How hard would it be to serve tens of thousands of Datasets on Github Pages, but also tag them with Schema.org for discovery with Google Datasets? This is a followup to a previous post on creating different kinds of metadata for a single Dockerfile using schema.org. While I’m still working on the definition for a Container proper, an easy first thing to try would be to do this same task, but representing the Dockerfiles each as a Dataset. This is what we are going to talk about today.

The Dataset

The dataset I am going to be working with is from the the Dinosaur Dataset Dockerfiles collection. Specifically, I am working with a subset of 60K that I filtered for having Python libraries included within. I made this choice because when we define the Container specification and extraction using container-diff, I want a nice list of pypi packages returned for our example. But that will be a future post.

The Metadata

What Metadata is Needed?

While we will eventually want to show that we can extract useful metadata describing a Container Recipe, to start we will do the same for a smaller set defined for the schema.org Dataset, a subset required for Google Dataset Search. The only required fields include:

- name

- description

Haha, only two! The rest (e.g., license, keywords, citation) are actually “recommended” but not required. Two is a fairly small set. I think Google is starting with a “Keep it Simple Stupid” approach - good search doesn’t necessarily mean “Let them search all the things!” but sometimes “Let them search the most meaningful and distinct things.” I agree.

How do we extract the Metadata?

To extract metadata from the original set of over 100K, I wanted a smaller, more meaningful set.

I created a second version of the original Dockerfiles repository with

a smaller number of files (60K), hosted at openschemas/dockerfiles,

and within it scripts and functions to use the schemaorg python

python client to generate a page for each Dataset. While not discussed today, this same

base generates specifications to describe the same Dockerfiles as SoftwareSourceCode and

(the most detailed one) ImageDefinition (or container recipe). If you are interested in the

extraction, see the repository. Briefly, I wrote functions for each extraction type and then used them

as follows. We first recursively search for Dockerfiles:

from helpers import ( recursive_find, root )

files = recursive_find(root, "Dockerfile")

and then we import and use the extractors to write the html page.

from specifications.Dataset.extract import extract

from specifications.DataCatalog.extract import extract as catalog_extract

for dockerfile in files:

dirname = os.path.dirname(dockerfile)

output_html = os.path.join(dirname, 'Dataset.html')

extract(dockerfile,

output_file=output_html,

catalog=catalog,

contact=contact)

And it’s pretty fun to watch :)

I have a version to run scaled on our Sherlock cluster, but meh, this is more fun and gave me an excuse to (finally) go for a run outside.

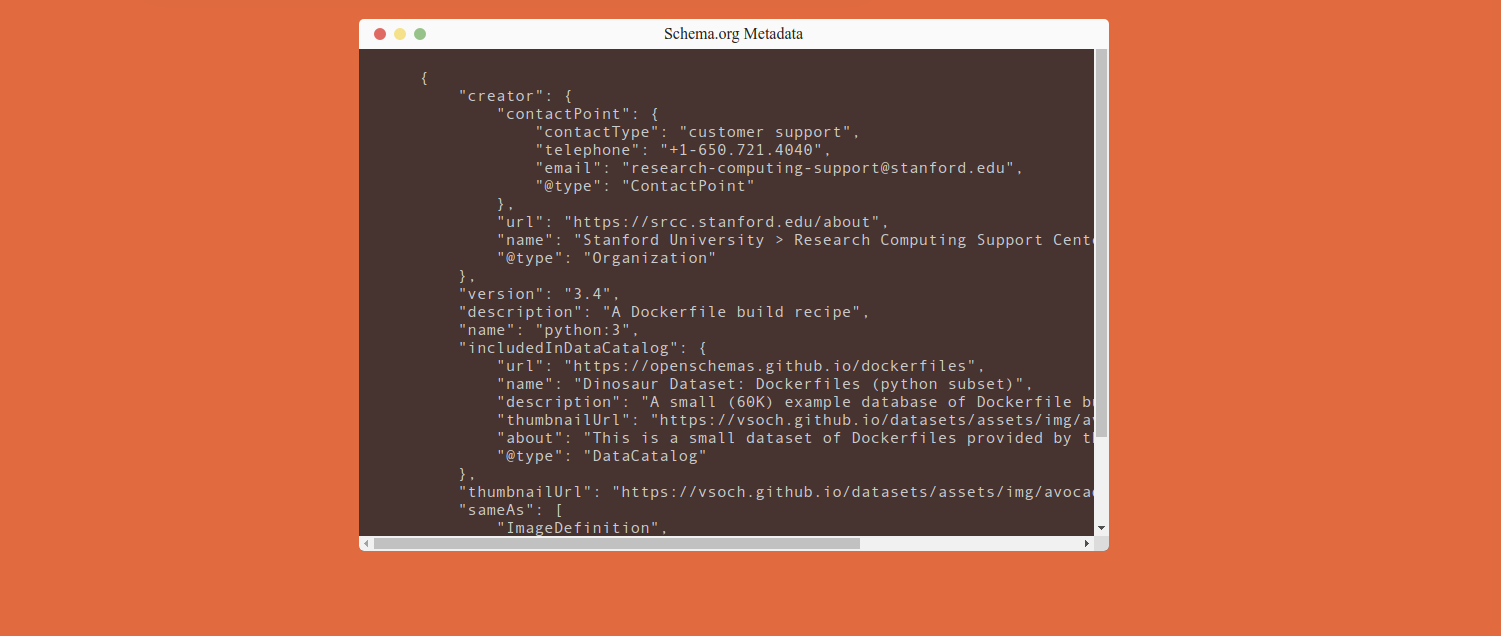

What does the metadata look like?

As we previously showed, the Dataset page has a nice visualization of the metadata contents:

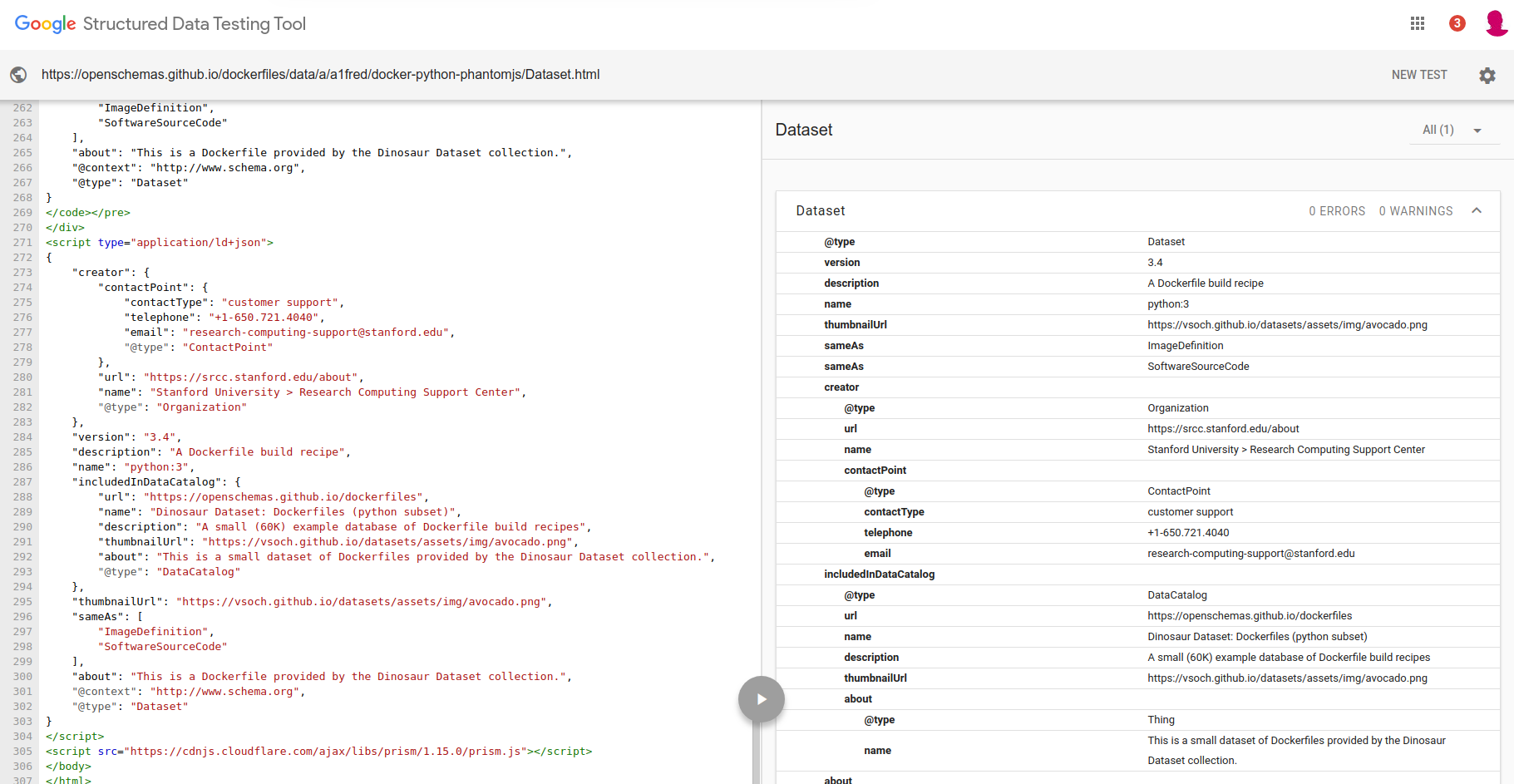

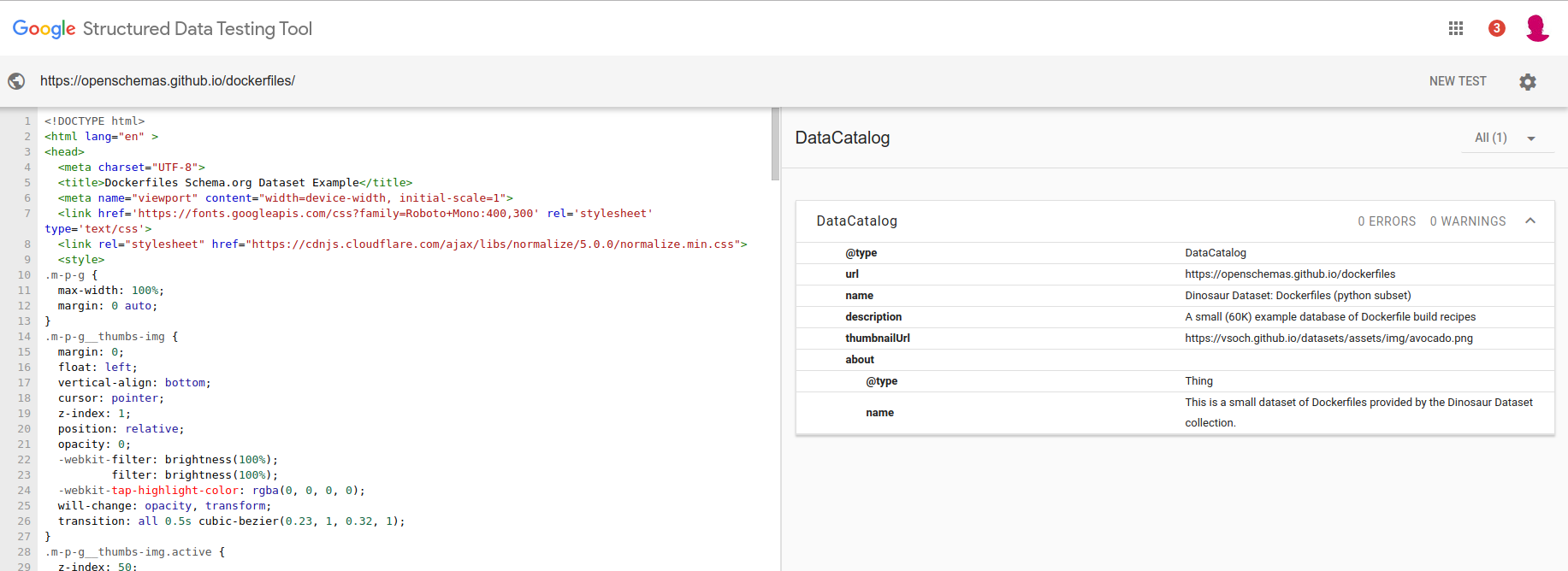

But this “human friendly” part isn’t what the robot would index. Here is the same view of the page, but from the Google Dataset validation tool. We can see there is a script tag with json-ld as the type. The user doesn’t see this, but importantly, all the information there is represented in the page they can see.

How do we organize the datasets?

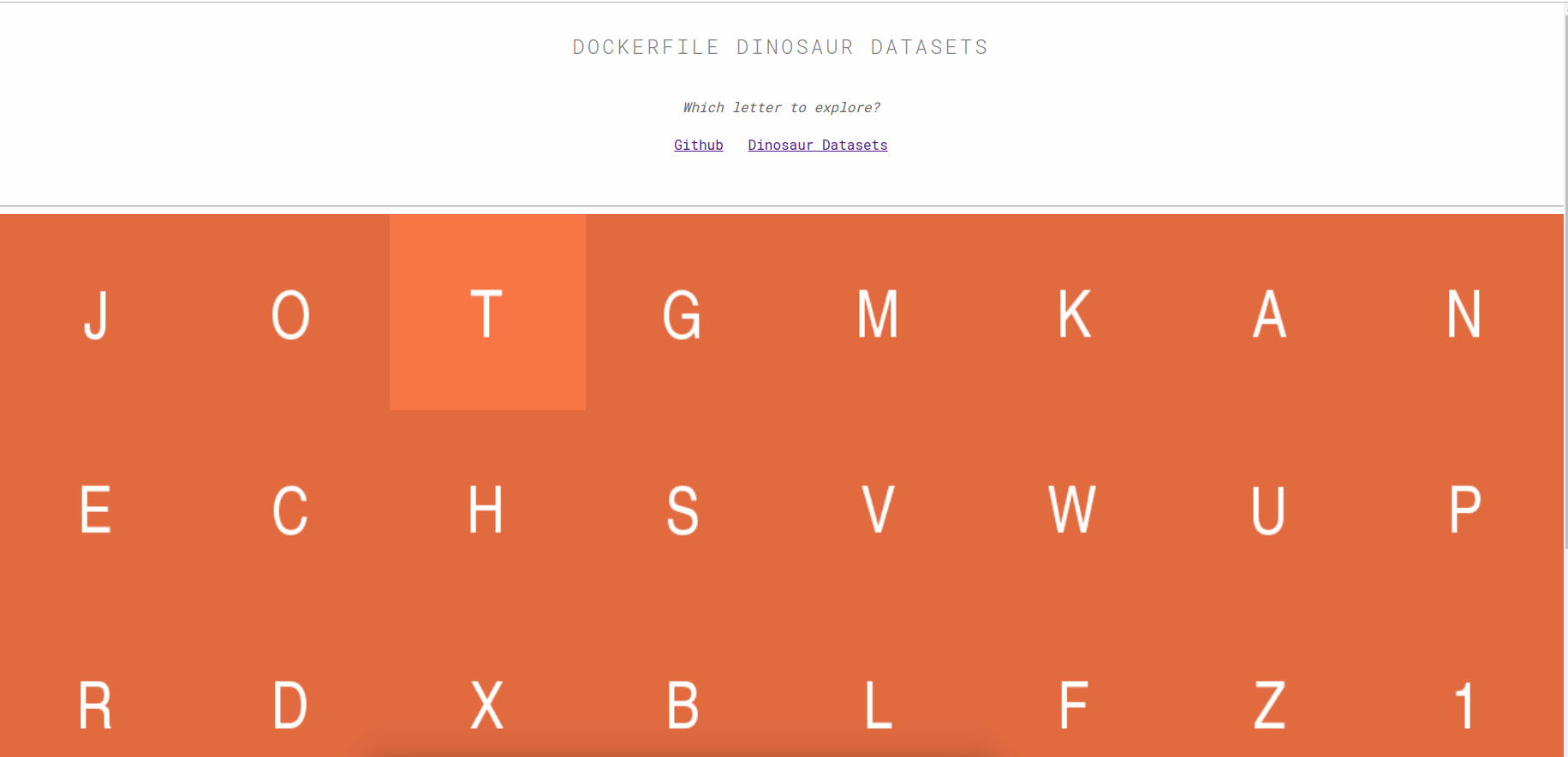

I chose to group the datasets into a data catalog, and then to make the catalog accessible via the main entrypoint to the dockerfiles Github pages, a master page where the user is directed to choose a letter.

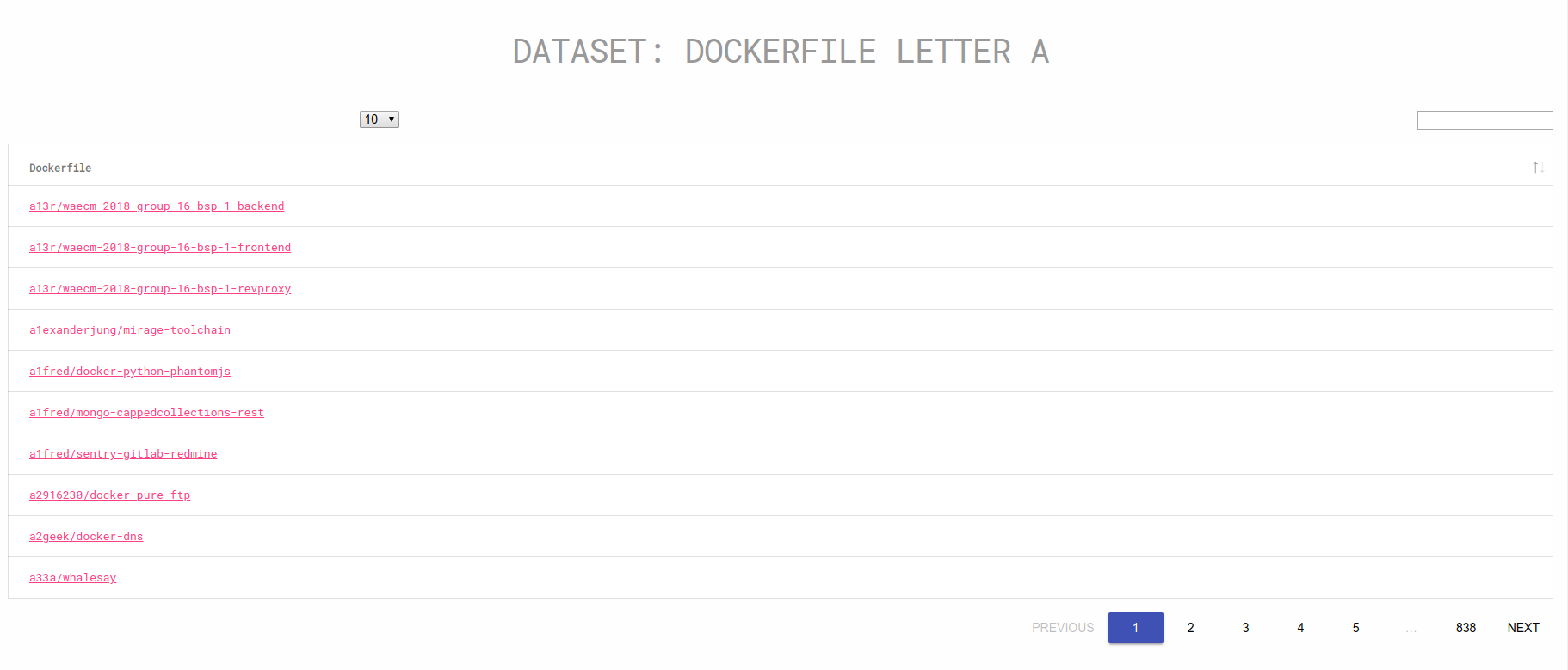

This template is provided in the dockerfiles repository (but not yet schemaorg python). What schemaorg python does provide is a set of functions to easily generate a table for some set of objects. The reason I chose the “letter approach” above is because we have ~60K total, which would blow up the browser in most cases. Here we can see one of those tables, the table of container recipes for the letter “A”:

What does the letter A spell? Avocado!

Before I forget, here is the Data Catalog metadata view:

Arguably, if the DataCatalog is found at the root, and the links contained from there include the DataSets, I’m hopeful they might be found by the Google bots. I think worst case I would need to add a proper sitemap.xml, but I’ll look into these details when I have the other schema.org types ready to go. More importantly, both the DataCatalog and each Dataset are validated as correct using Google’s Structured Data Testing Tool.

What level of representation?

You might notice that I’m thinking of each Dockerfile as a container, and it follows that each unique container is a unique Dataset. It could also be the case (possibly more efficient for search) to just call this entire repository one dataset. This would likely be the better thing to do if this were more than testing. For now, I’ll say that

the choice of a level of representation for a Dataset is entirely dependent on the data and user needs

The level should match what you expect a user searching for it would want to optimally find.

Why Should You Care?

You should care because

It needs to be easy to make datasets and other resources programmatically discoverable and moveable.

Why? these simple operations already are (and will continue to be) essential as the number of containers, datasets, widgets, and avocados explodes. It’s already passed a human’s ability to manage, so we are late to the game. This goal requires both tools and training for said tools. To help with this goal, along with schemaorg python I’ve released (and continue to work on) a repository of extractors as examples and functions for you to use!

What is an extractor?

Each extractor is a folder, named by the entity in schema.org, that includes

a recipe file to validate your extraction against (recipe.yml) and a python

script with a function for you to use to do this (extract.py). For example,

to generate a nicely rendered web page for some SoftwareSourceCode that I have,

I could do this. First clone the repository:

git clone https://github.com/openschemas/extractors

cd extractor

Then open up an ipython terminal, for a quick demonstration:

from SoftwareSourceCode.extract import extract

I can look at the function header to see what is required (or suggested) by me:

def extract(name, description, thumbnail=None, sameAs=None, version=None,

about=None, output_file=None, person=None, repository=None,

runtime=None, **kwargs):

''' extract a SoftwareSourceCode to describe a codebase. To add more

properties, just add them via additional keyword args (kwargs)

'''

...

Let’s give the minimum requirements, and leave the rest undefined. Note that

these are properties that I (as some opinionated person) think are important,

and this preference is reflected in the recipe.yml also included in the

folder. Also note that there are many more properties not described here, and

you could add them as key word arguments (kwargs). We can see quickly see the

total number of properties for SoftwareSourceCode by creating an instance:

from schemaorg.main import Schema

Schema('SoftwareSourceCode')

Specification base set to http://www.schema.org

Using Version 3.4

Found http://www.schema.org/SoftwareSourceCode

SoftwareSourceCode: found 101 properties

Wow, 101 properties! I won’t even live that many year probably. Anyway, to continue! If I wanted to extract a simple instance for a SoftwareSourceCode, I’d just need to do this:

instance = extract(name='sregistry', description='Singularity Registry Server')

When you run that command, you’ll see the recipe pop out on the screen, along with the Schema.org load shown above. If I were to provide an output html file, it would generate that pretty page above. I could add that to my Github Pages, and I’d be done!

instance = extract(name='sregistry',

description='Singularity Registry Server',

output_file='index.html')

Properties

For advanced usage, you can look at the properties allowed under instance._properties,

the properties that are defined under instance.properties

> instance.properties

{'description': 'Singularity Registry Server',

'name': 'sregistry',

'version': '3.4'}

and what gets dumped into the metadata for a page with instance.dump_json()

instance.dump_json()

{

"version": "3.4",

"description": "Singularity Registry Server",

"name": "sregistry",

"@context": "http://www.schema.org",

"@type": "SoftwareSourceCode"

}

The above would be what is pretty printed on the page. The metadata is pretty sparse. The entire list of properties for a SoftwareSourceCode. Whew!

Next Steps

Container Metadata

I’ll update with another post when the Container metadata pages are ready to go, I need to make some pull requests and changes to container-diff so that the extraction can be performed on our cluster (and complete in a reasonable time).

What can you do?

For you I want to encourage you to:

- Ask for help for extraction for your dataset. Reach out to me, and I will help you.

- Do you see a missing example extractor that you’d like? Open an issue

- Participate in discussion! Discussion with OCI here and with schema.org here

Wouldn’t it be cool if Google could provide an API endpoint to validate our datasets? Or their own library to do the same, since their criteria for search might be different?

Have Patience

What I’m learning is that these things take time. This is hard for me because I like to work quickly, and I take it upon myself as some kind of failure if my efforts don’t always lead to a speedy result. I truly believe that this work is needed, and if we work hard to express the need, and develop examples / tools and other content that moves us closer to our goals, even if we take a long(er) time than we’d want we will get there. There was a comment yesterday by a fellow initative on “the social network made for birds” that said something to the effect of “This idea isn’t a reality yet so it’s not worth pursuring” and I realized this person likely was in a similar mindset to the one that discouraged me previously.

If you believe in something, keep believing in it.

If you keep believing in it, back that up with reasons and work that support that. If you run out of reasons, and if your work isn’t convincing, then it’s likely not something that is truly needed, and you are free to move on. But until you reach that point? Don’t give up trying.

Resources

- Schema.org Extracters

- Dockerfiles Schemaorg Subset

- Dockerfiles Github Pages

- Structured Data Testing Tool

- Schema.org Dataset

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Datasets with Schema.org." @vsoch (blog), 14 Nov 2018, https://vsoch.github.io/2018/datasets/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).