-

The Story of Stumbling

Almost eight years ago, the director of a group in a company where I worked gave me a book that changed my life. It was called Stumbling on Happiness, and almost eight years ago, I started reading it at my home in New Hampshire. I was terribly unhappy. I had gone through a highly painful and prolonged surgery at the end of the previous school year that, even after being released from the hospital after many weeks, left me with tubes coming out of my abdomen hooked up to a machine that I had to carry around in a black bag. Whomever made those tubes clearly was either just being practical, or had no empathy for a college student that would have to place the machine front and center on a desk in front of 160 other students. I also had experienced heartbreak, unfortunately at the exact same time, and that is on top of the normal introspective questioning about purpose, worth, and interacting with other people that is the albatross to any college-aged human. That was just the end of the school year. I launched right into a full time summer internship, which was physiologically stressful in that I made a 2-3 hour commute (one way) from New Hampshire to Boston each day. In a potpourri of transportation methods, it included driving, bus riding, walking, and sometimes a spurious trip on the T mostly because I like being in tunnels. However, the bus was my favorite because it was quiet and soft. I used to curl my knees up to my chest, plug headphones into the free music outlet, and quietly cry. This act, although embarrassing in most situations, is a well-needed release for emotion when there is no other cabinet to lock it into. Still, I did not show this to anyone, because to be so weak was so shameful. By the end of it all, specifically when it was time to return to school for another round, I went and came back. I had no drive to think hard about seemingly unimportant classwork because nothing was certain. I had always been a machine, and I was defined by strength and being able to survive things that are unexpected. But my foundation of certainty was about as substantial as bonito flakes. It would blow away whenever anyone sneezed.

I was laying on the floor of my room on a purple flowered rug that made me feel itchy, and despite the highly introverted nature of my family leading us to all be in our own sections of the house anyway, I had the door tightly shut. My room in our farm was over the section of the house without heat, away from the core of warmth from our wood stove, so it was always freezing. Since I was in college we had moved away from the house where we lived in high school, and I missed the soft carpet in my old room, and the warmth of the house. I’ve always been a floor worker, and a monkey in chairs, so I was appropriately sprawled out reading a book. In front of me was my Dell, my faithful companion, who currently had the World of Warcraft login screen open, showing my character, Sinotopia, standing at attention with a small movement every now and then to adjust a hand, wiggle a leg, or be convincing that she wasn’t actually a repeating animation sequence.

It was deep in the middle of the night, because I didn’t sleep so much, and I had just finished playing for many hours, and as I always did, I logged out and realized that the momentary distraction, the pixels that try to convince of meaningful interaction and accomplishment, did not serve to fill the emptiness that came to awareness after. It was my strategy to avoid spending quality time with myself, because I tend to think very critically about things, and go through a depth of introspection that is akin to diving shoulder-deep into the impressive pails that are hidden in the waist-high freezers at the ice cream shop where I worked in high school. I think about things a lot because I’m rather stupid. I can only understand things to any degree of satisfaction and reproducibility after tearing them into the tiniest of pieces, and then putting those pieces back together again. While getting the last scoop of ice cream would be desirable, this mental diving effort was something to be avoided. For this reason I had avoided (and still do, to some degree), extensive reading of things, or partaking in anything that wasn’t a straight forward, logical task. Anything other than enjoyable building or production of something, my brain would gobble up, and prompt introspection that was exhausting. It always (and still does) prompt me to write, because I have to put it somewhere to get rid of it. I was, possibly foolishly, reading Stumbling on Happiness.

It was deep in the middle of the night, because I didn’t sleep so much, and I had just finished playing for many hours, and as I always did, I logged out and realized that the momentary distraction, the pixels that try to convince of meaningful interaction and accomplishment, did not serve to fill the emptiness that came to awareness after. It was my strategy to avoid spending quality time with myself, because I tend to think very critically about things, and go through a depth of introspection that is akin to diving shoulder-deep into the impressive pails that are hidden in the waist-high freezers at the ice cream shop where I worked in high school. I think about things a lot because I’m rather stupid. I can only understand things to any degree of satisfaction and reproducibility after tearing them into the tiniest of pieces, and then putting those pieces back together again. While getting the last scoop of ice cream would be desirable, this mental diving effort was something to be avoided. For this reason I had avoided (and still do, to some degree), extensive reading of things, or partaking in anything that wasn’t a straight forward, logical task. Anything other than enjoyable building or production of something, my brain would gobble up, and prompt introspection that was exhausting. It always (and still does) prompt me to write, because I have to put it somewhere to get rid of it. I was, possibly foolishly, reading Stumbling on Happiness.  Yes, it’s no different right now, I went back to revisit that book. At the time I think that I was hoping that it would stumble me in the right direction, which appropriately, it seemed to do.

Yes, it’s no different right now, I went back to revisit that book. At the time I think that I was hoping that it would stumble me in the right direction, which appropriately, it seemed to do.It is typical for us to perceive experience, and color our experience based on context. The book’s charging message is that human beings are terrible at thinking about the future, specifically, we are hard-wired to be irrationally optimistic and be completely wrong about the things that will make us happy. Most of the book is filled with clever puns and an extensive reporting of every niche psychology study, ones that you could only imagine ways for how they got funding. At the time, I was overwhelmed with the realization that I didn’t know myself at all. I was no longer a competitive runner, something that had defined me for many years, I wasn’t particularly good at anything, and I was one of those unfortunate undergraduates majoring in computer games with a sampling of primarily useless Psychology courses on the side. I didn’t have many deep friendships because getting close to people meant vulnerability and being social was hard, and I was convinced of being the girl that could disappear and no one would (save possibly my parents) really notice. It’s a dangerous mental state, but I would suspect a common one, for the 20 year old with frontal lobes still developing. Although I was soaking in a marinade of computer games and self-loathing, what had always been my core, an embedded sense of logic and proactive decision making, was still with me. If I was unhappy, I just needed to figure out what would make me happy, and then do it. I needed time to think, and I knew that it wouldn’t happen if I felt trapped at a farm. I had always found inspiration from things that are beautiful, from movement, and from music, and so I decided to pursue those things. At approximately 5 in the morning in early September, I packed a small backpack with a cell phone, credit card, a Garmin navigation device, and one change of clothes, and decided to go for a really long run.

My plan was to go generally West, and I would use this time to think. This was the ultimate committment device, and relief from the situation of being trapped in a farm and the burden on my parents of dealing with my ornery self. I ran and walked for most of the first day, and by the evening I had covered over 40 miles, going from Weare to Keene, NH, and ending up at a hotel in some shopping center. My feet were bleeding. This was not something that I had expected. Matter of fact, I took a picture, if you can stomach it. It was then time to call my parents. I had decided to create some distance between us, because there was no way they would approve of this journey of mine. They still didn’t, but they have always approached raising my brother and I with an eternal provision of economic and functional support. They drove the distance (much faster than my much slower method) and they brought me my Brother’s old bike. I would bike for the remainder of the trip, with a short joy run in the morning to keep both muscle groups functioning properly.

Stumbling on Happiness changed my life because it prompted a journey from New Hampshire to Ohio, across tiny mountains that I wasn’t even aware of existing, and all the while asking myself a lot of hard questions that truly could only be addressed in the presence of rolling roadways, and the embrace of the wind.

I sometimes slept in actual hotels that surprisingly would offer immensely wonderful free food, cheap rooms, and encouragement, sometimes ad-hoc camp grounds, and one night was even privy to be in the same establishment of cabins as some kind of biker gang that did know how to have fun after the sun went down. The exhausting physical effort in the day, and sheer appreciation for things like warm showers gave me much needed moments of serenity and calm. I always woke up with the dawn, would put on my “other” change of clothes, and get back at it, namely, pedaling and thinking. After just under 1000 miles, going from New Hampshire through the majority of Ohio, I had regained my foundation of decision, meaning a set of proactive steps to take, a strategy, for resolving this current issue. I was resolved that my stubbornness had served me well before, and would do again, because it meant that I would never give up. I realized that It was acceptable to not have the answers, and to be stupid and lost, as long as there was a plan for moving forward. I had to also come to the acceptance that a chain of bad things had happened to me since I left high school, that it was unfortunate, that it had changed me irrevocably, and that I did not want to be defined by it. I also realized that the underlying sadness was prompted by an inability to foster any kind of control over my relationships, my future, or my incentive structure. However, control over those things is also (largely) an unrealistic thing to strive for. Rather, re-establishing happiness would likely involve re-building confidence, and a sense of control in having understanding of the tiny bits of experience that bring joy, and equivalently, stress and sadness. It was really a very selfish way of thinking, but mindless achievement followed by listless floor dwelling was simply not an option. What were those little things, and could I learn to incorporate more of the good bits into my life, and avoid the bad ones? It occurred to me that, while on the surface this goal was very selfish, I would be most useful and positively impact others given that I had a strong sense of self and purpose. I decided that the only way to figure out the things that would give me larger purpose was to dip my toe into many streams, and travel down many new roads.

I sometimes slept in actual hotels that surprisingly would offer immensely wonderful free food, cheap rooms, and encouragement, sometimes ad-hoc camp grounds, and one night was even privy to be in the same establishment of cabins as some kind of biker gang that did know how to have fun after the sun went down. The exhausting physical effort in the day, and sheer appreciation for things like warm showers gave me much needed moments of serenity and calm. I always woke up with the dawn, would put on my “other” change of clothes, and get back at it, namely, pedaling and thinking. After just under 1000 miles, going from New Hampshire through the majority of Ohio, I had regained my foundation of decision, meaning a set of proactive steps to take, a strategy, for resolving this current issue. I was resolved that my stubbornness had served me well before, and would do again, because it meant that I would never give up. I realized that It was acceptable to not have the answers, and to be stupid and lost, as long as there was a plan for moving forward. I had to also come to the acceptance that a chain of bad things had happened to me since I left high school, that it was unfortunate, that it had changed me irrevocably, and that I did not want to be defined by it. I also realized that the underlying sadness was prompted by an inability to foster any kind of control over my relationships, my future, or my incentive structure. However, control over those things is also (largely) an unrealistic thing to strive for. Rather, re-establishing happiness would likely involve re-building confidence, and a sense of control in having understanding of the tiny bits of experience that bring joy, and equivalently, stress and sadness. It was really a very selfish way of thinking, but mindless achievement followed by listless floor dwelling was simply not an option. What were those little things, and could I learn to incorporate more of the good bits into my life, and avoid the bad ones? It occurred to me that, while on the surface this goal was very selfish, I would be most useful and positively impact others given that I had a strong sense of self and purpose. I decided that the only way to figure out the things that would give me larger purpose was to dip my toe into many streams, and travel down many new roads.  I needed to try absolutely everything, and this filled me with a new sense of purpose and excitement. My appetite for risk was enhanced, and it retrospectively dawned on me that one of the hardest things in life, change, can sometimes only be spurred by an ability to embrace such risk. Further, uncertainty that may be deemed as risk at one point in life may completely lose the label when one has not much to lose. but much to gain.

I needed to try absolutely everything, and this filled me with a new sense of purpose and excitement. My appetite for risk was enhanced, and it retrospectively dawned on me that one of the hardest things in life, change, can sometimes only be spurred by an ability to embrace such risk. Further, uncertainty that may be deemed as risk at one point in life may completely lose the label when one has not much to lose. but much to gain.As quickly as I had left for the journey, I knew when it was over, and I was ready to go home. I found a local bike shop in a town I was passing through, a kid not much older than myself who put my bike in a box into the mail, and drove me to a tiny airport, asking nothing more than a $10 bill. I returned home just in time for my birthday, and my Dad, who was coming home from a long shift, brought me a blueberry muffin that we appropriately put a candle into.

On my 17th birthday, I was forced to grow up very quickly, and go through mental processes that likely don’t spawn into the end of the third decade of life. Although I was an old soul, my sense of self was not matched to that age. On my 21st birthday, as if both of us had been wandering the landscape for years, we drove up the same intersection, and were reunited.

On my 17th birthday, I was forced to grow up very quickly, and go through mental processes that likely don’t spawn into the end of the third decade of life. Although I was an old soul, my sense of self was not matched to that age. On my 21st birthday, as if both of us had been wandering the landscape for years, we drove up the same intersection, and were reunited.The Story of Stumbling: Coming Full Circle

It is now almost 8 years later, and while I take precautions to not return to things that bring subtle aches of memory, I realize that I need to come full circle in this Story of Stumbling. Reading some of this book for a second time has led to me thinking about the following points. The funny thing about these introspections is that I have seen many of these themes before, possibly hinting that I am rather slow at coming to resolutions, or limited in my own thinking capacity.

Emotional memory returns when prompted

In reading the pages of Stumbling on Happiness again, I was first overtaken with memory. There are aches of remembrance that I would much prefer to not feel again, and largely, I can control not feeling such aches by avoiding the experiences that cause them.

We vary in the degree to which we think about the future

I was next aware of a very basic assumption that the author was making – that people tend to think (or dream up) little fantasies of the future simply for pure enjoyment. This can be as simple as looking forward to a birthday party, seeing family, or having the weekend off. I know that I used to do that a lot, because I remember planning little parties, looking forward to showing a movie in Spanish class, or coming home for Christmas. I am very sensitive when I have epiphanies of being different, or possibly broken, and this realization made me feel that twinge. I think a lot about the present, most definitely the past to remember things that were enjoyable or funny, and while I cannot answer why I don’t fantasize about the future, I can say that it’s very infrequent. It does well to explain my fairly limited incentive structure to always be wanting to do things in the moment that give momentary fulfillment and purpose, and my traditional answer to “keep doing what I am doing now,” when asked about plans for the future. And so, I have come to realize that like most personality traits, people must differ in the degree to which they think about the future. I don’t have a sense for this distribution of people – it could be the case that chronically depressed dwell in the past (and are not privy to having the common irrational but evolutionarily advantageous optimistic life bias), and overly self-assured and economically gifted individuals live for dreaming up future scenarios to the point they assume themselves already there and have a very low tolerance for hard work or adversity. I just don’t know.

Context drives interpretation

I was next aware of the importance of context to drive interpretation. My first reading resulted in the thought “I have no idea about the experiences (functional, daily things) that give me meaning,” and for this second reading, the thought has changed to “I have no idea about the people (interactions) that give me meaning.” It’s easy to follow scripts based on previous social interactions to know what to do at a dinner outing, or an office meeting, but following such scripts is merely a strategy for being a functioning human, and says nothing about the good-feelingness (or bad-feelingness) that may come from the interaction. Arguably, if we make the assumption that humans are monogomous, long-term relationship desiring beings, we would strive to find relationships with others that maximize some benefit of each person to the other(s) life. It could be functional, emotional, physical, financial, or more realistically, some combination of those things. Eight years ago I was overwhelmed with needing to understand meaning in the context of myself, and now I am wanting to understand my meaning in the context of others.

We need one another

One of the deepest insecurities that can reside in a human soul is the fear of not having anything to add to anyone else’s life. Deep down, we all want to be needed and valued, by someone, for something, and possibly have some mental comfort that the strength of that need is substantial enough so that there is some certainty that it will endure. For even the tiniest thing, like taking head of the ship to bring someone else a coffee, being relied upon by a friend to bring a cherished snack, can well us up with happiness like bloated raisins. In fact, people like one another more when they ask for favors, but this stands in opposition to the common fear of inconveniencing people by asking for things. Asking for raisins, coffee, emotional support, or help is also context dependent. If an individual values another individual, the bond is strengthened. If the value is not yet established, the person is annoying, needy, and leads to the second individual not liking the person. This second situation is terrifying, and means that it is more risk averse to not ask for things. It’s also hard to ask for help because asking for help means being vulnerable. When we see things about ourselves that we do not like so much, given that we don’t like ourselves for having such things, it is only logical that others won’t either. On the other hand, knowing about others’ imperfections (counter-intuitively) makes us feel closer to them. The perception of an “average” or “generally normal” person is just that, a perception. Most people come from interesting life experiences, are survivors, and/or feel insecure about things, and the only true difference is the degree to which that information is revealed. For an individual with perfectionistic tendencies, the state I would call “self-loathing” comes strongly to mind. In absence of external support, that negative state is projected directly inward, and the projection of the underlying belief that led to the loathing onto others further prevents revealing such vulnerabilities to obtain support. This leads to an individual taking on the complete burden of their own insecurities, and what I would call existence at a distance. In this situation it is impossible to establish relationships where a duality of back and forth needing can be fostered, and thus the human desire for need is not fulfilled.

Choice paralyzes, and hinders connecting with others

To connect with others, it is essential to have some sense of self-worth. This is hindered because there is a tendency to immediately compare ourselves to some template or ideal, become aware of the enormous amount of choice that others have when choosing relationships, friendships, and conclude that it is minimally unlikely to be chosen over others. Even if we were to make the top of a list, it’s even more likely that people are terrible at allocating time, or even taking small actions to demonstrate to others that they value one another. To speak from personal experience, over the years I of course have had that insecurity, and while again there is no control over allocating others’ values, I have tried to make an effort to commit to things I know that I can make time for, and show value in the limited number of ways that I know how, which usually means being physically present, or giving presents (on a side note, nothing gives greater joy than presents, although ironically receiving them usually results in feeling badly that some amount of money or energy was spent).

Given that we are paralyzed by making choices, how do people connect with one another? What makes most sense to me is that people will naturally find one another when they like to do the same things (Oh, look, I choose to do X in my daily life, and you do too, we can do activity X together), when they also have affection for one another (Oh, you fell off your bike? I have this deep and confusing desire to take care of you), and when they don’t mind the other’s presence (Oh, it’s 9pm on a Tuesday night, yes I’m OK that you are breathing in the same space as me, and you will be occupying valuable blanket area in the same bed in about 20 minutes). It seems to me (and is unfortunate) that many relationships (whether romantic or friendship), get started based on convenience (or for just romantic, physical infatuation) and then the only logical result is that the individuals get bored of one another. Let’s be honest, even in “good” relationships this is highly likely to happen. It’s a terrible outcome because it really hurts to have this happen, and can negatively impact other wonderful things in daily life for many years. So, maintaining superficial relationships is a much safer strategy. But that means that we would be incapable of connecting with one another. What gives?

Being human probably means that we must try our hardest to connect, to be vulnerable, and know that any any moment it can all come crashing down. Reading some of these passages a second time, I am again thinking about my basic beliefs and the action that results (or doesn’t result) from them. As I get older, it occurs to me that there are times when I don’t want to have to be so strong. There are times when I really just want the biggest of hugs, or another human to have awareness of me needing support, even possibly when I do or cannot express it. On the flip side, an even deeper desire is to be the one that can give the support. What many of us ask, is that beyond friendships of convenience (like single serving airplane friends that will end when the flight is over) could there exist another person (robot?) that we might stumble into, and give insight to answering this question about what components of interaction provide deeper meaning? I suspect the answer to that question will be different for each person. I also suspect that answering it will require more risk taking and sheer luck, and finally having an answer will coincide with growing into a new level of interpersonal maturity.

The best strategy is probably maintaining openness to experience

I don’t know the answer to this question, and I’m not even sure how to figure it out. It’s pretty easy to address when introspection is involved. During my epic bike journey I thought over many experiences, and came to some basic conclusions that I needed to experience more things. In the case of people, other than going to a substantial number of social things, throwing away insecurity about talking to random people encountered in daily life, and in a romantic sense, going on an occasional date, there is no good way to “experience people.” Actually, the more salient factor here is control. With a search for meaning in the self, there is complete control over choosing experiences, deciding if they are liked, and then doing them. With people, even if the perfect other individual could be identified for a friend, housemate, or special life companion, there is no way to ensure that the liking would be mutual. It’s highly likely that it wouldn’t be. Most of the time some external life circumstances force interaction of people with one another, and further chance life circumstances, namely experiencing something that a second person also experiences, establishes special closeness. That makes it an even more impossible problem. Further, the common fear of vulnerability, tendency to not take risks, and easiness to let indecision guide decision (maintaining the status quot) means that answering this question has a large component that is chance. This subtly implies that there is no ideal strategy other than being open to experience, focusing on what gives meaning in the present, and letting probability do its thing. A third complicating factor is having an incentive structure that is not predictably average, and I am thinking of myself in this case. The first round of this “stumbling on happiness” introspection worked so well that I identified the little bits of things that gave me meaning, and now I find it hard to do anything else.

Conclusions

I again have many questions and not a lot of good answers. Ironically, I read about 2/3 of this book, got bored with the endless citations of “surprising” research, and still have not finished it. I suspect I will give it another try in 8 years! The problem is that, if we can break people into two groups: those that consume things, and those that produce them, my capacity for production of things far out-sprints my capacity to consume them. I don’t know how this is distributed in a normal population, but I’d guess given American culture that most are more heavy on the consumer side. In graduate school I have absorbed the belief that to be successful, I must err on the side of consumption with careful, targeted production. Thus, I live in constant angst that I am off balance, and try my every effort to resolve the weakness. But it could be the case that being highly proficient in both (living in autarky) is an inefficient strategy, and that the ideal collaboration would involve specialization, meaning the pairing of a consumer and a producer. The consumer would absorb all of the knowledge and need that is currently represented, and communicate what is missing to the producer, who would then fulfill the need. It’s a lot harder to ask good questions than to generate an algorithm or tool to answer them. I do need to find a good consumer, because I’m sure there are answers out there to some of my questions if internal drive to produce could be slowed down in favor of consumption. Perhaps I can only conclude that reading might be highly dangerous for me, because it results in something longer than the pages themselves.

On a more serious note, looking back on this experience, a proper conclusion to this 8 year introspection must include an evaluation. While sometimes it feels like it would be less of a burden to have the emotional depth of a goldfish, I find value in the possibility of being able to introspect, and instill change. While these early experiences (possibly) eliminated my capacity for deriving enjoyment from thinking about the future, they did alter my focus to direct, immediate actions and feelings, and over time that has instilled in me an almost stupid naivety and ability to derive joy from such trivial things. I plan my future in a way to maximize these momentary pleasures, which means avoiding airports, sitting in traffic, and post-office lines. It’s also lead to a (so far) bottomless well of motivation and drive that lacks any clear explanation for existing at all. When self-doubt and obstacles knock, while there may be a time when the turkeys get me down, a strength comes forth that transforms frustration into empowerment, and I try again.

One thing I am sure of, is that there are only about 3 hours left before I must bike home in the evening, and I really want to do some lovely producing! I don’t know if I’ll stumble into interpersonal meaning, but for now I’m going to stumble back into syntax colored gedit where I like to be :).

· -

Thinking About The Future

She used to climb the stairs in threes, and claim reward in the hot cup of coffee waiting for her lips in the small mail room by the flight. Half a mile from the building, the rich brown beans appeared in her mind’s eye, patiently waiting for the next academic to push the hollow, plastic black button. If she just went a little faster, those beans would belong to her. She could predict, and carry through with action to control her future, if just one sip at time. Life was many little games, just like these. There was infinite power in the threes.

But somewhere between her stoic bravery to survive that which was not meant to be, and an impenetrable heartbreak that catapulted her dimension of emotional experience five rainbows farther than one can perceive, she stopped thinking about the future. It existed in the expectations of others that were blurrily mapped onto her daily rituals, and appropriately perceived as life goals. It was unspoken and expected to want things in a year, two, or perhaps even three. But into that near, somewhat near, and approaching future, this girl did choose not to see.

They don’t talk about what it feels like to feel nothing at all, and to question the underpinnings of the human experience. They also don’t talk about the gift that results from such adversity, a selfish, wampant desire for constant, emotional feedback in the present. To wash the brain in the things that light it up is the ultimate ecstasy: akin to adding happiness bleach to make whites from a colorful wash cycle. It is choosing consistency over uncertainty. It is more alluring than any drug. She learned that heartbreak and predictable inconsistency are painful, and should be avoided at all costs.

He was her maybe. She never knew what it meant to have someone emotionally care for her, because in such perfect households to experience emotional roughing of feathers is to show weakness. Dually, she longed to be needed, for the opportunity to emotionally take care of someone. But to accept emotional support is to offer vulnerability, and reveal such shameful weakness. There was no room for weakness when she had to be strong. So it was always from within herself that she pulled strength, muffled away her vulnerabilities, and felt the overwhelming build up of everything that was not logic inside of her chest.

She found affirmation through music. It delivered the emotional validation from amygdala to prefrontal cortex that was undoubtedly matched to the color of feeling that she was experiencing at any moment. There are some things in life that are certain: creamrinse getting stuck in the top of the ear after a shower, things tasting better on the first bite, cars having faces if one looks closely enough, and the emotional salience of music. Music was the gentle stream that could invigorate and then wash away the things that were not logical inside her heart.

She searched for a love that would bring her peace. She kept such a fantasy in her mind, and so in most of the time when she was alone, that was all she might need. She searched for another that would reach between the cells and break the sheathing of perfection that cradled her heart. She searched for a love that made her feel free. But deep down, she understood what the naive, positive-thinking and biased average brain would typically rationalize away. The harsh reality was that people that she loved, or that might love her, eventually went away. There was only certainty in the hum of the self, and choices that were made for it, because this would endure as long as the heart beat and the mind remained sharp. And so this promise of a love was nothing more, could be nothing more, than a rosy, idealistic dream that served as an emotional blanket when the night felt a little cold.

The exception was in her dreams. The details of reality in the fabric of stories woven together by her subconscious were strangely more sharp than anything her eyes could see in the real world. If evolution and natural selection were still relevant, her extremely poor vision would have caused her to be eaten by a more important animal many years ago. But in the age of survival, when everyone who is broken can be fixed by metal rods and expensive procedures, she endured. And so in these dreams she found a strange sense of present in interactions and scenarios that could never be placed in time. It might have been her subconscious producing that which she needed so badly. In these dreams she found comfort, love, and richly bodied cups of coffee produced by impossibly perfect beans.

She used to climb the stairs in threes, until she realized there was more to appreciate in the current step than hope for what might be at the top of the flight. She was empowered in that moment, unstoppable and driven, and it no longer mattered what might be at the top of the stair. Indeed, thinking about the future is common, and can be alluring, but it just wasn’t for her anymore.

· -

I Can Change

the weeks cycled in eights toward those black and blue scars

such weakness sought sustenance in fish and packets of ghee

what cannot be seen in density sure must reveal in bars

the square plates were four but might as well been threethe end of one direction awaits a house setting by sun

power never does last when the shot does not be

legs behind wheels remembering the memory of the run

one if by laugh, two in note Cthe elegant cricket from the page questioning to be free

the machine learning clock hesiates in tandem to four

but now it is eight when these eyes are glazing to see

forever queue this name, forever | morethe lift is so cold, it does not go so high

surrounded by absence of everything but ground

searching for others, loneliness comes with a sigh

for that chilhood sundog, if only to be foundthe relief of an unexpected, catastrophic split

the hydrogel did split cleanly down to two

with grandpa draw-ties to happily sit

with no sharpness, the dress doesn’t have to be bluefloating on air, lovely those dreams

stay here forever there is not one but two

companionship found in the most unexpected way

take care of you forever I will most certainly doexhaustion is the border of beauty and fulfillment

stopping is the choice between devotion and me

when decision has no barrier to instillment

from this it can be found a driving to beI could not change but I certainly can

·

the gentle comfort of routine I will unravel

baby steps, a new and reasonable plan

from the inner locking of this mind, I travel -

Straws

nothing could reveal quite as much abut his flaws,

than the box of five hundred strawsgrab one to drink his water with ice,

and a stirrer for dissolving protein was also quite nice

the marginal cost of two

because there are countless others in view!

why should he worry about three?

when there are still hundreds of others to see!

but perhaps he will stop at four

because removing the wrapping is quite a chore

the upper limit is most definitely five

when there are still five times that alive

because to purchase such a thing anew,

was quite an easy thing to do.whittle away in impress it did

as there were no barriers placed on its lidakin to pulling just a little on a magic string

to decide what season to actually bring

when under the warm blanket of snow

he pulled a little for the promise of spring glow

when the buds were not quickly enough seen

a deliberate touch would make it green

and of course excitement of summer days

would end with his sweat beads of haze

because he was sure that the fall

truly had the wantings of it all

and so the seasons would high and low

never a friend, always a foe.he could not realize what he had done

until in his box there was only one

no more freedom to choose and date

this one left was his final fate

and so a deafening sadness he felt

to be playing the cards himself had dealt

but his despair was replaced with glee

a simple and clever solution, he could finally see

his ruthless consumption no longer a blur

his straw usage a well-defined, act of stiryou see, dear reader, the box never really was sparse

because insight to this future he could parse

it was when quite a plenty was left

that he saw his wasteful use as theft

each straw was not a faceless thing

but a promise of much happiness that it could bring!

if he took proper care of each of the bunch

he might never run out, was this clever hunch

and so life continued in this way

devotion to his straws he did not stray

and outlive the straws his time, he did

without the need for top, restraint, or lidnothing could reveal quite as much abut his flaws,

·

than the box of five hundred straws

but nothing could reveal quite as much about his soul

when living for each moment became his goal -

Visual explanation of coordinate-based meta-analysis approaches

Neuroscientists need to understand their results in the context of previous literature. If you spit out a brain statistical map from your software of choice, you might have any of the following questions:

- How consistent is the result?

- How specific are the brain regions(s) to the task?

- Does co-activation occur between… regions? studies?

Toward this goal, we have methods for “meta-analysis,” and for neuroimaging studies there are two types: coordinate (“peak”) based meta-analysis (CBMA) and image-based meta analysis (IBMA). The current neuroimaging result landscape is dominated by peaks, but now with growing databases of whole-brain maps we have entire mountains, and it’s this new interesting problem of needing to perform inference over these mountains.

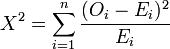

Recently I wanted to learn about meta-analysis approaches for coordinate data. I’ll be brief because I have much more I want to read, but I wanted to give a shout out to a figure (from a different paper) that really helped to solidify my understanding of the CBMA methods. I won’t re-iterate the methods themselves (please see the paper linked above), but they are broadly kernel density analysis (KDA), activation likelihood estimation (ALE) by way of GingerALE, and multi-level kernel density analysis (MKDA) that addresses some limitations of the first two (and don’t forget about NeuroSynth that mines these coordinates from papers and gives you tools to do meta-analysis!). This figure below comes from a paper by Salimi-Khorshidi et. al. that wanted to compare these common CBMA approaches to IBMA.

An illustration of ALE vs KDA vs MKDA (CBMA approaches) vs IBMA

I really appreciated this image for showing the differences between these CBMA (coordinate based meta analysis) approaches and then an image based meta analysis. I think that we are looking at method score/output on the x-axis, and voxels on the Y.

Each of first three rows contains a simulated dataset. The “true” signal is the dashed line, and then the bold lines in the first column of each row are that signal with added noise (imagine that there is some “true” signal underlying a cognitive experience that all three studies are measuring, and then we add different noise to that). The dots would be the “extracted peak coordinates” reported in some papers (and this is the data that would go into some CBMA). So each of the first three rows is a simulated study, and within those rows, the first column shows the “raw” data and “peaks,” and the last three columns are each of the CBMA approaches. In the last row, we see how the methods perform for meta-analysis across ALL the studies – however the very bottom left figure shows that the IBMA (averaging over the images) produces a signal that is closest to the original data, and this looks a lot better than the CBMA approaches (columns, 2,3,4). In summary:

- column 1: is the raw data, with the big black dots showing the local maxima that are reported, dotted line is “true” simulated signal, black thick line is that signal with added noise.

- column 2: shows the results of ALE: the result is more of a curve because the “ALE statistic” reflects a probability value that at least one peak is within r mm of each voxel, so the highest values of course correspond to actual peaks.

- column 3: kernel density analysis (KDA) gives us a value at each voxel that represent the number of peaks within r mm of that voxel. If we divide by voxel resolution we can turn that into a “density”

- column 4: is MULTI kernel density analysis, which is the same as KDA, but the procedure is done for each study. The resulting “contrast indicator maps” are either 1 (yes, there is a peak within r mm) or 0 (nope).

Please read the papers to get a much better explanation. I just wanted to document this figure, because I really liked it. The whole thing!

· -

The Velvet Stallion

Tangled and fiery, you know his kind

Intensity and anguish burns his mind

Darkly focused, inexorably lucid

Barraging loves, timidly elusive

The velvet stallion, charging by day

Barraging loves, barrier you away.A swirling of desire caught in his eye

Witty and fickle, but secretly shy

A single glance, you enveloped inside

A yearning of intense unforgiving stride

He dances the mountains, hoping for you

He clenches the wind, to hear what to doA parcel of dream new in his soul

Painful and tickle, confusing his goal

His passion is nausea, uneasy at best

His lucid dream, presenting without rest

The unrelenting yearning that brings a scar

The trickling wanting, to know where you areAtop of the world, heart racing with pain

The landscape he dominates, whispering a claim

It is not lust, sexual, or cognitively clear

why he shall never be rested without you near

Tamed he will not be, to pause in his stride

but to fit into your space, he shall abide.Tentative and cautious, proceed in your course

·

to have captured the spirit of this velveteen horse

His moment of clarity, in the quiet of his mind

he is infinitely connected to you, your subtle sign

A passion so wired, twisty, and deep

in his heart forever, you he will keep. -

T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

What do we want to do?

We want to visualize similarities in high dimensional data.

Why should we care?

We want to develop hypotheses about processes that generate our data, and discover interesting relationships. The visualization must match and preserve “important” relationships in the data without being too complex to be meaningless. Traditional methods like scatterplots or histograms only allow for the visualization of one or a few data variables at once.

Today

I want to learn about a particular dimensionality reduction algorithm that works very well with identifying patterns in large datasets, and integrates well into a visualization, t-SNE. I will talk about this algorithm in the context of brain maps.

Two levels of relationships we can capture

We need to capture relationships on two levels - a “local” or “high” dimensional one, and a “low dimensional” one, most commonly referred to as a “low dimensional embedding.”

Low-dimensional embedding:

For humans, distances between things are very intuitive to represent similarity Things that are closer together are more similar, and farther apart, more dissimilar. In this low dimensional embedding, we take advantage of this, and represent each highly complex brain map as perhaps a point on a flat plane, and it’s similarity to other brain maps is “embedded” in the distances.

Local relationships (high dimensional similarity assessment)

This refers to some algorithm that is producing a more complex assessment of how two brain images are similar. We can use any distance metric of our choice (or something else) to come up with a computational score to rank the similarity of the two images. This relationship between two points, or two brain maps, is a “local relationship,” or the “gold standard” that we aim to preserve in the “low dimensional embedding.”

Preserving local relationships in our embedding

Our challenge is to develop a low-dimensional embedding, a “reduction” of our data, that preserves the local relationships, which are the pairwise similarity assessments between each brain map point. This is challenging. Low dimensionality representations, by default, strip away this detail. However, there is a family of algorithms called “stochastic neighbor embedding” that aim to preserve these local relationships.

A distance matrix for each level

In machine learning, distance matrices are king. Each coordinate, I,j, represents a similarity between points I and j. In the context of our “low-dimensional embedding” and “local relationships” (gold standard), you can imagine having two distance matrices, each NxN, representing the pairwise similarities between points on these two levels. If we have done a really good job modeling our data in the reduced space, then the matrices should match.

Stochastic neighbor embedding

SNE is going to generate a distance matrix for each level, however we are not going to use a traditional distance metric. We are going to generate probability scores, where:for each pair of brain maps, a high score indicates that the two are very similar, and a low score, dissimilar. We are going to “learn” the “best” low-dimensional embedding by making the two matrices as similar as possible. This is the basis of the SNE approach.

- Stochastic: usually hints that probability is involved

- Neighbor: because we care about preserving the local relationships

- Embedding: because we are capturing the relationships in the reduction

T-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

We are minimizing divergence between two distributions:

- a distribution that measures pairwise similarities of the input objects

- a distribution that measures pairwise similarities of the corresponding low-dimensional points in the embedding

We need to define joint probabilities that measure the pairwise similarity between two objects. This is called Pij.

Here we are seeing the high dimensional space, and one of our brain maps (the red box), a point in the high dimensional space. We are going to measure similarities between points in such a way that we are only going to look at LOCAL similarities (we don’t care about the blue circles off to the left). We are going to CENTER a Gaussian at the red box, and this makes sense in the context of the equation because the numerator is the equation for a modified Gaussian (student-T distribution), and xi, the red box, is the mean (center). Then we are going to measure the “density” of ALL the other points under the Gaussian – this is represented in the part of the equation where we are subtracting the xj points. We can imagine if the other points have the EXACT same densities (if xi == xj), then we are left with a value of 0. If the distributions are more different, then this resulting density will be larger. The BOTTOM part of the fraction just re-normalizes the distribution in the context of all points in the space.

Probabilities to represent “gold standard” similarities

This gives us a set of probabilities, Pij, that measure similarities between pairs of points pi - a probability distribution over pairs of points, where the probability of picking a pair of points is proportional to their similarity. If two points are close together in the high dimensional (gold standard) space, we are going to have a large value. Two points that are dissimilar will have pij that is very small.

NOTE: In practice we don’t compute joint probabilities, but we compute conditional distributions (the top equation), and we only normalize over points that involve point xi (the denominator is different). We do this because it lets us set a different bandwidth, (the sigma guy) for each point, and we set it so the conditional distribution has a fixed “perplexity.

Perplexity (sigma) is adaptive to density fluctuations in our space

We are scaling the bandwidth (width) of the Gaussian such that a certain number of points are falling in the mode. We do this because different parts of the space have different densities, so we can adapt to those different densities.

We combine conditional probabilities to estimate the joint

We then say the JOINT probabilities are just going to be the “symmetrized” version of the two conditionals (the bottom equation in the picture above) - taking an average to get the “final” similarities in the high dimensional space. In summary, we now have a pairwise probability for each point in the high dimensional space.

We do the same thing in the low dimensional embedding

Now we are looking at the low dimensional space - whatever will be the final reduction - and we want to learn the best layout of points in that map. Remember that distance will represent similarity. Again, the red box is the same object, but now it’s in our low dimensional space. We center a kernel over our point, and then we measure the density of the other point (blue) under that distribution, and this gives us a probability Qij that gives us similarity of points in LOW dimensional space.

Remember!

- Pij : the high dimensional / actual / gold standard

- Qij: the reduction!

Pij should be the same as Qij!

We WANT the probabilities Qij (reduced) to reflect the probabilities Pij (high dimensional gold standard) as well as possible. If they are identical, then the structure of the maps are similar, and we have preserved structure in data. The way we measure the difference between the two is with Kullback Leibler Divergence, a standard or natural measure for the distance between two probability distributions:

Kullback Leibler Divergence will match our Pij and Qij

This is me reading the equation above. The Kullback Leibler Divergence for distributions P and Q is calculated as follows: We sum over all pairs of points, Pij, times log Pij divided by Qij. We want to lay out these points in low dimensional space such that KL divergence is minimized. So we do some flavor of gradient descent until KL divergence is minimized.

Why KL Divergence?

Why does that preserve local structure? If we have two similar points, they will have large Pij value. If that is the case, then they also should have a large Qij value. If they are exactly the same, then we take log of 1, and that is 0, and I don’t think we can minimize much more than that :). Now imagine if this isn’t the case - if we have a large Pij and a small Qij - in using KL divergence we will be dividing a huge number by a tiny one == huge number –> log of huge number approaches infinity –> the equation blows up (and remember we are trying to minimize it! So KL is good because it tries to model large Pij (similar high dimensional points) by large Qij.

What kind of Gaussian are we using?

When we compute Pij, we don’t use a Gaussian curve, we use student T-distribution with one degree of freedom. It’s more heavy tailed than gaussian. The explanation is that, if we were to have three points in the shape of an L, the “local” distances between points (the red lines) would be preserved if we flatted out the L:

However, the points not connected (the two gray on the end, the “global” structure) - their distance gets increased. This happens a lot with high dimensional data sets. By using the student T with heavy tails, the points aren’t modeled too far apart. I didn’t dig into this extensively, as I don’t find the visualization above completely intuitive to illustrating this difference between the two distributions.

Gradient of KL interpretation

The gradient with respect to a point (how do we have to move a single point in the map) in order to get a lower KL divergence takes the form in picture. It consists of a spring between a pair of points (F and C):

and the other term measures an exertion or compression of the spring:

Eg, if Pij == Qij that term would be zero, meaning no force in the spring! What the sum is doing is taking all forces that act on the point, and summing them up. All points exert a force on C, and we want to compute “resultant force” on C. This tells us HOW to move the point to get a lower KL divergence.

LIMITATION: We have to consider ALL pairwise interactions between points, need to sum in every gradient update. This is very limiting if we want to visualize datasets larger than 5000-10000 objects.

Barnes-Hut Approximation addresses computational Limitation!

The intuition is that if we have a bunch of points (ABC) that are close together that all exert a force on points (I) relatively far away, the forces will be very similar. SO we could take the center of mass of the three points, and compute the interaction between that point and the other point (I) and multiply it by 3 to get an approximation. Boom! This method comes from astronomy, and results in an NlogN algorithm.

In practice, the above is done with a “quadtree” - each node of tree corresponds to cell (eg, root is entire square map), and the children correspond to quadrants of the map. In each cell we store number of points in each cell, and the center of mass (blue circle).

We build a full quad tree - meaning we proceed until each cell contains a single data point. We do depth first search on the tree to do the Barnes approximation. We start with point F (in red), because we are interested in computing the interactions with this point:

At every point in our DFS, we want to know if the cell is far enough away from our point (F), and small enough, so that the cell could be used as a summary for the interactions. For example, below we are using the top left cell (the cluster to the left in the tree) - we calculate it’s center of mass (the purple circle) and calculate the interaction with F, and then multiply by 3 to account for points A,B,C. This is like a “summary” of the interaction of the three points on F. We then do this for all the points.

Extension to Brain Imaging Map Comparison?

This algorithm extends to multiple maps, and so I think it would be nicely extended to brain imaging to reflect different features (eg regional relationships) in our brain maps.

Credit for this content goes to Laurens van der Maaten, who is doing some incredibly awesome work that spans machine learning and visualization!

· -

My Definition of "Art" vs. "Something Else"

For years I’ve struggled with trying to define (for myself) the difference between “art,” and visualizations that (while of course they fit in the domain of art) I find inspiring or meaningful. I want to start with the understanding that yes, these things are rather subjective, and you are of course free to disagree with both my definitions and sentiments. This is an introspective, and personal post, and I do not intend to upset or spawn argument. I simply want to think through some of these ideas, and how they relate to academic research.

Skepticism of Stereotypical “Art”

The thing is, I really dislike experiencing most art. I usually don’t get it. Most of it is boring, and maximally it has some colors or shapes that are interesting or pleasing to the eye for a brief moment, but then it’s boring again. I know that “art” is a big part of human culture and has value for that, and in this light I’m probably just uncultured and ignorant. There are masterfully created, technically impressive works of art that catch my eye, however my appreciation does not extend beyond this superficial aesthetic. I largely don’t buy most assertions of claimed symbolism: if some kind of message isn’t clear from looking at the art alone, then the artist did not do a good job of communicating said message. If it’s not pleasing to my eye when I look at it, some underlying spiel from the artist isn’t going to suddenly transform the experience of the work for me. Creating something for someone that you care about is fundamentally different than creating something useful for society. Done.

I am conflicted because I love beautiful things. In my everyday life I am distracted by colors, lights, and natural beauty. I want to be at the top of a mountain when the sun rises, or discover patterns in the light peeking through the trees of a forest. Most “art” fails to capture these things for me, and in fact it bothers me when artists create some abstract thing that looks like squiggles and package in in some symbolic mumbo-jumbo that they claim to be profound. For me, “art” is a very personal practice of creating things that allow for personal expression in the same way as writing, or baking a cake for someone that you love. Going to “art school” has never made sense to me, because this personal drive and creativity has to come from within the person. Traditional school with grades and other incentives for learning makes sense in the context of obtaining skills that are essential for jobs in the traditional workforce. If an individual must use art school to support incentive for creating the art, he or she is going to be in trouble when that incentive stream comes to a close. Art school is also confusing because it places other artists in the role as “teachers” under some assumption that there is a “right way” to do things, but it’s totally subjective. If training in art is desired, the motivation must come from within, and when that motivation is present, the individual might naturally seek out other artists for learning and inspiration.

I am not suggesting that art does not have value. The practice of creation (or for some), experiencing something that is visually pleasing could add richness to an individual’s life, and this is again personal and subjective. It may be a shaky foundation to earn a living, however, if an individual wants to be an artist, that is a respectable aspiration. As I hinted at above, I do not think that such an individual would do best paying a tuition and going through the conveyor belt that has been defined in academia of doing thesis work, defending, etc. Most “art school” is a waste of time, and someone who is serious about creating things should just skip the formalities and devote every aspect of his or her being to doing just that – practicing, creating, and learning by doing. He should just put his money where his mouth is and prove that he can produce beautiful things, do it better, and attack the feat with unquestionable drive and passion to produce a substantial body of work. He should seek out others to learn from and collaborate with. With that level of intense focus he might successfully earn a living. And that will demonstrate that he is truly talented at his chosen craft so much more than some extension of letters to his name.

The “Doers”

This mindset extends beyond “art” – there is so much more in proactive “doing” than spitting out hot air about ideas. The ideas are actually ok, well more than ok – they are essential – given that they are interspersed with periods of “doing.” This “doing,” whether it be creating something visual, an algorithm, a piece of writing, or an analysis, is essential. I am so inspired by these “doers.” I am inspired by seeing people that put their heads down and stubbornly pursue building something until it goes to a state of completion. I’m inspired by people that come up with ideas, refine them, and then implement them. When challenge becomes exciting, and learning is craved, you can achieve this unbelievable mindset of not being afraid of failure. I want so badly to follow the lead of these doers, as I am also driven to make things. However, the context of these things having visual elements alongside my skepticism of art is something that I find very ironic. Sometimes I make a thing with the knowledge that it’s probably useless, but was fulfilling for me to make, or useful to learn something. My hope is that if I get good enough, I can master the elements and techniques of visualization to generate tools that add value to scientific discovery. I’m convinced that, if it’s done right, if it’s backed by data and has an actual use for society, then it becomes a completely different animal all together. And if the visual element is not up to par, I can hopefully sleep at night because the accompanying analysis was useful. And if neither of those things were useful, then I need to try again.

A Shift in my Research to Need Visualization

This drive to produce beautiful visual and meaningful things is a recent development when I realized that so much of data analysis could be aided and improved by simple visualization of the data. Something that is assumed to represent something may be completely off when you actually spend the time to properly visualize it. Something that has immense value that is not properly communicated to the broad scientific community may be entirely lost simply because people cannot see it. So when I realized two things, [1]: I was making assumptions about things in my data based on something trivial (extremely loaded in science is the p-value – it’s common to plug data into algorithms, get small p-values, and call it a day) and [2]: that I was not good enough to produce the visualizations that would be necessary to see these things, I came to the realization that visualization was essential to add to my toolbox as a researcher. I knew exactly what I wanted to produce, but I didn’t have the skills to make it. That seemed pretty lame. I don’t think an analysis without a meaningful visual communication of the findings will ever be enough for me anymore. I might have just shoved myself between a rock and a hard place, but it seems that there is enough time in life to get better at things.

Standards in Science

Is it a death sentence to set such high standards for work? Does it guarantee erring on the side of perishing? More importantly, could anyone ever really feel OK about pursuing publication of work that does not feel (gut-feeling wise) “good enough?” I could not. The work that we produce is a reflection of ourselves. I fundamentally believe that as scientists, artists, human beings, we must work so hard to be transparent, honest, and communicate our findings in the most unbiased way that is possible. Visualization can be essential toward this goal. There is also another, dark side that makes me terribly uncomfortable – the idea that because academic success is rooted in publication, it could be common practice to take some result and try to convince others of its value by inflating it with language. To take something that has not been properly pieced apart, visualized, and understood, and blindly try to convince others that it is sound seems like just another form of hucksterism. I think that good, solid science should almost stand on its own and require minimal additional convincing. In the light of “publish or perish” some kind of balance must be achieved. There is no way that we can be perfect, but we have to have some standard and just do our best. Learning to achieve this balance is part of graduate school and being a young scientist. We are all trying to figure out how we best fit into this larger academic and knowledge producing beast.

“Art” vs. “Something Else”

I was moved to write because I recently came across a talk by Santiago Ortiz that captured the “art” vs “scientific visualization” dilemma perfectly. He also moved me because of his sheer drive to learn and produce, independently, and under extreme pressure. I will try to summarize his main points:

“It’s not what it is, its where it operates. I want to work with people with real problems… and be part of the solution… I don’t want to create experimentalist stuff that ends up being presented as food for thought or inspiration etc. I wanted to work for clients with data… tools that enable people to explore, identify patterns, etc.”

And that hits the nail on the head for me. Meaningful visualizations solve problems. They may not be perfect, but they are backed by data and drive discovery and insight about some human behavior, biology, natural phenomena, etc. It is not enough to be someone that creates visual things, but it can be enough to be someone that creates tools to extend the human ability to understand the world. Santiago is inspiring because he brings to light (what I think) is an understanding that most “artists” choose to leave as an unconscious thought because scrutinizing their work for its true usability would be devastating. It may be impossible, but if in my lifetime I can contribute just one meaningful thing, and immensely enjoy the experience along the way, I think the time spent is worth it. The basis of my learning is informatics, machine learning, and brain imaging – we can call that the cake. The cake is a safety net, and the visualization a bonus, because we always have the cake to fall back on. However, if I can also contribute meaningfully with visualization, that means that I’ve baked a green cake with buttercream frosting, and chocolate bits, and from personal experience, I can attest that it is immensely fulfilling!

· -

Dynamic Rendering of Brain Atlas SVG for D3 Work

I was using traditional python tools to convert a brain atlas into an svg for use in a d3 visualization. Here is an example image (very pretty!)

But when you look at the svg data in a text editor, I ran into this horrific finding:

What you see is png image data being shoved into an svg image object, and they are calling that an “svg” file! What this means is that, although the format of the file is .svg, you can’t actually manipulate any of the paths, change colors, sizes, nada. It’s akin to giving someone a banana split made of plastic, and when they reach to pull the cherry off the top they discover in one horrific moment that it’s all one piece! Not acceptable. So I decided to roll my own (likely unnecessarily complicated) method together, and I learned a lot:

Making SVG Images for a Brain Atlas

It’s not that making an svg of a brain atlas slice is so hard, but if you want it to happen dynamically no matter what the atlas, then you can’t do tricks in Illustrator or Inkscape. The example above starts with a brain atlas image (a nifti file) and uses some basic image processing methods, including edge detection, segmentation, and drawing a line by walking along a distance path (I don’t remember what that’s called, I just made it up for the purpose) to end up with a proper svg file with paths for each region of the atlas. It’s also pretty cool because I used a library called Cairo to draw and render an svg, which is like a vector graphics API. Here is an example of one of my equivalent regions, this time represented as paths and not… clumps of misleading data!

Very cool!

· -

Backing Up Google Site

I keep my research wiki on a Google Site, and have been saving PDFs of the pages over the years as a backup. This seems like a pretty time intensive, and inefficient strategy. There is a nice tool called “google-data-liberation” that I’ve tried once or twice, also over the years, and never got it working. It occurred to me in a “acorn falling on my head from the sky” moment during my run this morning that… there is two step verification! /bonk. Of course that must be why it didn’t work in 2009… 2011… 2013… and all the other times I failed miserably to export my site! After 6 years of trying (ha) I finally got this to work:

Download the Application

Here. It’s a jar file. You need java. I have linux, so to run I do:

code

And that opens up a pretty little gui (I stole this from the main project page)

Generate a Two Factor Authentication Password

In your google account, go to Settings –> Accounts and Import –> Other Google Account settings and then go to “Connected Apps and Services” section. Click “View All.” First, revel in terror at the number of applications you’ve granted some tiny parcel of your personal information. Then go to the bottom and click manage app passwords. This will open up “App passwords,” and on the bottom is a big blue button to generate a new password, after you select a device (or custom). When you see the password, leave the window open.

Enter the correct information

Which is not in the example above! Let’s say your google site address is here:

http://sites.google.com/site/petrock

You would want to enter the following:

- Host: sites.google.com

- Domain: site

- Webspace: petrock

- Username: your full gmail (iloverocks@gmail.com)

- Password: the password you generated above

You also need to select a folder to export to, “target directory.” Make sure it’s a new folder, and not some place like your desktop, because a ton of files and folders are going to be generated. Then click “Export.” Then it actually works! I must say – 6 years of getting the “invalid credentials” bit… I’m glad I figured this out before I turn 30!

Now you can sleep at night knowing your graduate student drivelings are safely backed up, in the case that Google explodes. With all those rainbows coming from Mountain View, we just can’t be too sure what kind of mystery is going on behind tose red, blue, green, and marigold yellow doors! 😉

· -

Auditory Learning

I had an interesting experience today. I was concentrating heavily on removing the scaffolding from a 3d model. It fit nicely in the palm of my hand, and I was carefully prying off the waffle-like gray plastic away from the clean white model. Every little piece that came off was like the flake of one of those wafer cookies. If it weren’t obviously not delicious, I’m pretty sure I’d try to crumble them up and make a fudge-scaffolding bark.

While this was happening, my computer was playing hulu. It was a hospital documentary. Which one? It doesn’t matter so much, they are all the same. It’s what happens when you watch one thing, and then just let it keep playing: you get strange and mysterious shows that the hulu algorithms predict you would like based on your watch history, and the rest of the internet. Ok, here is the interesting thing. I’m definitely an auditory learner. If you can’t tell from my extremely dense writing style, I have affection for words, and I commonly think in metaphors. From when I was a little kid I noticed that when I heard someone speak, I would repeat all of the words in my head directly after they were said. I think probably everyone does this -it’s called listening :).

Today, the cool part was that I focused so intently on the task at hand, that the words from the show became the central thing in my mind’s eye. There wasn’t any visual to dominate the landscape. I then, subconsciously I suppose, started to visualize the entire thing. I didn’t just hear the characters speaking, I saw them walking in the hospital, the video camera zooming in on their faces, and the white shine of the coffee cup that clinked in the view. The very second that I realized what was happening, it ended. Right after the experience I was taken away by the coolness of it all. I have an extremely active, and vivid imagination, and I suppose I don’t give it a lot of time to do its thing without the context of sight. If I ever were to become blind, I would simply learn to see in my head, just like that.

It made me think though, could this be a tiny glimpse into how the brain can learn to pick up on other modalities? Does it help to explain why I dream so vividly? If we did an imaging study with individuals listening to a story, could we identify a cohort with significantly more activation in areas of visual cortex?

·

I’m not sure, but I am sure that I’m quite sleepy, and it’s time to give both parts of my brain a little fun time! I never know what I’m going to dream of, but it’s usually pretty good :). -

Spoons

Spoons are very special to me. I don’t know how it happened. It’s possibly because of the fact that it’s the only utensil I regularly use, and I typically have one special spoon that lasts for years and then breaks or gets lost (since graduate school I’ve gone through a hello kitty, a beauty and the beast, a scooby doo, and now a flowers spoon.) The hello kitty spoon broke in half. The beauty and the beast spoon I accidentally threw out, and realized this a day too late. I wish I could have rescued my spoon, but the trash truck had come. The scooby doo spoon was lost when I brought it to Asilomar this year (this is the price I pay for bringing my own, delicious peas!). For the ones that broke and I could say a proper goodbye to, I have documented their last days:

Tonight, my flowers spoon met the same fate.

I don’t think that this one was very old – I remember buying it at the Mollie Stones market, having it in my backpack, and showing to my friend Linda on campus. That was probably around my Quals time, which would be late 2013. The typical life-span of these plastic, dishwasher not-safe spoons is usually just a year. Think about the design. It’s plastic only barely fastened to a thin piece of metal, and the attachment is right at the point of force from the human hand. What typically happens is that a small piece of the plastic chips off first, allowing the metal to work as a lever just a little bit more with the force of the hand against the plastic, and then in one swift snap the entire thing cracks.

Why just one spoon? I don’t like to own a lot of things. I like the things that I do have to be carefully determined, and special (unless it is a gift, in which case I don’t have to do any thinking and it becomes by default a special item). If I am to use a spoon, it should be one spoon. It should be my absolute favorite. Sometimes that means biking all over the closest 3 towns, but when I find my new spoon, I just know! :)

More noticeable than the absence of the spoons, however, are the forks they leave behind:

It’s kind of like a sorry little box filled with lonely forks, just hoping that one day their special counterparts will come home safely. I feel so terrible. They have no idea! So the best I can do is just take care of them, safe and sound in their little magnetic box.

In honor of all my spoons, and for the many times I have used them as metaphors for different aspects of life, I want to share this poem I wrote in late 2012 about a particular, very tiny, very special spoon :O)

· -

The Graduate Student Avatar!