Learning a new programming language is magic. Since it’s such a rare experience, I want to document it. If you are looking for useful software, stop reading. This post is about “Salad Fork!”

What motivates someone to learn?

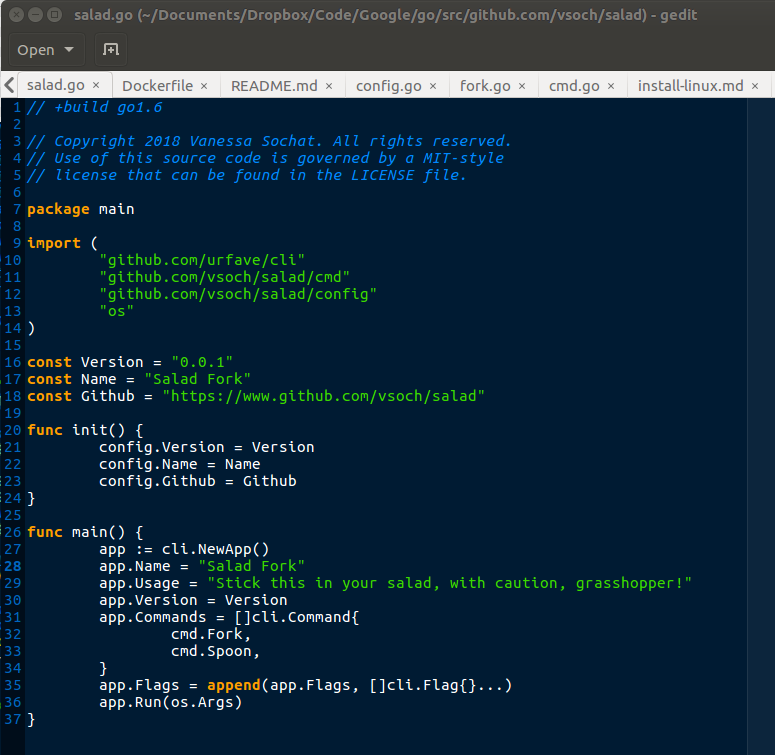

There is a huge catalyst needed to start the chemical reaction of “Want to learn an entire new language!” This catalyst is our underlying motivation that powers us through tricky bugs and sometimes not getting the answer right away. The worst motivation would probably be needing to learn it because it’s required for your job, because then you have added expectation. My most common catalyst is seeing repeatedly awesome things that I must figure out how to do too. I will immediately fall in love with any language that looks beautiful when rendered in a simple text editor (e.g., gedit is my main other than vim). Here is some goLang in gedit:

It’s beautiful. I could stare that that all day. And I do :)

How do I learn a new programming language?

I don’t learn well from guides or tutorials, because I’m not usually interested in what they are trying to do. I only can get heavily invested when I have a very specific (typically useless) goal of making something fun. This goal determines how I start. For example, this last week one of my colleagues made a repository called “salad” with nothing written in the README other than something akin to, “If your fork this repo you have a salad.” It was brilliant. I had to create something silly and lovely to match it. Our lesson here is:

Make something fun that you are genuinely excited about.

My idea was a command line generator of forks paired with puns. I could do this easily in Python, but definitely not Go. With this idea, I could scope my goal to be to produce a command line client of some flavor. And here we start the journey! If you don’t care about the journey, then just check out the work in progress [WIP}. There is much more to come, and I have to figure it out as I go (ha, pun!).

Learning Go

This post reflects only a few days of work, and some on an airplane drifting in and out of sleep. None of it is likely to be wisdom, and I’d bet some is just wrong. It’s purpose is to reflect on my learning. I will also note that before this small project, I had done the simple things to install Go and run the hello world example, although I never delved into anything challenging because I had not found “my motivating project.”

Day One

On day one of my motivating project, most of Go looked like Perl (or any other language that I haven’t done for 10+ years), and maybe I could readily identify for-loops and if statements. I wasn’t even used to the idea of (a declarative language?) where you have to actually declare the variables and their types before using them. Python just doesn’t care about these things! My first 30 minutes or so of learning was passive. It was spent after a dinner browsing through other people’s code. This is how I’ve learned not everything, but a good chunk of programming, because when you look at enough examples you start to see subtle patterns in programming design emerge. I’m not even sure all of them are easy to articulate. To start I finally found a simple entry point example script and used that as a template. And here we have a good piece of wisdom:

Use a simple example as a template to start. First customize, then extend it.

From this simple method I created an (almost equivalent) entry point, but with my own functions. My first finished script, which I also created a Dockerfile for, was one executable called fork.go, and it included all the functions to select a fork and a pun randomly. The first version looked like this.

Day Two

Including Data

One interesting thing I learned is that package data is more challenging to implement. There is no guarantee the executable will be in the same relative spot, unlike python that maintains it’s nice little structure in site-packages. But this made me realize something:

constraints in a language or framework make you a better programmer.

In truth, I had never thought about the size of the modules (e.g. data packaged with Python modules) that I added. I just added them and went on. For the first time, a simple constraint had me asking this question! I really liked that.

But I still needed a solution to have even a simple data structure! As a work around, While I think there are packages that compile the data into the binary, I decided to just create the data (in my case, ascii of forks and spoons, and lists of puns) in the scripts. This seems reasonable for most applications, unless of course you have really huge data to include. For big scientific data, you can provide it as a variable path at runtime. For data that must be packaged, I could imagine creating a predictable application cache, and having an install routine to create it and download the “beeeeeg” data there.

Package Names

I had no idea how the scripts in any given folder related to one another, or what they compiled into. I observed that there can be any number of “go” scripts in the top level folder, packages tended to be flat, and the line at the top that declares a package, if it’s the one called “main,” tells us that script is the executable entry point. The rest of the files must be named according to the repository name. For example,

./github.com/vsoch/salad

├── cmd

│ ├── cmd.go

│ ├── fork.go

│ └── spoon.go

├── config

│ └── config.go

├── Dockerfile

└── salad.go

Let’s say that the above salad.go has the top line say package main - this tells us it’s the entrypoint to the application. Since the repository folder is salad we would put all other scripts in the salad namespace (package salad). But on the other hand, if we import a subfolder, we are actually more likely creating a new package! In the above, the scripts cmd.go, fork.go, and spoon.go are in the package cmd. I (think?) that the functions that are defined in those three files are shared between them.

Imports

There are some standard imports that I see a lot (e.g., os,string and fmt) and the rest are assumed to be folders again installed at $GOPATH. One thing I really like is that if I import something and don’t use it, it gives me an error. How I wish Python could do this! I have to go through old scripts and spend inordinate amounts of time doing searches to see if an import appears only once (and I can remove it).

To install a new package you type go get and I would bet doing a go install against a script will (along with compiling the package) download other packages that you don’t have. I would bet there is a more solid install routine (akin to Python’s requirements.txt or setup.py and I’ll stumble on it soon. Overall, I like how the mapping from the repository to the package name and repository is pretty seamless, and how it all lives neatly organized in my $GOPATH.

The other cool thing about this is that we can thus have subfolders in our repository that we add the includes that are, each in themself, akin to submodules in Python. For example:

import (

"os"

"github.com/urfave/cli"

"github.com/vsoch/salad/cmd"

"github.com/vsoch/salad/config"

)

The folders “cmd” and “config” are nice organized folders that are for each of package cmd and config, and just happen to live with the package salad (see the file structure shown previously). In the same way that the top level folder is called salad and the package and main file are called salad, this is also the case with cmd and config.

Strictness

I was terribly sad to learn that Go doesn’t like my four spaces over a single tab. When I format my data, the delimiter of choice is tab. Here is how I formatted a file:

go fmt salad.go

I would bet you there are editors (or more properly, IDEs) that will do this automatically for you. I’m sticking with gedit and vim, I can’t stand IDEs, but that’s another story! I think I can live with using tabs.

There are some other checks that are done that, while they ensure better programming, I feel like a lot of developers will just come up with hacks to silence them. For example:

if color != "" {

if val, ok := colors[color]; ok {

return colors[color]

}

}

I was OK with this. I was checking if an argument was an empty string, and if it wasn’t, I was checking to see if it was a key in the colors map (a map is a dictionary, for all those Python users). If ok evaluates to true, then the previous ok evaluates to true, and the val is the value. Go got angry at me that I didn’t use “val” always. So then I thought, “Well, then I’ll use it! And I’ll put it nowhere.” I did this:

if color != "" {

if val, ok := colors[color]; ok {

return colors[color]

} else {

_ = val // declared and not used error

}

}

But then I had the (obvious) epiphany, “Why didn’t I just put it nowhere to begin with?” Derp. I tried this:

if color != "" {

if _, ok := colors[color]; ok {

return colors[color]

}

}

Hey, I think I just wrote nicer code! This is another example of why constraints are sometimes good.

Using the simple algorithm of 1. Wanting to do something, and 2. Hacking around until I figure it out, I was able to add different modules for each of fork and spoon, colors, and a simple command line parsing of arguments (largely done by a nice package). Next, I think I’m going to make it serve a simple utensil pun API, because I’ve heard that is one of the strengths of the language. Here it is!

After Day 2

I largely still have no idea what is going on, but I’m starting to recognize patterns. The more I look at scripts with Go, the more I’m able to understand what things mean, and understand the logic of a particular design that I find. The most magical of moments (which can take anywhere from 6 months to 5 years) happens when I can just open up a text editor, start typing, and it’s akin to writing this post. I can’t say when I’ll get there, but I’ll have fun on the journey!

Anyway, if you want to check out the most recent ridiculous thing, just use Docker.

# Random Fork Pun

docker run vanessa/salad

# Random Spoon Pun

docker run vanessa/salad spoon

# Your Wisdom Added

docker run vanessa/salad spoon --message "All hail, the allmighty dish-washer!"

# Control the color

docker run vanessa/salad fork --color cyan

Time to work on other things, don’t forget your Salad Fork, friends!

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Learning GoLang." @vsoch (blog), 02 Feb 2018, https://vsoch.github.io/2018/learning-go/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).