If you are a researcher with some code and you care about reproducibility, you probably use version control like Github. If you go out of your way to write a README file, a quick description of how to install, use, or otherwise interact with the repository, you are already diabolical and likely doing better than most. And perhaps this solution is best for you. But what about if you are providing some kind of open source software that others might contribute to, including the documentation? You want to make the experience of learning about your software pleasant, but still easy to ask questions and contribute fixes. You want the time between someone’s eyes going over a line and having a thought pop into their head to ask or change something, and pushing a button to do that, to be minimized. Today this is our topic for discussion. Let’s talk about Living Documentation. If you don’t want to talk about it and just want a quick template for your own living docs on Github pages, see the living docs repository, or some of the examples linked at the end of the post.

What is documentation?

When someone references documentation, they are usually referring to a texty thing that is intended to help someone understand ideas or resources. In the world of academia and enterprise software, this spans out to many things. The boundary between forums and issue boards, help desks and email support, and (more recently) chat support is one massive gray area. You are lost in the shades of gray, and no, I’m not talking about that reference, I’m talking about the doldrums where the pencil on the white page has become wet, leaving nothing but blurry graphite nonsense. Let’s zoom out a bit, and better understand the space. The core problem that these solutions are trying to solve is to provide a source of help for a user base, and typically that means some form of the following things:

Documentation

A general reference to “documentation” means the white pages, or detailed instruction manual for your resource. Realistically, nobody really reads it until they hit a very specific issue and then find a page via a Google search. The pros of documentation, of course, are that it might have the most informative details about the resource. They might be certified or approved to be written by a small team of experts, and they might even be version controlled. This does not say that they are up to date, or interesting to read. Sometimes, the most effective way to communicate a protocol is in fact straight forward and professional. The cons are that this documentation is only sometimes linked to a “Who do I ask if I have a question?” Let’s call this a problem of support. The other problem is that this kind of setup creates an artificial divide between the writer and reader. You, reader, are the audience, and the writer is put in the position as expert. It shouldn’t be like this, because even if the writer is an expert, the reader can be an expert too. The reader also has much to contribute. If documentation has a bug, it should be straight forward how to suggest a fix without searching the doldrums for a contact page with a tiny phone number or email that you are too introverted to use. Let’s call this a problem of contributing.

Tutorials

Tutorials mean that I want step by step instructions for doing something. Many tutorials are basically just documentation that has been gussied up to be pretty to look at, and written in a more friendly, storybook way. The way that I write these posts, period, is done intentionally like this, because writing these like an academic paper would be boring for both of us. It’s also easy because I talk to myself internally, anyway. But I digress! There might also be videos, asciinema, or other kind of “watch me and learn” experiences. The pros of the walkthrough or tutorial are that they are detailed and usually complete. The cons are that the state of the world changes quickly, and the next day the content is out of date. Let’s call this a problem of recency.

Email Support

Nothing is ever going to beat having interaction with another human, given that the interaction is helpful. Many automated help desks offer email support, but there are so many customers in the queue that an automated (or barely personal) message is sent back that doesn’t really solve the problem. Off the top of my head, this has been my experience with most large companies that have to efficiently provide a service. This approach will work well under two conditions. First, if I appreciate the service and it’s done well, the job well done may go unnoticed, but importantly, I am not bothered by template, (likely automated) emails. Secondly, it goes without saying that the size of the user base must match the size of the service provider. If not, both sides are frustrated because the quality and speed of the help will suffer. The cons to any kind of email approach is that depending on the openness of the requests for help (e.g., a public Google Group is completely open, whereas a private email list is not) the knowledge represented in the answers and responses may not be used to its full potential. For example, if a user asks a question to a closed system and gets an answer, 500 other users might ask the same question. If the knowledge in the answer was discoverable, perhaps 400 out of those 500 wouldn’t have been asked because the answer would have been found in a quick search. Let’s call this a problem of discoverability, and lack of it a problem of redundancy.

Chat Support

Chat support is akin to email support, except it’s interactive. The benefits of chat are that if it’s done in a “group channel” (e.g., Slack) sort of deal, you actually grow a community around your resource. Users get to interact with the support team, and it’s fun. The users also, over time, build up confidence and start to help one another. The previous small team that had to manage hundreds of users all of a sudden get a burden lifted off of them. They also get to keep a complete record of previous conversation in some cases, for future reference if a question is asked again. The con here, of course, is that we trade immediacy for organization and experience. A chat experience is a very different beastie than something organized like a tutorial or documentation.

Forum and Issue Boards

Forum and issue boards can either refer to something like discourse or (even better) if linked to version controlled code, Github issue boards. Both of these have the commonality of user accounts - you post a question or answer as your authenticated self, and so you arguably care a lot about what you write because you aren’t an anonymous internet troll. This is a good solution for accountability. The main difference between a traditional forum and an issue board is version control and topic of discussion. The Github issue board is linked to some code base that has version control, and likely the discussion is around the code. For a general forum, you might be talking about pancakes. This use case is incredibly strong, because it means that people can help one another. There isn’t a small group behind closed doors that are “the experts” and get inundated with requests for help. I would argue that for any kind of topic or question that represents some knowledge about the world that can change, it’s not such a crazy idea to want version control. If I believe the answer to something to be one way today, I’d want to update it tomorrow, but still remember what was said today.

Summary of Needs

We’ve identified that any source of documentation and support must solve the problems of having receny, accountability, discoverability, be easy for contributing, and provide support and version control. It’s a hard bite, because sometimes it’s better to focus on doing a subset of these things very well. I spent some time brooding about this, and struggled between wanting to implement some central, master solution where I’d slowly build my army of contribute friendly documentation, and thankfully one of my colleagues quickly brought me back to reality that this was not a reasonable route. Instead, I decided to take an approach that I think can possibly have more impact: implementing something simple, showing others how to do it, and then hoping that the solution can be deployed across many places to solve some of these problems. In summary, we want:

An organized, version controlled documentation base that is (visually) pleasant to read, open for edit or contribution, and easy to post general questions to. The solution should be general to be possible to add to existing documentation basis, and harness already existing technologies. It must be entirely static.

For this example I’ll show adding the static content to a Github pages (jekyll) site. This one, actually :)

Interactive Posts

I could implement this living documentation in many different contexts! On a site that offers services, it would be a hard coded page. On an integration with a third party application (e.g., Slack or other) it would be added to the code for the integration. In something like a Jupyter notebook it might be tied to a cell. For this example, we are going to discuss a common Github media, a Github pages site that is generated from an underlying Jekyll site. If you aren’t familiar with Jekyll, it’s pretty simple - we take text files in a format called “markdown” and turn them into pretty pages. Github provides a web server directly from a repository. Jekyll is a blogging platform, so it’s based on the idea of posts. A post is a little writeup that you do (about anything really) that is dated and added to a feed syndicate for subscribers of your blog to be notified. So thus, this sets up our definition of an interactive post:

An interactive post is a blog entry that renders from a version controlled repository, is read on a pretty page, and provides the reader with easy access to an editor to suggest changes, or an issue board to post a question for discussion.

For the above, the issue board should have a link to where the user was coming from. The discussion is also easy to search, possibly organized by one or more categories. The content itself also requires no specialized knowledge about programming languages. It is nothing more than text, minimally with an intuitive syntax.

Technologies Used

We are going to show a solution that doesn’t require any extensive experise or bleeding edge technology. This means we are going to use already existing things! First I’ll show you the solution, and then how I did it. Here we have a blog entry, and we are reading about… this post!

But hmm, we have a question. We see the little ellipsis in the top right, could that give us some power to do something? We explore…

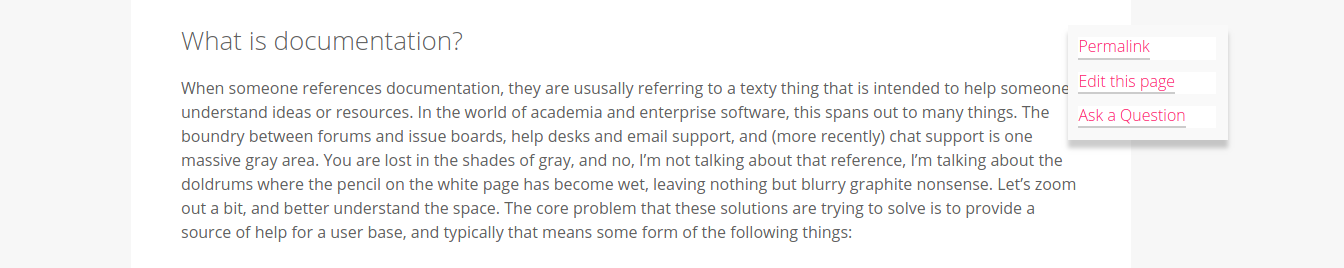

Why yes! We see that we can grab a permalink (maybe send to someone or share on social media), ask a question, or edit the page? Would they allow me to do that? Let’s see what happens if we want to ask a question:

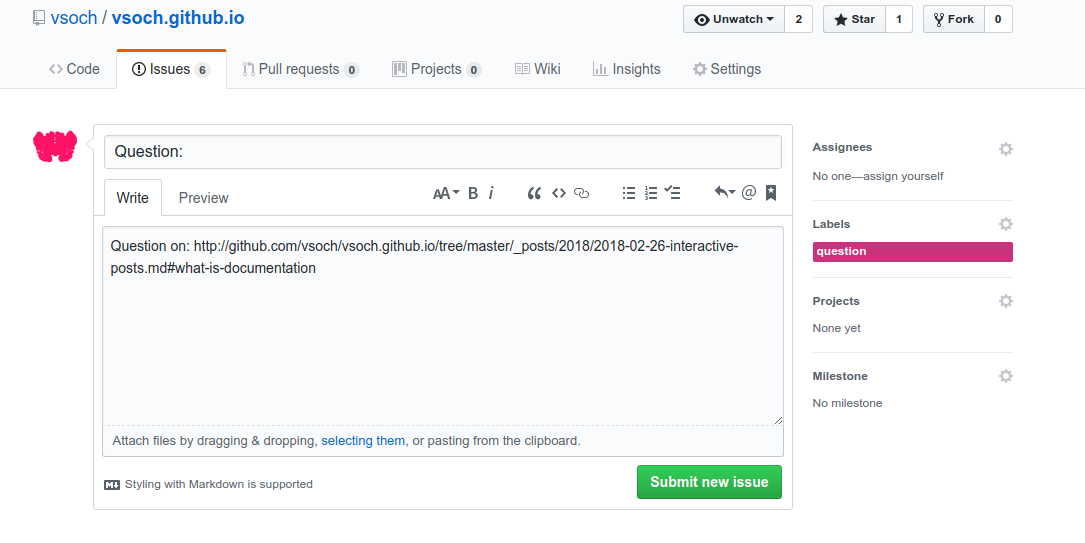

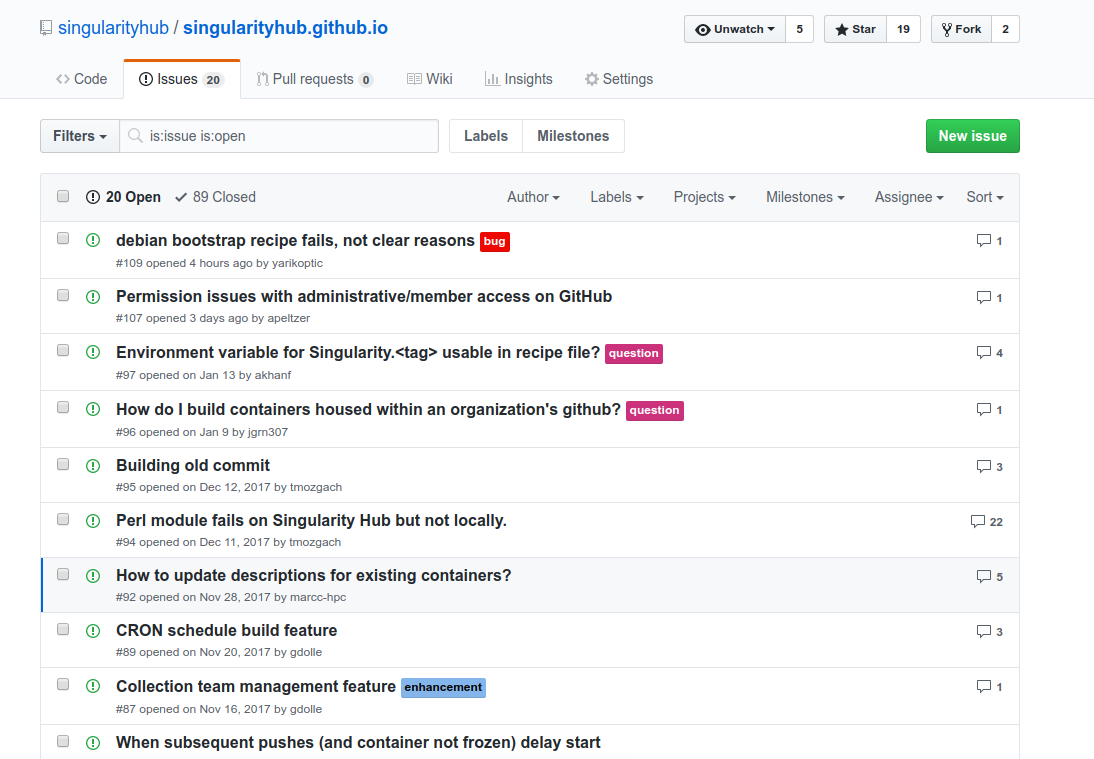

It opens up to a new issue on the Github board that the site renders from. And it’s labeled with question and linked to exactly the file and location where I was asking it. That’s cool! What about if we had clicked to edit the page?

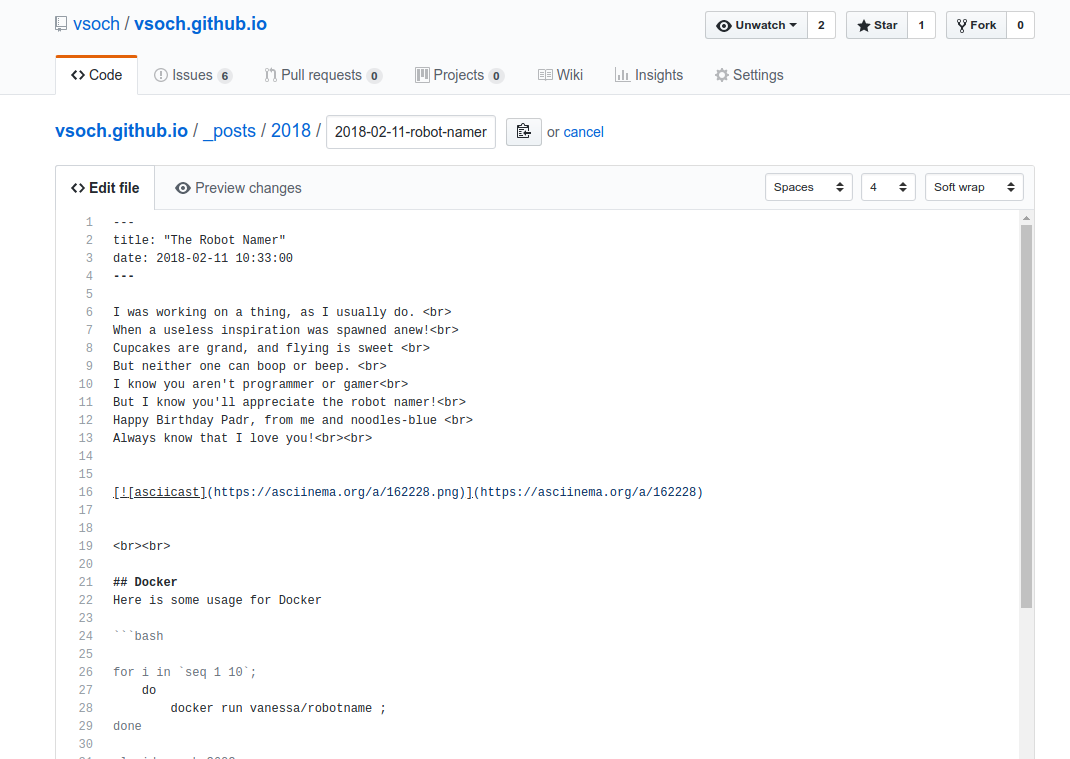

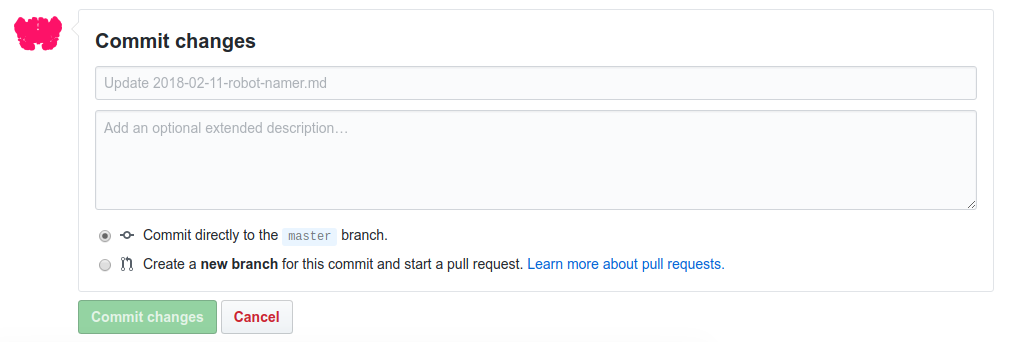

We open up to a traditional Github editor, where we can make changes, and after you make changes, you can either be commit directly to master branch (if you have this power) or to open a Pull Request (PR) to ask the maintainers of the repository to discuss changes. Even if you don’t want people to contribute, this is really nice for personal review and editing.

Why is this simple flow powerful? Because it means that while the user is reading your nicely rendered documentation, they are never more than about 300 pixels away from a button to take them exactly to a linked place to ask a question, or suggest a change. It’s also powerful because the entire organization of the issues and documentation is backed by Github. This means version control, and if you have some basic familiarity with the Github APIs, you know that you can extend your content in so many other ways. Even if you don’t do this, you can search all past questions and commits via Github’s nice user interface.

Headlines

These are those weird “h1” through “h6” tags (more) that you see in triangle braces in html syntax. The cool thing about them is that for Jekyll, if we render a section of markdown like this:

# This is my title

it will add an “id” attribute, rendering to:

<h1 id="this-is-my-title">This is my title</h1>

and what you might not know, is that this serves as a relative link on the page! If your page is at https://superman.org, and you have that header with id, you can jump directly to it with the url https://superman.org#this-is-my-title. Why is this great? It follows quite nicely that if you have a loooong page of text with various levels of headings, we can get a link to each section of the page for directly linking there in other places. Cool!

Github

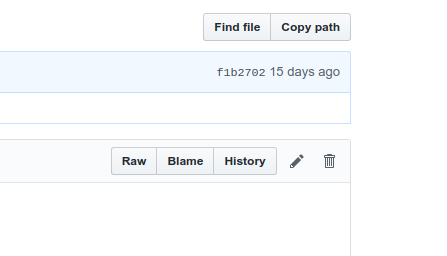

Oh Github, how much do I love thee, let me count the ways! If you look in the top right of some file in a Github repository, there is a tiny edit symbol.

When you click it, you get a nice editor we saw previously. How is this done? The format of the link is very predictable.

[repository url]/edit/[branch]/[file]

https://github.com/vsoch/vsoch.github.io/edit/master/_posts/2018/2018-02-11-robot-namer.md#docker

The same is true for the link to create an issue, including other fields like a label, a title, and the post message body. There are other things you can specify if you look at the Github API documentation for how to create an issue.

[repository url]/issues/new?[variables]

https://github.com/vsoch/vsoch.github.io/issues/new?labels=question

The variables # and space above need to be url encoded to %23 and %20 respectively. So how do we implement this in the website? Very easily! Given that we are using jekyll that has common template for a post (under _layouts/post.html) we can create a file called editable.html to include (in the folder _includes, and all this means is that I can write a line to include it in any other layout or include page) with the following steps done in a script:

- Find all the header tags

- Append a dropdown menu

- Add links to the menu for a permalink, to ask a question, or edit the page

That looks like this:

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

// Here we select all the headers, h1 through h4

var divs = $("#h1,h2,h3,h4");

// The Jquery "each" will loop through the list that we find

$.each(divs, function(i,e){

// The div id is the id=this-is-my-title that we saw above

var did = $(e).attr('id');

var start = "<div class='dropdown more'><span><i class='fa fa-ellipsis-h more' title='Edit'>";

start += "</i></span><div class='dropdown-content'>";

// Permalink

var link = "https://vsoch.github.io//2018/interactive-posts/#" + did;

var button = "<p><a href='" + link + "' target='_blank'>Permalink</a></p>";

start += button;

// Edit

var link = "http://github.com/vsoch/vsoch.github.io/edit/master/_posts/2018/2018-02-26-interactive-posts.md#" + did;

var button = "<p><a href='" + link + "' target='_blank'>Edit this page</a></p>";

start += button;

// Issues;

var link = "http://github.com/vsoch/vsoch.github.io/issues/new?labels=question"

link += "&title=Question:&body=Question on: http://github.com/vsoch/vsoch.github.io/tree/master/"

link + ="_posts/2018/2018-02-26-interactive-posts.md%23" + did;

var button = "<p><a href='" + link + "' target='_blank'>Ask a Question</a></p>";

start += button;

// Here we append the content that we built up in "start" to e, the header node

start += "</div></div>";

$(e).append(start)

})

});

</script>

and there is some additional styling (not shown here) that takes care of the alignment and spacing. What does this mean?

Anywhere that we have a header on a post page we have automatically generated permalinks, help and support links! We do this once, and we’re done. All future users will be able to quickly get help or suggest a change.

Notice that I chose to pass the variables for ?labels= and ?body= and &title= through the url, and these show up in the issue. I figured this out by trial and error and then looking at the Github API documentation (remember that whole thing we were talking about earlier and reading documentation?”

Examples

Here are a few examples of how a simple code snippet added to documentation pages can make them much more user friendly.

- Singularity Global Client

- Living Docs

- The Scientific Filesystem

- Singularity Python

- The Experiment Factory

- Research Applications

Your Mission!

if you are publishing software with your work, you are already winning if you use version control. To get you started, I’ve created a living docs repository with some simple examples you can copy for your Github pages. There are instructions in the repository, and the general steps you can take are:

- Add a README.md to explain how to install and use your software. A cartoon or logo makes it more fun.

- Create a folder called "docs" in your repository, and start writing files! In your repository settings you can turn on Github pages, and it will render from this folder to your Github Pages.

- Add the snippet from editable.html to a base template page, or an individual page. Look at the issues API to see all the things that you can do!

Do you want help? Reach out to me, or StanfordCompute and we will help you with your living documentation, in the name of reproducible, fun, and (beautiful) science! Document on, friends!

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Living Documentation." @vsoch (blog), 27 Feb 2018, https://vsoch.github.io/2018/interactive-posts/ (accessed 01 Jul 25).