Nobody ever goes in… and nobody ever comes out.

I’m excited to share more progress on the now beta version of The Experiment Factory, with the following updates:

- support for postgresql, sqlite, and mysql in addition to the default filesystem

- tutorials for each database, and for accessing data

- a browsable, tested library and API

- the library includes 95 experiments (jspsych paradigms, phaser games, and traditional surveys)

- an experiment container builder

- a survey generator container to turn a single tab separated file into a web-ready survey.

This means that it is easy for a researcher to contribute in many ways, or just use the tool! If you want to jump in and try some experiments for yourself, here is the “quick start”

docker run -p 80:80 vanessa/expfactory-surveys start

docker run -p 80:80 vanessa/expfactory-games start

docker run -p 80:80 vanessa/expfactory-experiments start

and then open your browser to 127.0.0.1. You can also see a listing of all our experiments:

docker run vanessa/expfactory-builder list

For this post, I will review history of the Experiment Factory, followed by problems that the new version solves. If you just want to see pictures, jump down to a quick look.

Experiment Factory History

The initial work was founded on the observation that it was really hard for psychology labs to collect behavioral data, and this data is one of the cores to doing research. I worked or was part of several labs between college and graduate school, and although some used more scaled methods (e.g. Amazon Mechanical Turk), a large portion would do the old-school “bring participants in and sit them at a computer” sort of deal. At Duke we ran the Duke NeuroGenetics Study, and I implemented a multi-hour long assessment of surveys with Qualtrics in a small computer lab ( here I am as a small Vanessasaur dancing around). It was a lot of detailed and tenuous work, and the extent of the behavioral tasks we had were on USB sticks or run with old software called e-prime at the scanner. When I started to notice that it was always done from scratch, and labs didn’t like sharing their work, it made no sense. When I came to Stanford and saw a colleague making beautiful experiments that were hard coded (and thus hard to extend in other ways) we worked together to create the initial release of the Experiment Factory, which was primarily a set of web based experiments driven by a Python tool and (a closed off) expfactory.org. It was the most fun and fulfilling experience I had during my graduate career - I was doing the part that I loved (software engineering) but working together with my lab mates toward a common goal. The fact that we couldn’t open up the served version introduced me to new (and very real) challenges to providing software as a service. If data is involved that means liability and responsibility, and small labs have to deal with enough as it is.

It Wasn’t Good Enough

I was contented at the time that users could harnass the python software to generate local batteries, and more advanced users could set up the Docker image to run paradigms on Mechanical Turk. I also had graduated and needed to, you know, do other work. However, as a handful of years went by, I noticed the following (major) issues:

Problems

- dependencies the python base, given installation on a new host, was prime to break, usually due to different versions of modules or other dependencies

- scaling the experiment library was too big. Testing or adding a single experiment meant cloning the entire library, meaning all images and associated static file for every experiment. It also was a bad model for ownership - a user should be able to maintain his or her own experiment repository and submit it to the library. My lab at some point turned off testing entirely, which was probably their only option given how long some of the experiments took for the robot to complete.

Solutions

- expfactory software: is now provided, ready to go, within a container. You don’t need to worry about installing it on your host. Containers are provided for building a custom experiments container, or generating a surveys repository from a tab delimited file.

- experiments are truly modular in that each is in it’s own repository. This means distinct permissions (owners), tests, and an issue with a single experiment can be dealt with in isolation from the others.

- the library: is a tested resource that experiments are contributed via Pull Request. How does it work? You add a single text file, and it automatically tests your experiment repository, and merge updates the API and web interfaces. Yes, I’m lazy, and I want this to all happen for me.

Reproducible Paradigms

Once you build your experiment container and provide it’s unique identifier in a registry like Docker Hub, you can cite it in a paper and have confidence that others can run and reproduce your work simply by using it. This is the benefit to container technology like Docker - the dependencies and particular configuration of your work are frozen. You can:

- generate a container to serve experiments, and include it in a publication for others to use to reproduce the work

- collaborate on experiments together via Github issue boards, pull requests, etc.

- capture changes to any standard experiment via commands in your build recipe

A Quick View

If you want a thorough walk-through of using the containers or building an experiment, see our official documentation. This will be a broad overview with some pictures of the interface. First we start with a container from Docker Hub

docker run -p 80:80 vanessa/expfactory-experiments start

Then we open our browser to 127.0.0.1.

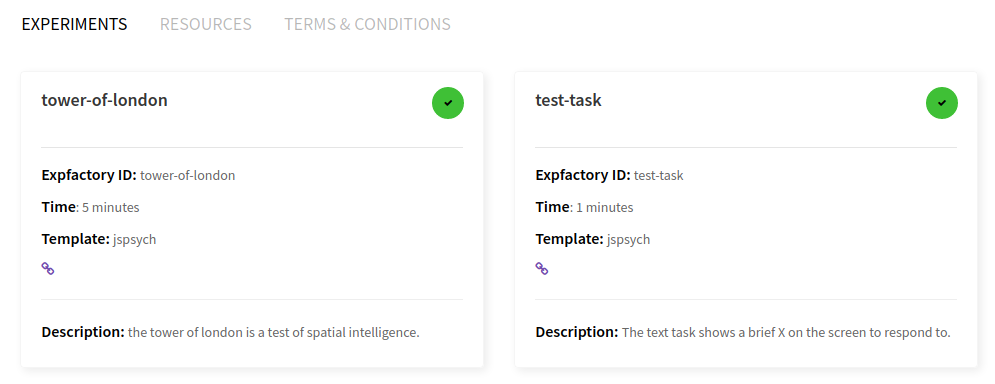

This is where the experiment administrator would select one or more experiments, either with the single large checkbox (to select all) or smaller individual checkboxes. When you make a selection, the estimated time and exeperiment count on the bottom of the page are adjusted. Here we see selection of test-task and tower-of-london (my favorite). I would recommend the test-task as a first try, because it finishes quickly.

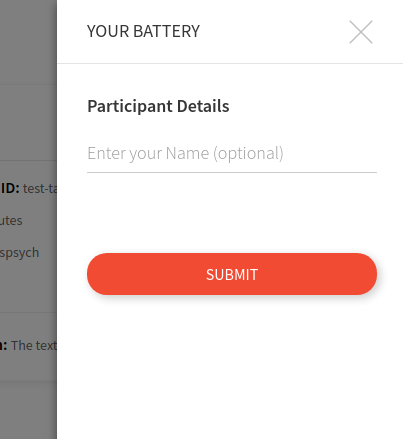

Once you make a selection, clicking “Proceed” will show the panel below to start the session. When you click on proceed you can (optionally) enter a participant name. Note that this panel is mostly useless, because nothing is saved, but intentionally placed to allow future support for other means to log in or provide participant inputs.

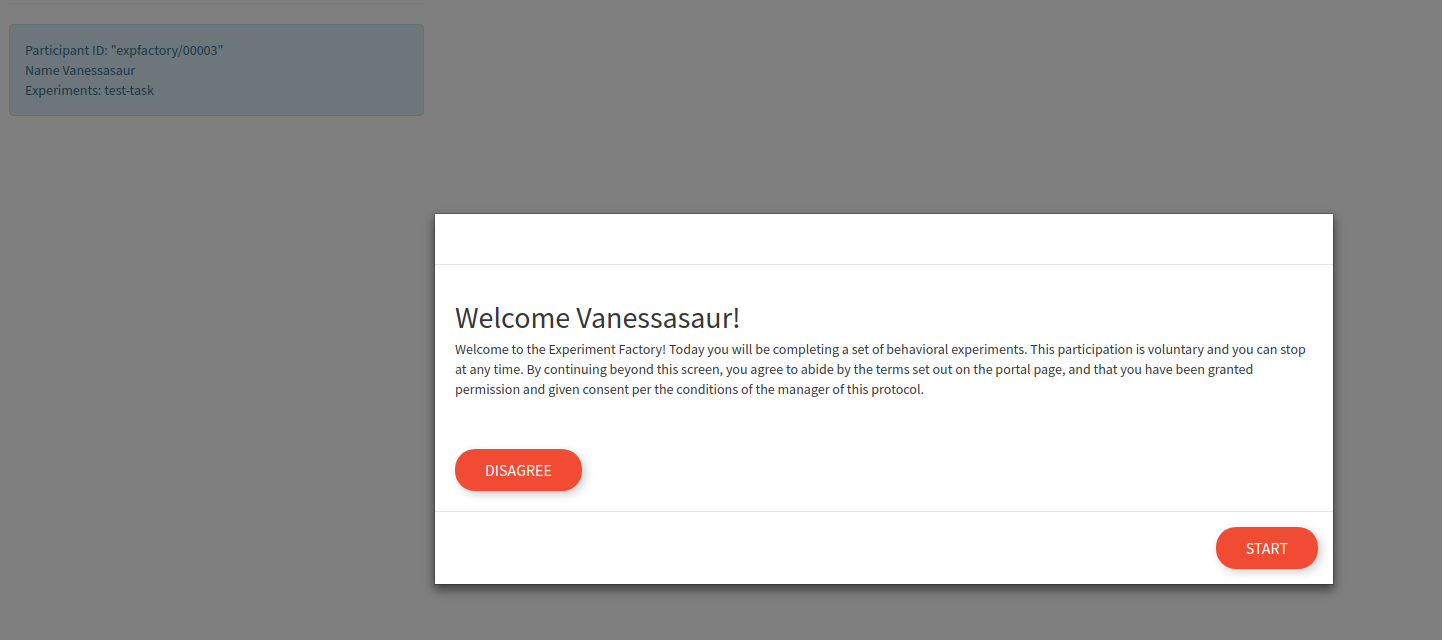

This name doesn’t get saved, it’s just to say hello to the participant. The actual experiment identifier is incremented by one for each session, and organized (for sqlite and filesystem saves) based on the study id defined in the build recipe (e.g., expfactory). After proceeding, there is a default “consent” screen that you must agree to (or disagree to return to the portal):

Once the session is started, the user is guided through each experiment (with random selection) until no more are remaining.

When you finish, you will see a “congratulations” screen

It’s up to you, the experimenter, to save the generated subject id in a secure place associated with the actual person. I have intentionally not made it easy for this database to do that for you. At this point, you could find your results in an organized fashion on your local machine, or in a sqlite, postgresql, or mysql database.

Good Practices

Generally, when you administer a battery of experiments you want to ensure that:

- if a database isn't external to the container, the folder is mapped (or the container kept running to retrieve results from) otherwise you will lose the results. It's easy to map a folder, and then stop the container when it's not being used.

- if the container is being served on a server open to the world, you have added proper authorization (note this isn't developed yet, please file an issue if you need this)

- fully test data collection and results before administering in "production"

How can I Contribute?

Feedback Wanted!

A few questions for you! I’d like to do further development based on your wants and needs. Specifically, I’m interested in:

- what kind of production deployments are wanted? A trivial addition would be a password protected portal, or pre-generated logins to send to users via a link. I would (and am hoping) there is interest in automated deployment to a cloud (e.g., AWS or Google Cloud). We can do that I think.

- Is a user allowed to redo an experiment? Meaning, if a session is started and the data is written (and the experiment done again) is it over-written?

- How would you want to customize experiments? Deployments?

It’s important to discuss these issues. Please post an issue to give feedback.

Contribute Content and Ideas

You can contribute in so many ways!

- contribute your experiment to the library, or ask for help to do so

- provide feedback on existing experiments

- provide feedback on the current software or library infrastructure

- contribute tests or other continuous integration for individual experiments

Get Help!

The Research Computing Center at Stanford is here to support you and your work! If you are looking for help to set up a set of experiments or just have questions, please reach out to us.

My heart belongs strongly with open source, and if this work can be useful to just one lab, then it’s worth it! I’d also like to give a shout out to Poldracklab for (still) being the best, to Josh de Leeuw for inventing JsPsych, and the tag team of Jonathan Nicholas and Christian Battista for awesome work with Phaser. I am also excited for (soon) collaboration with labjs.

Please reach out if you have an idea for an integration, or another experiment, or a further development to the core software! We can build all the things.

tiny little pieces… assembled for behavioral science.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "The Experiment Factory (v2.0) Beta." @vsoch (blog), 19 Nov 2017, https://vsoch.github.io/2017/expfactory-beta/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).