expects to find it? Given said organization and design, how do we want to package the final outputs - separately or together? Does an additional component add an extra dependency or step that is not worth the addition? These are very basic development questions that we face from the first moment we make something that is greater than one script, but somehow after almost 15 years I still love the thinking space that comes with it.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Kubernetes Operator Helpers." @vsoch (blog), 19 Aug 2023, https://vsoch.github.io/2023/kubernetes-operator-helpers/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).