Hey research software engineers! How often might a user trigger a bug in your Python software and not tell you about it? Or how often is a bug triggered but not enough information is provided about it?

Who is Responsible?

We shouldn’t place the burden on collecting and submission of information on the user - they already have their own research and domain of knowledge to worry about. Instead, we should make it really easy for them. We should make it so that, when they are using our software and trigger a bug, we do the heavy lifting to report it.

Remember HelpMe?

A few years back I created the HelpMe software, which is a command line tool that would help a user to interactively submit a bug report. It might look like this:

helpme github rseng/github-support

The above line would collect a title, description, and optionally environment and asciinema screen recording to post an issue at rseng/github-support. HelpMe also supports discourse, uservoice, and any other client that you might want that has an API to post to. But it stopped there - the issue would be opened and that’s it. But what if we could automate it, and (even better) create a database of issues? A discussion was picked up on the datalad issue board around this exact idea.

What do We Need?

We need a version controlled and automated issue reporting system that can either create the entire issue on behalf of the user (given a GitHub token), or a more interactive version that opens up a pre-populated issue report and allows the user to provide additional context. Specifically, I would want the following:

- the user triggers a bug

- the traceback of the error is automatically collected, and a GitHub issue opened with context

- the user can preview and add additional detail to the issue

- the issue is assigned an identifier based on a hash of some metadata you've provided

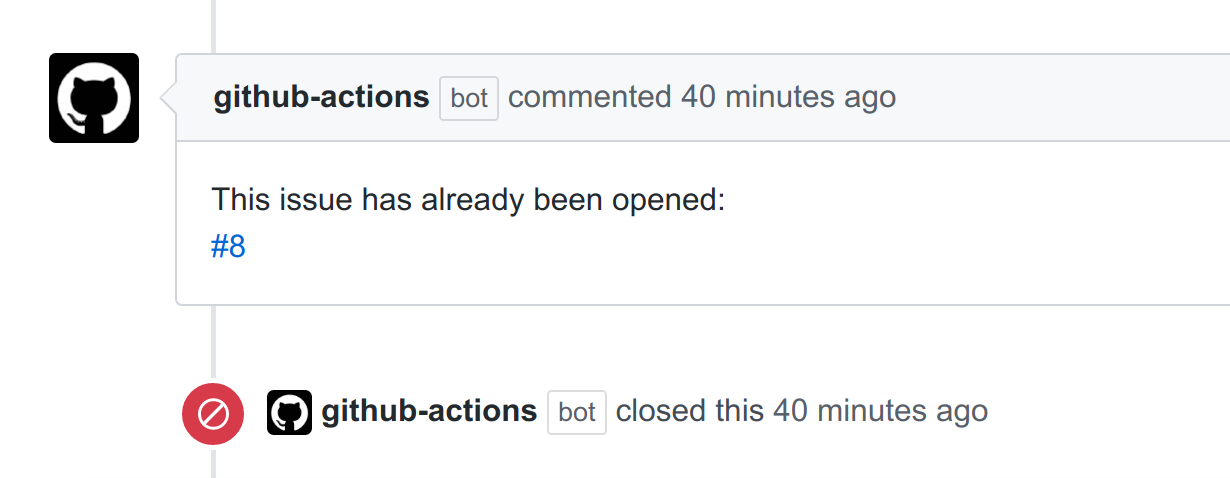

- a GitHub workflow will direct the user to another issue (if was previously reported) and close the current issue

- the metadata about the error is pushed to a support repository that serves as a flat file database.

And then the errors database can be used to derive insights about your software.

An Example

To drive this functionality, I’ve published version 0.0.40 of helpme that provides a headless submission workflow, and created an example repository rseng/github-support that uses it. A side-note: this new organization rseng is intended to be an open community of research software engineers that want to collaborate on fun projects (such as this one!) so if you’d like to join, please let me know and I’ll send an invite!

rseng/github-support

This post introduces the idea of a

GitHub support repository

A GitHub support repository is one that solely exists for providing user support for some software. The content of the repository is a database of error reports, organized and updated by identifiers that can uniquely identify the issues. Within the repository, an example.py script shows how the issue is generated and submit, along with a workflow that will trigger on newly opened issues, parse the issue body, and then determine based on the identifier and current issues database if the issue has already been opened. In the case that the issue was previously opened, the body is still saved, but a comment is added to the newly opened issue to alert the user, link to the previous issue, and then the issue is closed.

If you look at the repository itself, issues are organized under an “issues” folder, and then an identifier subfolder, which is derived from the exception thrown and message.

How does it work?

It comes down to importing the helper, and then running the function when you want the issue to be reported, and including a meaningful identifier, title, and body. In the example below, we don’t require a GitHub token, so the user will be given a url to open to (or if on a desktop, the window will be opened). We turn off confirmation of the whitelisted environment variables since we know the defaults don’t include anything secret.

from helpme.main import get_helper

helper = get_helper("github", confirm=False)

helper.run_headless(

identifier=identifier,

title=message,

body=body,

repo="rseng/github-support",

)

Not shown is placing this in the context of an error, or deriving a meaningful identifier, title, or body. Specifically, if you look at the more substantial example.py, you’ll see that:

- we triggers an import error, and create a helpme GitHub helper

- the error message and type is used for the identifier (converted to an md5 hash by helpme)

- a browser window opens for the user to add details to the error in a GitHub issue.

- a GitHub workflow parses the new issue to add it's metadata to the database

- the user is alerted and the issue closed if the issue has already been opened

- the database is updated

If you intend to use this helper throughout your library, it’s recommended to write a function as we’ve done in the example. The structure is of course up to you, and in fact, all of the steps from the metadata included, how the identifier is derived, and how the GitHub issue is parsed, are totally up to you. Let’s talk about some of these decisions next.

Questions to Think About

What should I use for an identifier?

The level of detail that you want to include with your string identifier is up to you, but you should be consistent as changes would change the database structure. For example, you might be happy including the calling module relative path and the error message, but not want to include the software version so that an error that reports the same message and location (across versions) is considered the same. On the other hand, you might want to add a level of nesting to folder organization of your issues database to take versions into account. For example:

issues/

0.0.1/

md5.5fddcd18252717a7a11c494d24b16d4e/

8.md

0.0.2/

md5.5fddcd18252717a7a11c494d24b16d4e

10.md

The above structure would suggest that the same issue (based on the identifier) was found across two versions of software. On the other hand, if version is not important to you, you might have this instead:

issues/

md5.5fddcd18252717a7a11c494d24b16d4e

8.md

10.md

You would want to provide whatever metadata is needed by the issue parser into the helpme body, and then have the GitHub workflow parse it to derive the desired organization. This structure isn’t implemented or enforced by helpme, but rather provided as a starting example.

How should you structure the data?

A GitHub repository isn’t a real database, but we can sort of think of it as a flat file database, and in this dummy example I chose to use markdown so that it would render the issue content easily. In that even the largest repositories have a few thousand issues, having a few thousand small files is very reasonable for keeping in GitHub. You could dump into markdown anticipating some future processing as I’ve done here, but likely you’d do better to provide structured metadata, and then parse into a data format like json or yaml. If you do choose one of these formats, make sure to validate your generated files for correctness in the workflow.

How should you organize the data?

The example takes a simple approach of creating an “issues” folder at the root of the repository, and then naming subfolders based on identifier hashes. The issues are named according to numbers within, meaning that you can quickly parse over files (and sort) to find the first opened issue for any particular identifier, or you can quickly count the files to get the number opened for the identifier. There is no reason you need to organize your data in this fashion - I took an approach to limit each issue to one file to not have any “GitHub race” conditions, or two opened issues trying to edit the same file at once that might hold some summary information.

Should you use your software repository?

While your issues might be directed to your software repository, the issues database doesn’t necessarily need to be, and I would recommend keeping the two separate. This example repository uses the same repository for the content (examples, etc.) and database so the entire package can be cloned and easily understood. You would basically want to update the parse_issue.py and report_issue workflow to clone and update another repository with issues.

How automated do you want it?

Depending on how you instantiate the helper, you can require the user to export a HELPME_GITHUB_TOKEN

helper = get_helper('github', require_token=True)

and ensure that the issue posts are completely programmatic. If you don’t require a token, the URL will be printed to the terminal, and a window opened (in the case of having a desktop). For either approach, you can also skip the verification of the whitelisted environment variables:

helper = get_helper('github', confirm=False)

and in fact it would make sense to do this for a totally automated submission:

helper = get_helper('github', require_token=True, confirm=False)

Questions?

I hope that this small library can be helpful to Python maintainers that want a little more automated error reporting. The only moduled required for this base GitHub interaction is requests, and additional support for asciinema, uservoice, or discourse can be installed if desired, e.g.,:

pip install helpme[discourse]

pip install helpme[asciinema]

pip install helpme[uservoice]

Would you like help to write a custom workflow? Please open an issue and I’d be happy to help. We are going to be writing an integration with datalad, and I’m excited! If you want more examples of arguments and usage of helpme, see the GitHub headless docs. And if you are a research software engineer that wants to join the rseng community to collaborate on projects, please also send me a note.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Automated GitHub Support for Python Packages." @vsoch (blog), 17 Dec 2019, https://vsoch.github.io/2019/helpme-headless/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).