Why do we do research? Arguably, the products of academia are discoveries and ideas that further the human condition. We want to learn things about the world to satisfy human curiosity and need for innovation, but we also want to learn how to be happier, healthier, and generally maximize the goodness of life experience. For this reason, we give a parcel of our world’s resources to people with the sole purpose of producing research in a particular domain. We might call this work the academic product.

The Lifecycle of the Academic Product

Academic products typically turn into manuscripts. The manuscripts are published in journals, ideally the article has a few nice figures, and once in a while the author takes it upon him or herself to include a web portal with additional tools, or a code repository to reproduce the work. For most academic products, they aren’t so great, and they get a few reads and then join the pile of syntactical garbage that is a large portion of the internet. For another subset, however, the work is important. If it’s important and impressive, people might take notice. If it’s important but not so impressive, there is the terrible reality that these products go to the same infinite dumpster, but they don’t belong there. This is definitely an inefficiency, and let’s step back a second here and think about how we can do better. First, let’s break down these academic product things, and start with some basic questions:

- What is the core of an academic product?

- What does the ideal academic product look like?

- Why aren’t we achieving that?

What is the core of an academic product?

This is going to vary a bit, but for most of the work I’ve encountered, there is some substantial analysis that leads to a bunch of data files that should be synthesized. For example, you may run different processing steps for images on a cluster, or permutations of a statistical test, and then output some compiled thing to do drumroll your final test. Or maybe your final thing isn’t a test, but a model that you have shown can work with new data. And then you share that result. It probably can be simplified to this:

[A|data] --> [B|preprocessing and analysis] --> [C|model or result] --> [D|synthesize/visualize] --> [E|distribute]

We are moving A data (the behavior we have measured, the metrics we have collected, the images we have taken) through B preprocessing and analysis (some tube to handle noise, use statistical techniques to say intelligent things about it) to generate C (results or a model) that we must intelligently synthesize, meaning visualization or explanation (D) by way of story (ahem, manuscript) and this leads to E, some new knowledge that improves the human condition. This is the core of an academic product.

What does the ideal academic product look like?

In an ideal world, the above would be a freely flowing pipe. New data would enter the pipe that matches some criteria, and flow through preprocessing, analysis, a result, and then an updated understanding of our world. In the same way that we subscribe to social media feeds, academics and people alike could subscribe to hypothesis, and get an update when the status of the world changes. Now we move into idealistic thought that this (someday) could be a reality if we improve the way that we do science. The ideal academic product is a living thing. The scientist is both the technician and artist to come up with this pipeline, make a definition of what the input data looks like, and then provide it to the world.

The entirety of this pipeline can be modular, meaning running in containers that include all of the software and files necessary for the component of the analysis. For example, steps A(data) and B (preprocessing and analysis) are likely to happen in a high performance computing (HPC) environment, and you would want your data and analysis containers run at scale there. There is a lot of discussion going on about using local versus “cloud” resources, and I’ll just say that it doesn’t matter. Whether we are using a local cluster (e.g., SLURM) or in Google Cloud, these containers can run in both. Other scientists can also use these containers to reproduce your steps. I’ll point you to Singularity and follow us along at researchapps for a growing example of using containers for scientific compute, along with other things.

For the scope of this post, we are going to be talking about how to use containers for the middle to tail end of this pipeline. We’ve completed the part that needs to be run at scale, and now we have a model that we want to perhaps publish in a paper, and provide for others to run on their computer.

Web Servers in Singularity Containers

Given that we can readily digest things that are interactive or visual, and given that containers are well suited for including much more than a web server (e.g., software dependencies like Python or R to run an analysis or model that generates a web-based result) I realized that sometimes my beloved Github pages or a static web server aren’t enough for reproducibility. So this morning I had a rather silly idea. Why not run a webserver from inside of a Singularity container? Given the seamless nature of these things, it should work. It did work. I’ve started up a little repository https://github.com/vsoch/singularity-web of examples to get you started, just what I had time to do this afternoon. I’ll also go through the basics here.

How does it work?

The only pre-requisite is that you should install Singularity. Singularity is already available on just over 40 supercomputer centers all over the place. How is this working? We basically follow these steps:

- create a container

- add files and software to it

- tell it what to run

In our example here, at the end of the analysis pipeline we are interested in containing things that produce a web-based output. You could equally imagine using a container to run and produce something for a step before that. You could go old school and do this on a command by command basis, but I (personally) find it easiest to create a little build file to preserve my work, and this is why I’ve pushed this development for Singularity, and specifically for it to look a little bit “Dockery,” because that’s what people are used to. I’m also a big fan of bootstrapping Docker images, since there are ample around. If you want to bootstrap something else, please look at our folder of examples.

The Singularity Build file

The containers are built from a specification file called Singularity, which is just a stupid text file with different sections that you can throw around your computer. It has two parts: a header, and then sections (%runscript,%post). Actually there are a few more, mostly for more advanced usage that I don’t need here. Generally, it looks something like this:

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu:16.04

%runscript

exec /usr/bin/python "$@"

%post

apt-get update

apt-get -y install python

Let’s talk about what the above means.

The Header

The First line bootstrap says that we are going to bootstrap a docker image, specifically using the (From field) ubuntu:16.04. What the heck is bootstrapping? It means that I’m too lazy to start from scratch, so I’m going to start with something else as a template. Ubuntu is an operating system, instead of starting with nothing, we are going to dump that into the container and then add stuff to it. You could choose another distribution that you like, I just happen to like Debian.

%post

Post is the section where you put commands you want to run once to create your image. This includes:

- installation of software

- creation of files or folders

- moving data, files into the container image

- analysis things

The list is pretty obvious, but what about the last one, analysis things? Yes, let’s say that we had a script thing that we wanted to run just once to produce a result that would live in the container. In this case, we would have that thing run in %post, and then give some interactive access to the result via the %runscript. In the case that you want your image to be more like a function and run the analysis (for example, if you want your container to take input arguments, run something, and deliver a result), then this command should go in the %runscript.

%runscript

The %runscript is the thing executed when we run our container. For this example, we are having the container execute python, with whatever input arguments the user has provided (that’s what the weird $@ means). And note that the command exec basically hands the current running process to this python call.

But you said WEB servers in containers

Ah, yes! Let’s look at what a Singularity file would look like that runs a webserver, here is the first one I put together this afternoon:

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu:16.04

%runscript

cd /data

exec python3 -m http.server 9999

%post

mkdir /data

echo "<h2>Hello World!</h2>" >> /data/index.html

apt-get update

apt-get -y install python3

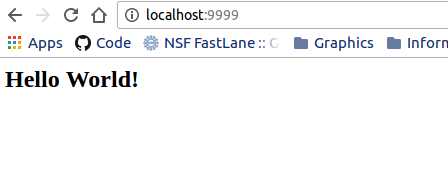

It’s very similar, except instead of exposing python, we are using python to run a local webserver, for whatever is in the /data folder inside of the container. For full details, see the nginx-basic example. We change directories to data, and then use python to start up a little server on port 9999 to serve that folder. Anything in that folder will then be available to our local machine on port 9999, meaning the address localhost:9999 or 127.0.0.1:9999.

Examples

nginx-basic

The nginx-basic example will walk you through what we just talked about, creating a container that serves static files, either within the container (files generated at time of build and served) or outside the container (files in a folder bound to the container at run time). What is crazy cool about this example is that I can serve files from inside of the container, perhaps produced at container generation or runtime (in this example, my container image is called nginx-basic.img, and by default it’s going to show me the index.html that I produced with the echo command in the %post section:

./nginx-basic.img

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 9999 ...

or I can bind a folder on my local computer with static web files (the . refers to the present working directory, and -B or --bind are the Singularity bind parameters) to my container and serve them the same!

singularity run -B .:/data nginx-basic.img

The general format is either:

singularity [run/shell] -B <src>:<dest> nginx-basic.img

singularity [run/shell] --bind <src>:<dest> nginx-basic.img

where <src> refers to the local directory, and <dest> is inside the container.

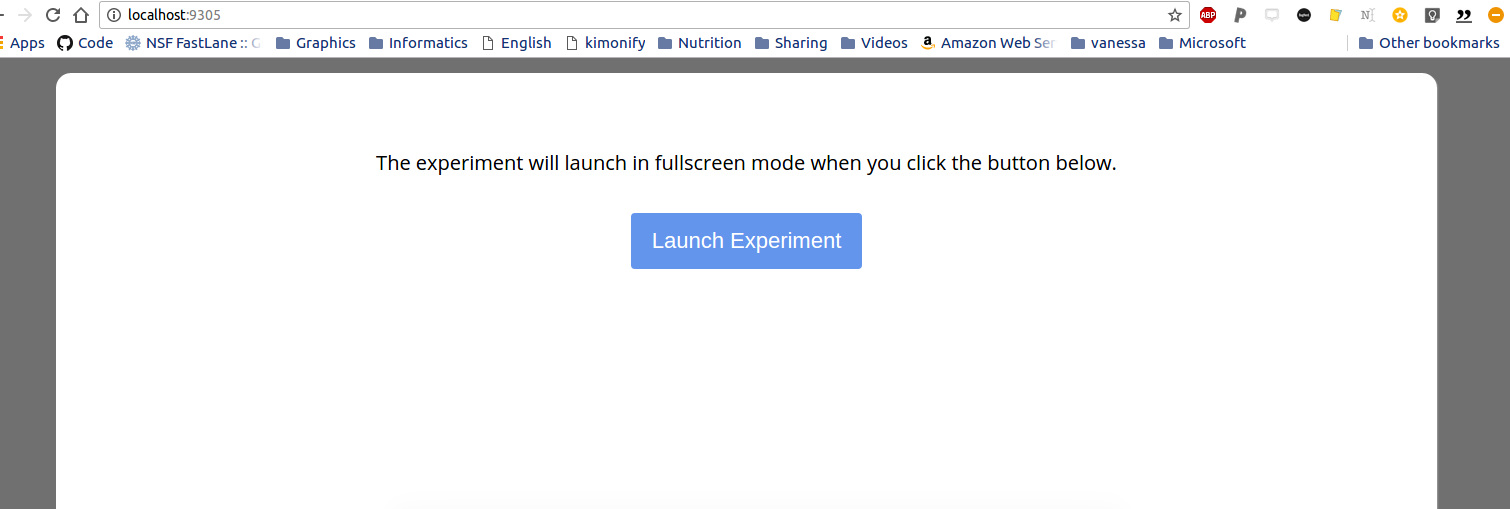

nginx-expfactory

The nginx-expfactory example takes a software that I published in graduate school and shows an example of how to wrap a bunch of dependencies in a container, and then allow the user to use it like a function with input arguments. This is a super common use case for science publication type things - you want to let someone run a model / analysis with custom inputs (whether data or parameters), meaning that the container needs to accept input arguments and optionally run / download / do something before presenting the result. This example shows how to build a container to serve the Experiment Factory software, and let the user execute the container to run a web-based experiment:

./expfactory stroop

No battery folder specified. Will pull latest battery from expfactory-battery repo

No experiments, games, or surveys folder specified. Will pull latest from expfactory-experiments repo

Generating custom battery selecting from experiments for maximum of 99999 minutes, please wait...

Found 57 valid experiments

Found 9 valid games

Preview experiment at localhost:9684

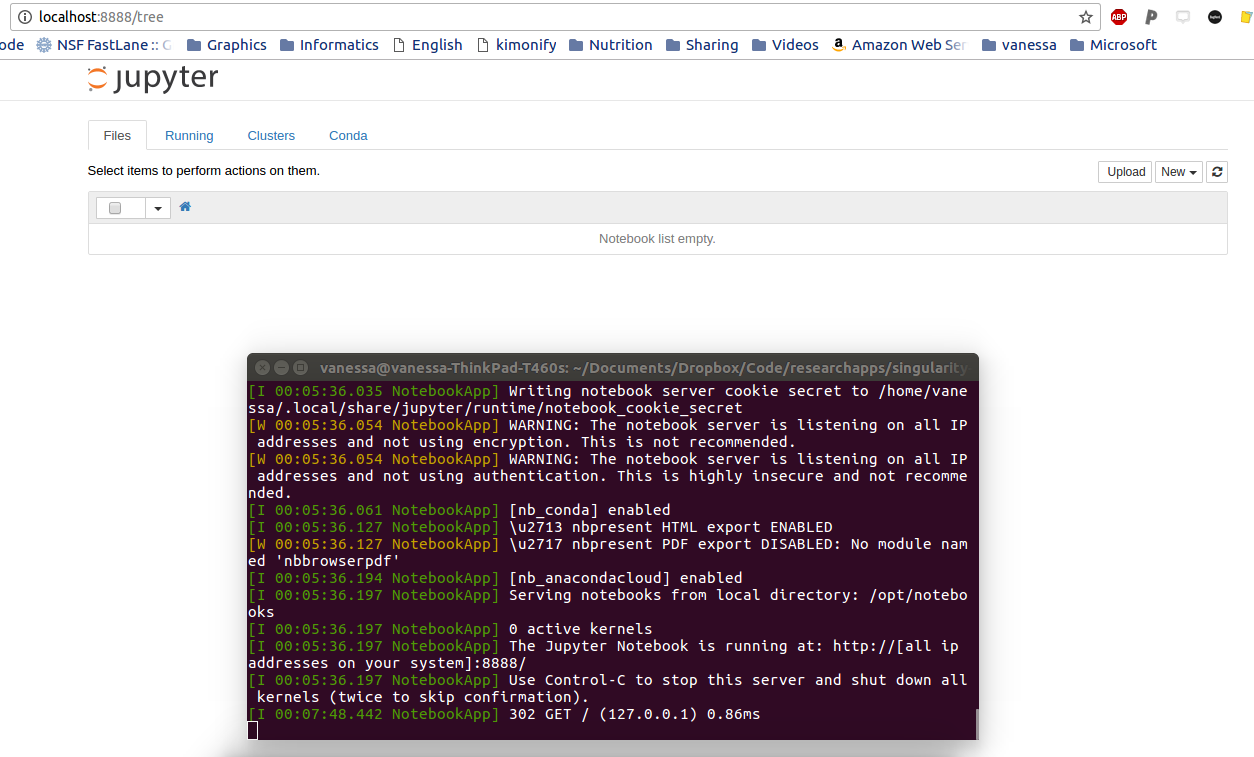

nginx-jupyter

Finally, nginx-jupyter fits nicely with the daily life of most academics and scientists that like to use Jupyter Notebooks. This example will show you how to put the entire Jupyter stuffs and python in a container, and then run it to start an interactive notebook in your browser:

The ridiculously cool thing in this example is that when you shut down the notebook, the notebook files are saved inside the container. If you want to share it? Just send over the entire thing! The other cool thing? If we run it this way:

sudo singularity run --writable jupyter.img

Then the notebooks are stored in the container at /opt/notebooks (or a location of your choice, if you edit the Singularity file). For example, here we are shelling into the container after shutting it down, and peeking. Are they there?

singularity shell jupyter.img

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity.jupyter.img> ls /opt/notebooks

Untitled.ipynb

Yes! And if we run it this way:

sudo singularity run -B $PWD:/opt/notebooks --writable jupyter.img

We get the same interactive notebook, but the files are plopping down into our present working directory $PWD, which you now have learned is mapped to /opt/notebooks via the bind command.

How do I share them?

Speaking of sharing these containers, how do you do it? You have a few options!

Share the image

If you want absolute reproducibility, meaning that the container that you built is set in stone, never to be changed, and you want to hand it to someone, have them install Singularity and send them your container. This means that you just build the container and give it to them. It might look something like this:

sudo singularity create theultimate.img

sudo singularity bootstrap theultimate.img Singularity

In the example above I am creating an image called theultimate.img and then building it from a specification file, Singularity. I would then give someone the image itself, and they would run it like an executable, which you can do in many ways:

singularity run theultimate.img

./theultimate.img

They could also shell into it to look around, with or without sudo to make changes (breaks reproducibility, your call, bro).

singularity shell theultimate.img

sudo singularity shell --writable theultimate.img

Share the build file Singularity

In the case that the image is too big to attach to an email, you can send the user the build file Singularity and he/she can run the same steps to build and run the image. Yeah, it’s not the exact same thing, but it’s captured most dependencies, and granted that you are using versioned packages and inputs, you should be pretty ok.

Singularity Hub

Also under development is a Singularity Hub that will automatically build images from the Singularity files upon pushes to connected Github repos. This will hopefully be offered to the larger community in the coming year, 2017.

Why aren’t we achieving this?

I’ll close with a few thoughts on our current situation. A lot of harshness has come down in the past few years on the scientific community, especially Psychology, for not practicing reproducible science. Having been a technical person and a researcher, my opinion is that it’s asking too much. I’m not saying that scientists should not be accountable for good practices. I’m saying that without good tools and software, doing these practices isn’t just hard, it’s really hard. Imagine if a doctor wasn’t just required to understand his specialty, but had to show up to the clinic and build his tools and exam room. Imagine if he also had to cook his lunch for the day. It’s funny to think about this, but this is sort of what we are asking of modern day scientists. They must not only be domain experts, manage labs and people, write papers, plead for money, but they also must learn how to code, make websites and interactive things, and be linux experts to run their analyses. And if they don’t? They probably won’t have a successful career. If they do? They probably still will have a hard time finding a job. So if you see a researcher or scientist this holiday season? Give him or her a hug. He or she has a challenging job, and is probably making a lot of sacrifices for the pursuit of knowledge and discovery.

I had a major epiphany during the final years of my graduate school that the domain of my research wasn’t terribly interesting, but rather, the problems wrapped around doing it were. This exact problem that I’ve articulated above - the fact that researchers are spread thin and not able to maximally focus on the problem at hand, is a problem that I find interesting, and I’ve decided to work on. The larger problem, that tools for researchers, because it’s not a domain that makes money, or that there is an entire layer of research software engineers missing from campuses across the globe, is also something that I care a lot about. Scientists would have a much easier time giving us data pipes if they were provided with infrastructure to generate them.

How to help?

If you use Singularity in your work, please comment here, contact me directly, or to researchapps@googlegroups.com so I can showcase your work! Please follow along with the open source community to develop Singularity, and if you are a scientist, please reach out to me if you need applications support.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Containers for Academic Products." @vsoch (blog), 27 Nov 2016, https://vsoch.github.io/2016/singularity-web/ (accessed 30 Sep 25).