Hierarchical clustering is a clustering algorithm that aims to create groups of observations or classes based on similar features, x. It is commonly used for microarray or genetic analysis to find similar patterns of expression, and I’m sure that you’ve seen its “tree” output in some paper (this tree is called a dendrogram).

Here we see experiments across the top, and genes down the side. By doing these two separate clusterings and then sorting in both dimensions, we can see patterns emerge in the data. This is a nice way to visualize patterns in data with many features.

Kinds of Hierarchical Clustering

There are two kinds of hierarchical clustering. Bottom up algorithms start with each data observation in its own cluster, and then sequentially merge (or agglomerate) the two most similar clusters until one giant cluster is reached. Top down algorithms start with all of the data in one giant cluster, and recursively split the clusters until singleton observations are reached. In both cases, you can then threshold the clustering at different levels (think of this like snipping the tree horizontally at a particular level) to determine a meaningful set of clusters. Agglomerative (bottom up) hierarchical clustering is much more common than divisive (top down), and will be the primary topic of this post.

Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (HAC)

Since we will be starting with singleton observations and merging (bottom up!), we need some criteria for assessing similar observations. Then, when we construct our tree, the y axis values will be our similarity metric, and we can start from the bottom and walk up the tree to reconstruct the history of merges. For most implementations of HAC, at each step we choose the best merge(s). A nice fact about this algorithm is that you don’t need to specify the number of clusters, as would be necessary in something like k-means. You can run the clustering, visualize the dendrogram, and then decide how to cut the tree. There are a few ways to decide on where to cut the tree:

- Cut at some threshold of similarity.

- Cut where the gap between two successive merges is the largest, because this arguably indicates a “natural” clustering.

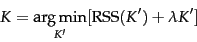

- Decide on a number of clusters, K, that minimizes the residual sum of squares. Specifically:

You can think of the second term as adding a penalty for each additional cluster, and this of course is based on the assumption that fewer clusters is better.

How is it commonly implemented?

Given N observations, the first step is to compute an NxN similarity matrix using your similarity criteria. You then go through iterations, and at each iteration, merge the two most similar clusters and update your similarity matrix with this merge. If we are doing single-link clustering then we assess the similarity of the closest observations in two clusters, and if we are doing complete-link clustering then we assess the similarity of the most dissimilar members of the two clusters. You can imagine that single-link will result in long, straggly clusters, while complete-link results in tighter clusters with smaller diameters. You could also do centroid clustering which evaluates the similarity of two clusters based on the distance of the centroids.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Hierarchical Clustering." @vsoch (blog), 06 Jul 2013, https://vsoch.github.io/2013/hierarchical-clustering/ (accessed 01 Jul 25).