Mutual information is an important concept for medical imaging, because it is so prominently used in image registration. Let’s set up a typical registration problem. Here we have two pictures of something that you see everyday, a dancing pickle!

I’ve done two things in creating these images. First I’ve applied a simple translation to our pickle, meaning that I’ve moved him down and right (a linear transformation), and I haven’t warped or stretched him in any way (a non-linear transformation). I’ve also changed his intensity values so that a bright pixel in one image does not correspond to a bright pixel in another image. Our goal, is to register these two images. Abstractly, registration is pretty simple. We need to find some function that measures the difference between two images, and then minimize it.

Registration with minimizing the sum of squared distances

The most basic approach would be to say “ok, I want to find the alignment that minimizes the sum of squared distances,” because when pickle one is lined up with pickle two, the pixels should be the same, and so our error is small, right? Wrong! This is not a good approach, because a high intensity in one image does not mean the same thing as a high intensity in the other. An example of this from medical imaging is with T1 and T2 images. A T1 image of a brain has shows cerebral spinal fluid as black, while a T2 image shows it as bright white. If we use an algorithm that finds a registration based on minimizing the summed squared distance between pixels, it wouldn’t work. I’ll try it anyway to prove it to you:

% Mutual Information

% This shows why mutual information is important for registration, more-so

% than another metric like the least sum of squares.

% First, let's read in two pickle images that we want to register

pickle1 = imread('pickle1.png');

pickle2 = imread('pickle2.png');

% Let's look at our lovely pickles, pre registration

figure(1); subplot(1,2,1); imshow(pickle1); title('Pre-registration')

subplot(1,2,2); imshow(pickle2);

% Matlab has a nice function, imregister, that we can configure to do the heavy lifting

template = pickle1; % fixed image

input = pickle2; % We will register pickle2 to pickle1

transformType = 'affine'; % Move it anyhow you please, Matlab.

% Matlab has a function to help us specify how we will optimize the

% registration. We actually are going to tell it to do 'monomodal' because

% this should give us the least sum of squared distances...

[optimizer, metric] = imregconfig('monomodal');

% Now let's look at what "metric" is:

metric =

registration.metric.MeanSquares

% Now let's look at the documentation in the script itself:

% A MeanSquares object describes a mean square error metric configuration

% that can be passed to the function imregister to solve image

% registration problems. The metric is an element-wise difference between

% two input images. The ideal value of the metric is zero.

% This is what we want! Let's do the registration:

moving_reg = imregister(input,template,transformType,optimizer,metric);

% And take a look at our output, compared to the image that we wanted to

% register to:

figure(2); subplot(1,2,1); imshow(template); title('Registration by Min. Mean Squared Error')

subplot(1,2,2); imshow(moving_reg);

Where did my pickle go??

Registration by Maximizing Mutual Information

We are going to make this work by not trying to minimize the total sum of squared error between pixel intensities, but rather by maximizing mutual information, or the extent to which knowing one image intensity tells us the other image intensity. This makes sense because in our pickle pictures, all of the black background pixels in the first correspond to white background pixels in the second. This mapping of the black background to the white background represents a consistent relationship across the image. If we know a pixel is black in one image, then we also know that the same pixel is white in the other.

In terms of probability, what we are talking about is the degree of dependence between our two images. Let’s call pickle one variable “A” and pickle two variable “B.”

If A and B are completely independent, then the probability of A and B (the joint probability, P(AB)) is going to be the same thing as multiplying their individual probabilities P(A)*P(B). We learned that in our introductory statistics class.

If A and B are completely dependent, then when we know A, we also know B, and so the joint probability, P(AB), is equal to the separate probabilities, P(AB) = P(A) = P(B).

If they are somewhere between dependent and independent, we fall somewhere between there, and perhaps knowing A can allow us to make a good guess about B, even if we aren’t perfect.

So perfect (high) mutual information means that the pixels in the image are highly dependent on one another, or there is some consistent relationship between the pixels so that we can very accurately predict one from the other. Since we have the raw images we know the individual probability distributions P(A) and P(B), and so we can measure how far away P(AB) is from P(A)P(B) to assess this level of dependence. If the distance between P(AB) and P(A)P(B) is very large, then we can infer that A and B are somewhat dependent. More on this computation later - let’s take a look at mutual information in action.

% Now let's select "multimodal" and retry the registration. This will use

% mutual information.

[optimizer, metric] = imregconfig('multimodal');

MattesMutualInformation Mutual information metric configuration object

A MutualInformation object describes a mutual information metric

configuration that can be passed to the function imregister to solve

image registration problems.

% Now the metric is mutual information! Matlab, you are so smart!

moving_reg = imregister(input,template,transformType,optimizer,metric);

% Let's take one last look...

figure(3); subplot(1,2,1); imshow(template); title('Registration by Max. Mutual Information')

subplot(1,2,2); imshow(moving_reg);

Hooray! Success!

Mutual Information - the Math Behind It!

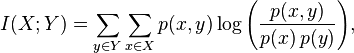

We’ve shown that mutual information is the way to go to register two images with different intensity values (i.e., different modalities). Here is the actual equation to measure mutual information (this is the value that we would iteratively try to maximize)

This is for discrete distributions, and if we had continuous distributions the summations would turn to integrals, and we would add dxdy to the end. Given that we are summing probabilities, this value always has to be positive. Can you see what happens when our variables are completely independent, when p(x)*p(y) = p(x,y)? We take a log of 1, and since that is 0, our mutual information is also 0. This tells us that knowing A says nothing about B.

Kullback-Leibler Divergence - Another measure for comparison

| KL Divergence is another way to assess the difference between two probability distributions. It’s even special enough to have it’s own format, specifically if you see DKL(A | B) those symbols mean “the kullback leibler divergence between variables A and B.” In real applications of KL, the value A usually represents some true distribution of something, and B is how we model it, and so DKL(A | B) is getting at the amount of information lost when we use our model, B to guess the reality, A. Here comes the math! (thanks wikipedia!) |

The above reads, “the KL divergence between some real distribution, P, and our model of it, Q, is the expectation of the logarithmic difference (remember that a fraction in a log can be rewritten as log(top) - log(bottom)) between the probabilities P and Q, where the expectation is taken using the probabilities P.” Again, when our model (Q) fits the reality well, (P) ad the two probabilities are equal, we take the ln(1) = 0, and so we would say that “zero information is lost when we use Q to model P.”

The above code is also available as a gist here.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Mutual Information for Image Registration." @vsoch (blog), 03 Aug 2013, https://vsoch.github.io/2013/mutual-information-for-image-registration/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).