I wanted to make a web application that understood containers. As a researcher, or a developer, I want to be able to drop my containers into a folder, and then have the application serve them without any additional work. So I made a proof of concept, Singularity Nginx:

What does it do?

The basic idea is that I can get json or text output from a Singularity container, via a web interface.

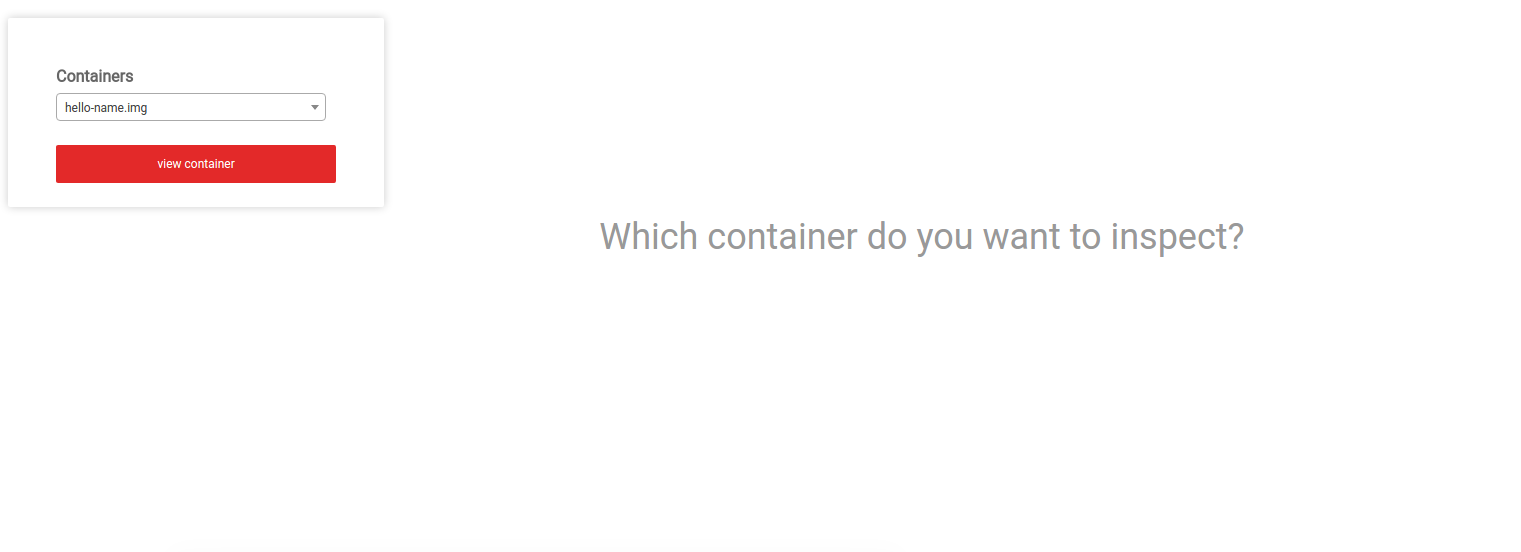

Inspect Containers

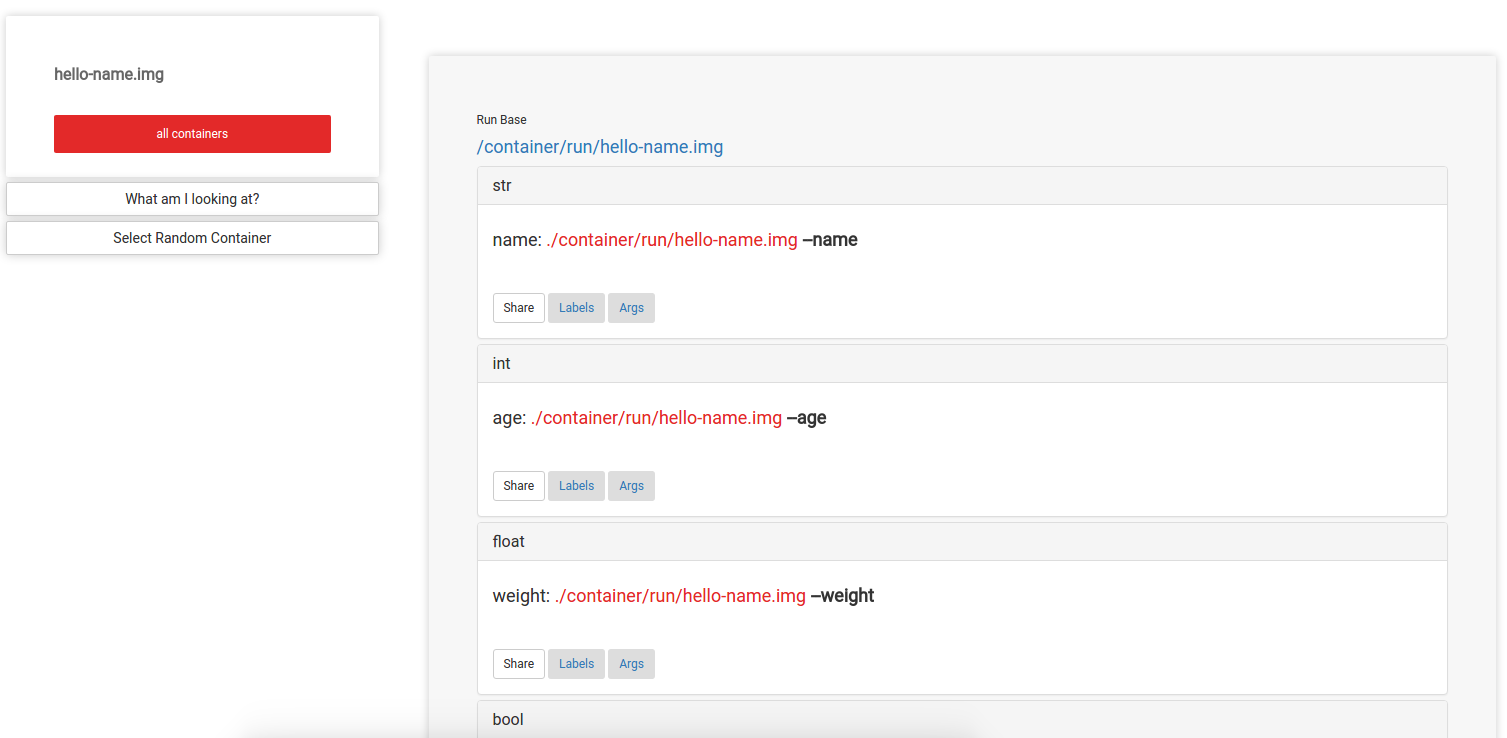

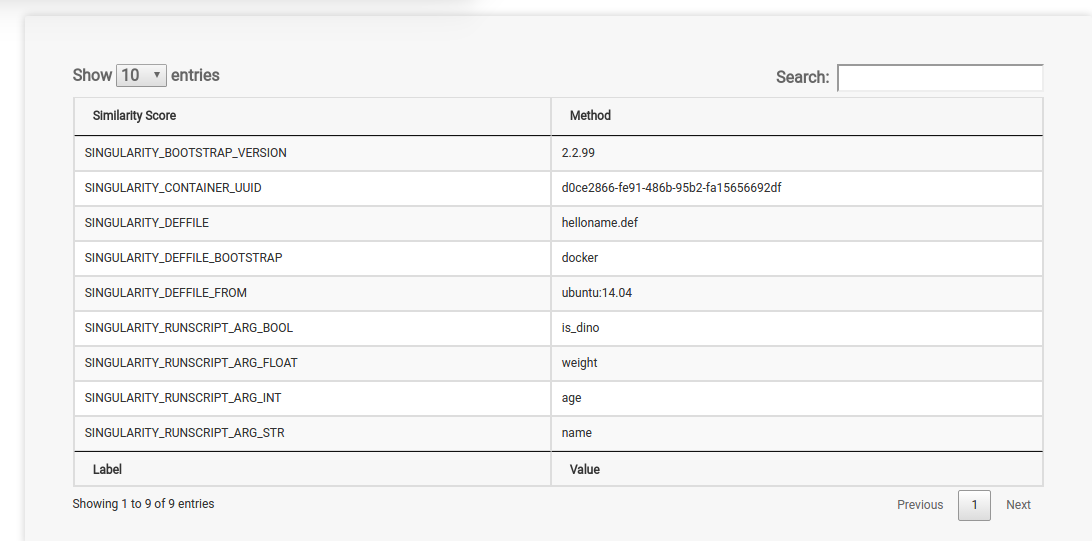

This means I can either use the container interactively in my browser, or have a programmatic call to a container’s endpoint to retrieve the same. From the home screen, I can inspect a container to see the arguments that it allows:

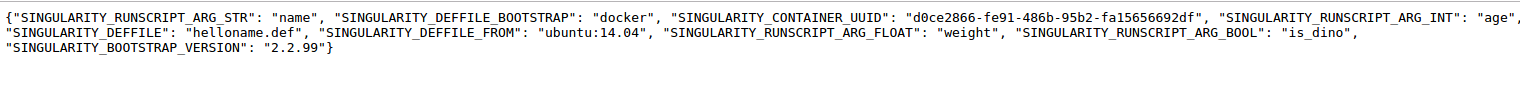

and I can look at a json response for it’s labels:

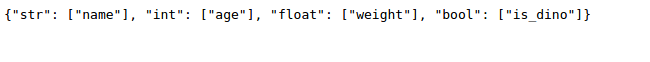

or for it’s allowable input arguments:

Run Containers

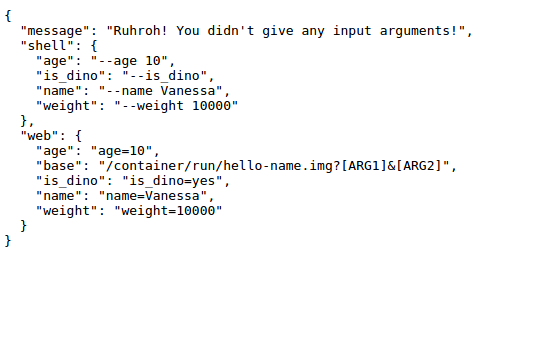

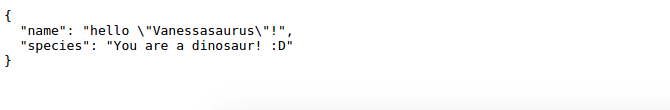

If you notice the url at the top, each container has it’s own run url, and it’s basically a mapping to the container’s name in the folder. For example. the container hello-name.img is run at the endpoint /container/run/hello-name.img. If we go to this url without any input arguments, the container has been designed to print a python dictionary (which is a json object) that tells the user how to use it:

We then add input arguments as parameters, for example, here is the output by defining the arguments name (a string) and is_dino (a boolean):

The arguments, along with metadata about the container (labels) are also served by the application, and this could be extended to include environment information, although I am cautious to blindly spit out environment variables in the case of keys, etc.

Ideas for use Cases

Why would you want to use this thing?

Publication and Analysis Demo Server

If you are a small group or lab, you might want a nice place to drop methods / applications / containers associated with publications where a user can demo your thing. It would be trivially easy to allow for a user to download the container itself (with an added view to do so) so he or she can decide to scale the operation. You could even run it without the Docker server, and use an open port on a shared server with Flask installed by a user to run it (I know this because I deployed many Flask applications in places where I shouldn’t have as a graduate student, heh.)

API for Demo Applications

You might also want to use it as an API for other web applications that you build. Given that the responses returned are text/json, a call to the server could return responses to your other (even static on Github pages) applications via Ajax calls, and you would have a nice framework for again sharing your work.

Scaling?

I don’t see this as being an optimal solution for scaling the running of the container. If you intend to scale something, it’s likely more optimal to not be using a single server.

How does it work?

Let’s chat briefly about the application itself. It’s a Dockerized application, so once you start the application with docker-compose up -d, you can drop Singularity images into a data/ folder, and they are found by the application, as we can see in the pictures above. Each container page also include a nice table with all of the labels for it:

Development

I started with the idea to integrate a Singularity container natively into nginx, but realized that I wanted much more than the web server to blindly run the container. I then moved to the simplest web application that included a server, meaning using Flask. To be completely honest, I was preparing a demo application for an algorithm in my lab, and trying to do it quickly. I’ve made this mistake before, but I first started going against my gut and essentially hard coding the algorithm into a simple Django (also Python) application.

I almost immediately hit the problems that I had anticipated. Namely, that running the model would slow down the web application, even when using a task queue (a worker called Celery) and would introduce a complicated setup because it must be loaded just once (and a server restart would trigger many bugs). It was also extremely annoying to add dependencies like tensorflow into a simple web application. I knew from the getgo that I really needed a separate server, and that it should be container based to allow for “plugging in” the next flashy model that was to be shared. This is when I scrapped the current project, and decided to start over with Singularity Nginx. Let’s talk about the thought process I went through to design this application.

Designing Containers

The Singularity container was a good starting base because it would encapsulate all dependencies for some analysis in a portable environment, and expose functions via a runscript that is executed when you run the image.

The Runscript: Singularity

So for example, if my container is called hello-name.img it might have a runscript (the thing that gets run when I do ./hello-name.img that looks like this:

#!/bin/bash

exec python /hello-name.py "$@"

Yeah it’s pretty silly, haha. We run a script at the base of the container called hello-name.py, which is a stupid script that uses argparse to parse input arguments, and render a json response for the user. Actually, it looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import argparse

import os

import json

import sys

def get_parser():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Hello, you!")

parser.add_argument("--name",

dest='name',

help="The name to say hello to.",

type=str,

default=None)

parser.add_argument("--age",

dest='age',

help="The age of the user",

type=int,

default=None)

parser.add_argument("--weight",

dest='weight',

help="How much does the user weigh?",

type=float,

default=None)

parser.add_argument("--is_dino",

dest='is_dino',

help="Is the user a dinosaur?",

default=False,

action='store_true')

return parser

def main():

parser = get_parser()

try:

args = parser.parse_args()

except:

sys.exit(0)

response = dict()

if args.name is not None:

response['name'] = "hello %s!" %(args.name)

if args.age is not None:

response['age'] = args.age

if args.weight is not None:

response['weight'] = args.weight

if len(response) > 0:

if not args.is_dino :

response['species'] = "You are not a dinosaur."

else:

response['species'] = "You are a dinosaur! :D"

# If the user didn't provide anything, tell him or her how to use the image

if len(response) == 0:

response = {'message':"Ruhroh! You didn't give any input arguments!",

'shell': {"is_dino": "--is_dino",

"age": "--age 10",

"name": "--name Vanessa",

"weight": "--weight 10000" },

'web': {"base":"/container/run/hello-name.img?[ARG1]&[ARG2]",

"is_dino": "is_dino=yes",

"age": "age=10",

"name": "name=Vanessa",

"weight": "weight=10000" }}

print(json.dumps(response))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

You don’t have to use Python, of course. The only important thing about the runscript, if you want to make a good container for Singularity Nginx, is that it should have named arguments. Those named arguments are essential for explicitly specifying variables in the url. In the case of a demo that might select a random input data and spit out a result, you can also choose to have no input arguments. This gives us some best practices for these runscripts. You want some executable file that 1) accepts the input arguments that you defined, with the correct format, 2) the arguments should be named, like --name from the command line, 3) the output to the screen should be some text or json response that can be rendered as you would need, 4) you should remove unnecessary print statements from your application, because they would go to standard out and be returned with the response, and finally 5) given that your container has input arguments, you should have the default behavior (when the user doesn’t provide input arguments) to return a message to the user to tell him or her how to run it. Speaking of these input arguments, how does the container know about it’s input arguments, and how does the web application?

Container Labels

A new feature of Singularity, that will be released with 2.3 (this is currently the development branch) is something that I’ve been pushing for, labels! Docker already has them, and they are essential to preserve metadata about the container. About five minutes after we pushed this to the development branch, I realized they also served another powerful purpose - to allow for third party applications to interact with containers. What we are going to look at below is a build definition file for a container, meaning it’s the recipe to create it. If you are familiar with Docker, this is akin to a Dockerfile and is appropriately called Singularity. It has two simple components - a header with some variables at the top, and then chunks of things in sections, each named with an argument like %post.

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu:14.04

%files

hello-name.py /

%labels

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_STR name

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_INT age

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_FLOAT weight

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_BOOL is_dino

%runscript

exec python /hello-name.py "$@"

%post

apt-get update && apt-get -y install python

The build spec above says that we are going to be bootstrapping a Docker image, meaning dumping a bunch of Docker layers into our image. We are then going to use %files to add our runscript to the container, copying hello-name.py from the build directory (using a relative path) to the container base at /. For the labels, specifically for this Singularity Nginx application, I defined a very basic schema that tells the application the label is an input argument. It is the argument type (eg, str, int, float, or bool) appended to SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG. Each can be a comma separated list of the named arguments, so it could also look like this:

%labels

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_STR name,ice-cream

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_INT age

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_FLOAT height,weight

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_BOOL is_male,isHungry

and it should work to give them to the container as named arguments, like:

./hello-name.img --name Vanessasaur --weight 10000 --is_dino

When this gets translated to a url, it would look like this:

/containers/run/hello-name.img?name=Vanessasaur&weight=10000&is_dino=true

The string after is_dino doesn’t actually matter. The application knows it’s a boolean, and so if it’s defined it will be akin to finding the flag when running on the command line. The input types are important, because each input is stripped of most non alphanumeric characters, and only single words are allowed. An argument that is not defined does not pass through. The container creator could simply not define any input arguments, in which case nothing would be allowed to pass through to the container, or only expose a small subset for demo purposes. If we look at this example again:

%labels

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_STR name,ice-cream

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_INT age

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_FLOAT height,weight

SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_BOOL is_male,isHungry

I want to note that the capitalization of the label names (the first in each pair) does not matter - all label names are converted to uppercase. The label values themselves, however, will not be parsed. For each of the above, we would expect the container to be run with something like:

./container.img --name Amy --age 10 --isHungry

You might be curious how the labels are stored with the container. With Singularity version 2.3, we have a new metadata folder stored in the base of the image at /.singularity. This is a new addition that is allowing for more fine tune control of the environment, labels, the runscript, and any other cool things we think of! Some of this functionality might be eventually replaced by an image header proper, but this is an improvement for now. So - the labels are stored with the container in /.singularity/labels.json as:

{

"SINGULARITY_DEFFILE_BOOTSTRAP": "docker",

"SINGULARITY_DEFFILE": "Singularity",

"SINGULARITY_DEFFILE_FROM": "ubuntu:14.04",

"SINGULARITY_CONTAINER_UUID": "4035ee00-78ff-4b7f-b679-0e5e95155102",

"SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_STR": "name,ice-cream",

"SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_INT": "age",

"SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_FLOAT": "height,weight",

"SINGULARITY_RUNSCRIPT_ARG_BOOL": "is_male,isHungry"

}

And when the container is run via this application, the user (or application making the post) can retrieve the labels, and then would allow for a url that looks like this: http://localhost/container/run/container.img?name=Amy&age=10&isHungry=1. I’ll also note that the functions to interact with Singularity from Python are not native to this application, they come from the Singularity Python client, which also drives views for Singularity Hub, the builders, generation of interactive visualizations for containers, and calculation of similarity metrics between containers, which drives this visualization. This is the library of “all the extra stuff” that has too many dependencies to be included with Singularity proper, but I just had to have them somewhere!

Deployment

Using Docker and docker-compose makes this pretty easy to deploy. Given a server with these dependencies, you can basically clone the repo, and build the container, and then bring up the application;

git clone https://www.github.com/vsoch/singularity-nginx

cd singularity-nginx

docker build -t vanessa/singularity-nginx .

Storage

I was originally going to make an endpoint to Singularity Hub to pull and use any container available, but that immense freedom made me a little uneasy, so I scoped the intended use case of this first version to be more controlled. This means that the user can pull (or build/transfer) the containers he or she wants to provide to the data folder at the application base. This can be done from inside or outside of the container, as long as the file gets there. The folder is mapped to the host, so anything on the host will be available in the container. For example.

cd data

singularity pull shub://vsoch/singularity-images

I provided the build specification files, and the commands to generate them, with the code repository, so you can build the example images to get started:

cd data

./generate_demos.sh

After building and starting the application with docker-compose up -d you can go to 127.0.0.1 (localhost). The containers available will be shown on the screen.

Future Development

Container Permissions

If you are familiar with making requests to a browser, viewing a page is a standard GET. A POST is more common for APIs, for several reasons. Thus, I see an ideal implementation providing usage information via GET in the browser, and then running containers via POST, ideally with authentication in place to give more detailed permissions for running containers.

Data Folder Mapping

An easy change would be to either allow the data folder to be selected interactively (less ideal for a web application but great for running locally where your containers are eeevvvrrreeee-whaaare!) or simply mapping another folder (external to the application base) to some data folder (e.g., /data in the Docker image) to serve containers. You of course would not be able to do this on a server where you don’t have sudo permissions, which is why I chose to keep data in the application base for this version.

Scalable

As it is, this deployment is a single server with gunicorn workers, meaning that it’s not going to handle 1000 calls to run a memory intensive application. Thus, an approach that uses load balancing, or whatever implementation of cloud cluster for containers you would want, would be useful to have. I’ve been thinking a lot about a slurm equivalent for the cloud and I’m not convinced that it’s a solved problem. There is lots of potential for building cool things there :)

Local HPC

This idea maps very seamlessly to be a “run on server thing” to be a “run on HPC cluster thing” and submit jobs to SLURM, SGE, or just manage and use containers. Likely I’ll implement this next, because I’ve always wanted to give a go at a terminal in a browser! I know I know, Google has already done it. I still want to try. Just need to find some more free time, lol.

Summary

Please provide feedback in the comments below, or on the issues board! I literally put this together in a day in a half, so yeah, it’s rough. I’m ok with this. Thanks for reading!

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Serving Singularity Containers." @vsoch (blog), 19 Mar 2017, https://vsoch.github.io/2017/singularity-nginx/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).