What kind of headers are hiding amongst our favorite websites? Since we had a day off for Memorial Day, I started off by finishing editing a podcast episode, but for the rest of the day wanted to do something entirely useless and fun. Inspired by this post I decided to do a quick project to explore the space of url headers. This was messy and quick, but I wanted to do the following:

- Come up with some long list of urls

- For each url, extract header responses and cookie names

- Save data to file to parse into an interactive web interface

And then of course once I had a reasonable start on the above, this escalated quickly to include:

- A Dockerized version of the application

- A GitHub action to generate the data

- A parser script to export the entire flask site as static

And so this was my adventure for Memorial Day! If you want to just check out the (now static) results pages that was generated for the GitHub action, see here. If you want to use the GitHub action to study your own list of urls, check out instructions on the repository. Otherwise keep reading to learn how I went about this project, and a few interesting things I learned from doing it.

1. Parsing Data

I first started writing a simple script to get headers for 45 sites that are fairly popular,

but ultimately found a list of 500 sites to use instead.

I had to edit the list extensively, as many urls no longer existed, or needed to have

a www. prefix to work, period. I also removed urls that didn’t have a secure connection.

This gave me a total of 500 urls (I added a few to get a nice even number!)

represented in a text file, urls.txt. From those sites (when I parsed from my local machine),

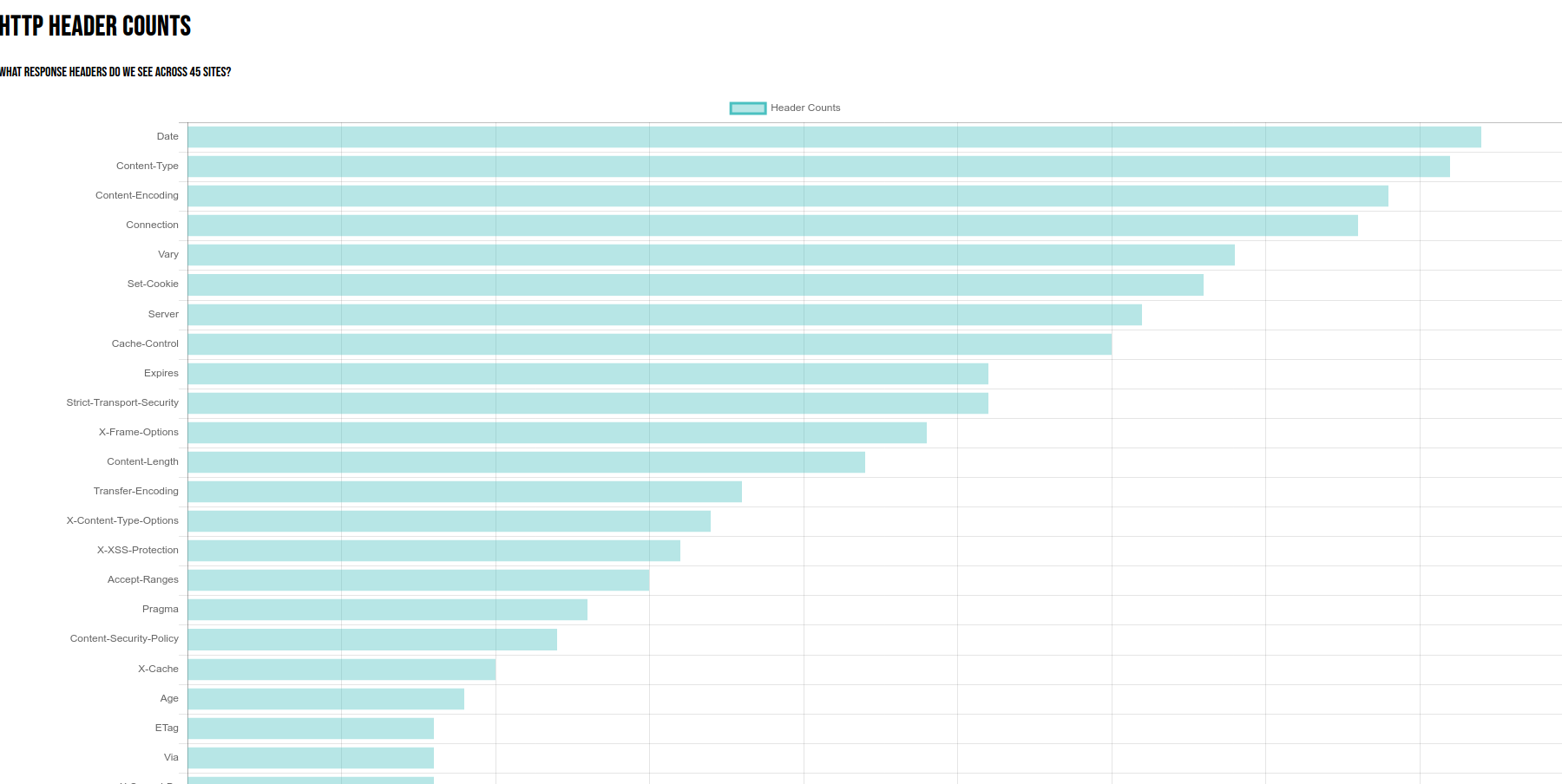

I found 615 unique headers, ranging in frequency from being present in all sites

(Content-Type, N=500) to only being present for one site (N=1). The most frequent was “Content-Type,” followed by Date.

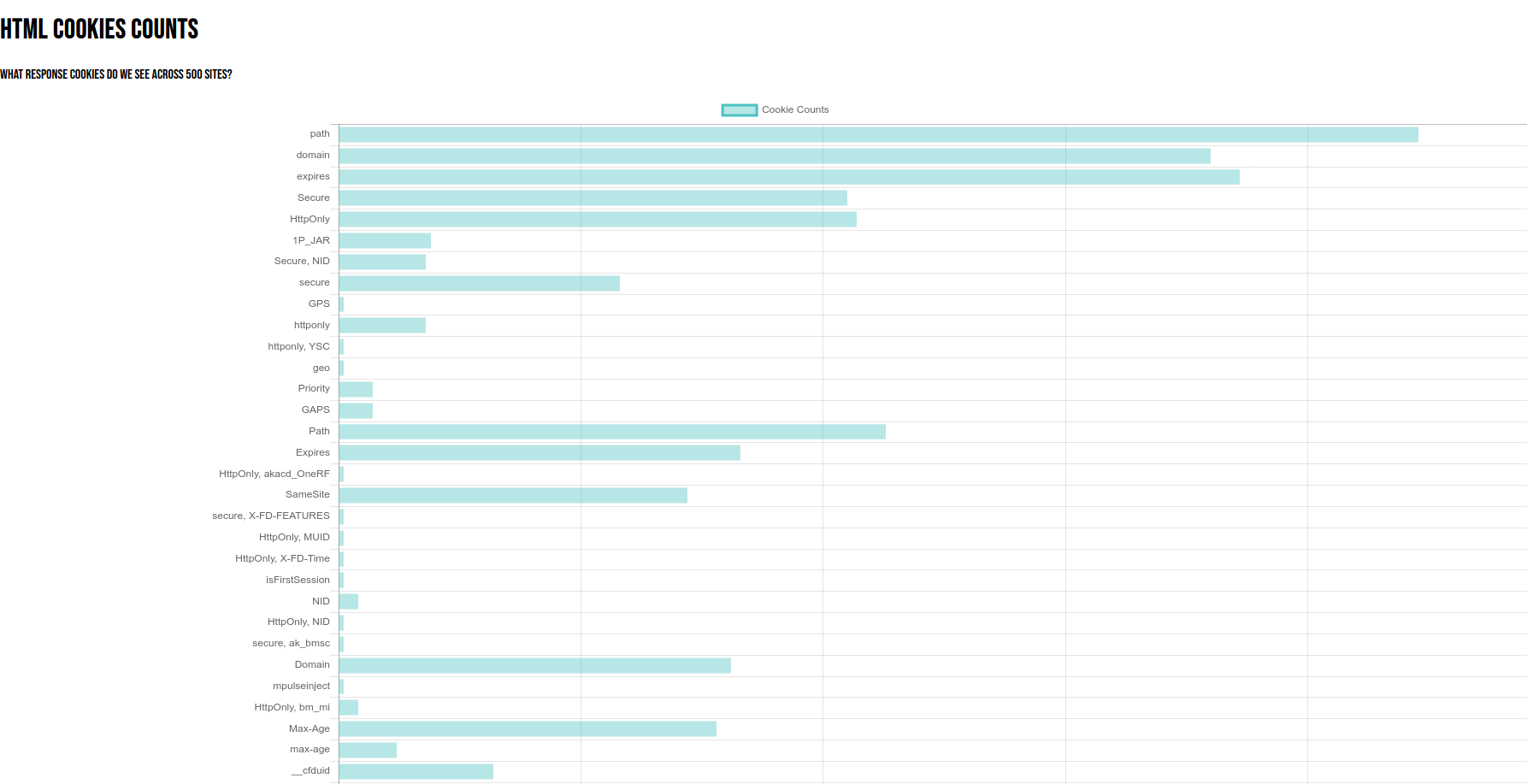

I did this with a run.py script. I also separately parsed cookies, keeping the names but removing values in the case that they had any kind of personal information or could otherwise be used maliciously. I found a total of 457 unique cookies across the 500 sites.

2. Flask Application

I decided to use Flask and ChartJS because they are both relatively easy, and although I’ve recently tried other charting Python libraries, for the most part they have been annoying and error prone. From this I was able to create a main view to show all counts, and table views to show details.

Why are you wasting your time doing this?

I suppose the data exports could be enough, but I think it’s useful to sometimes package analysis scripts with an interactive interface to explore them. Yes, it’s a lot of work, but if you do it a few times, it isn’t hugely challenging and it’s fun to see the final result.

The Interface

Here is the basic interface! The “home” page has a plot of counts. y axis is the header, and the length of the bar represents the number of sites that have it:

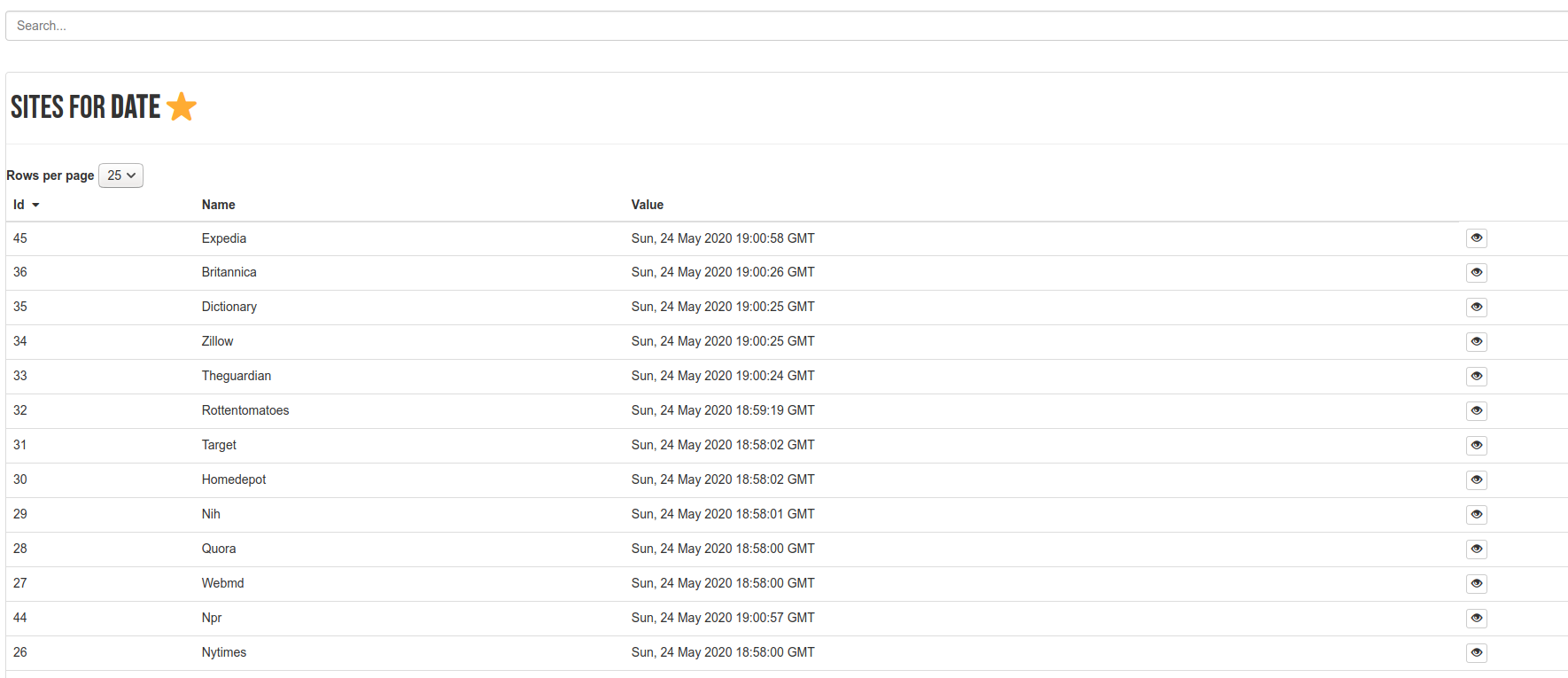

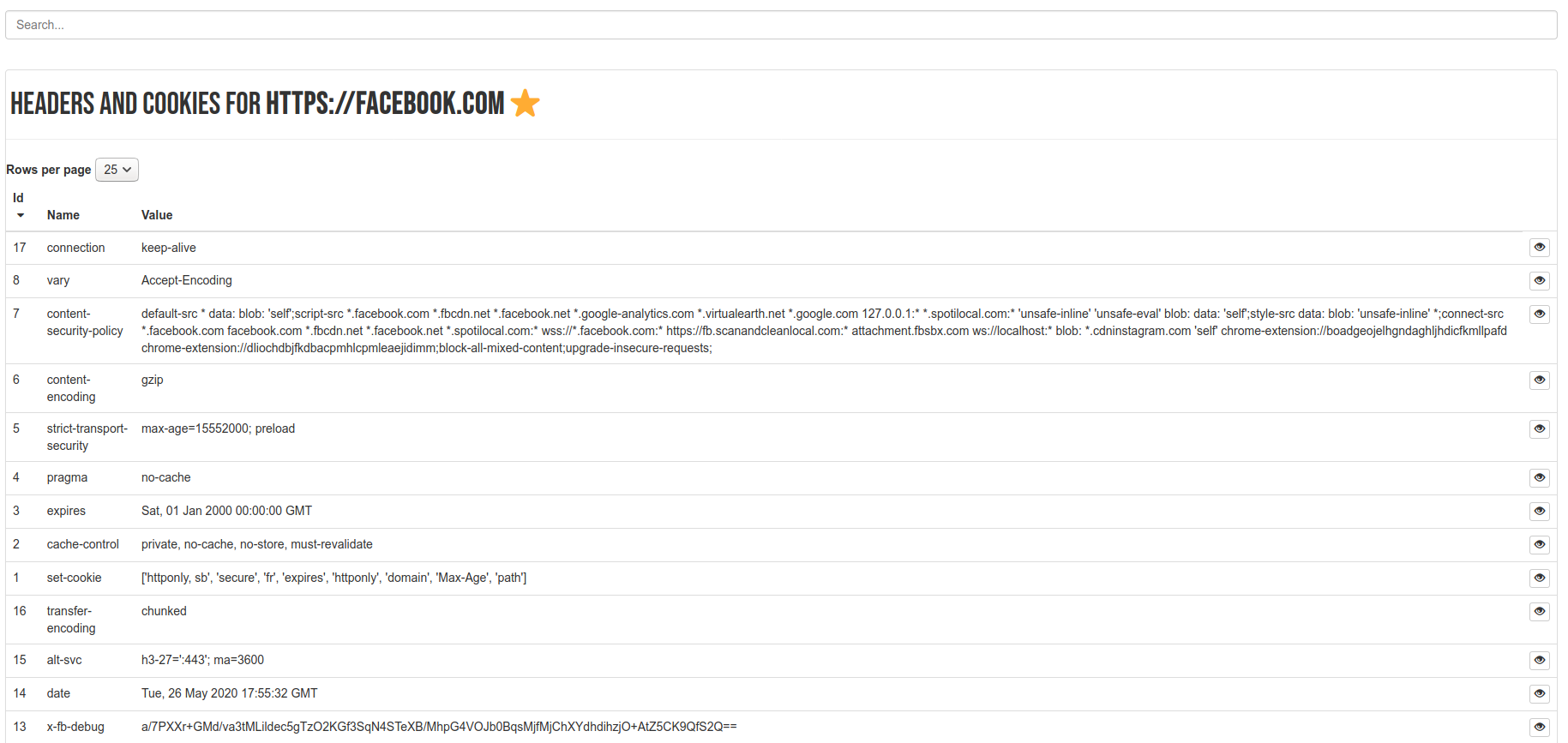

When you click on a header, you are taken to a page that shows values for each header:

Yeah, the Date header isn’t hugely interesting, other than capturing the date

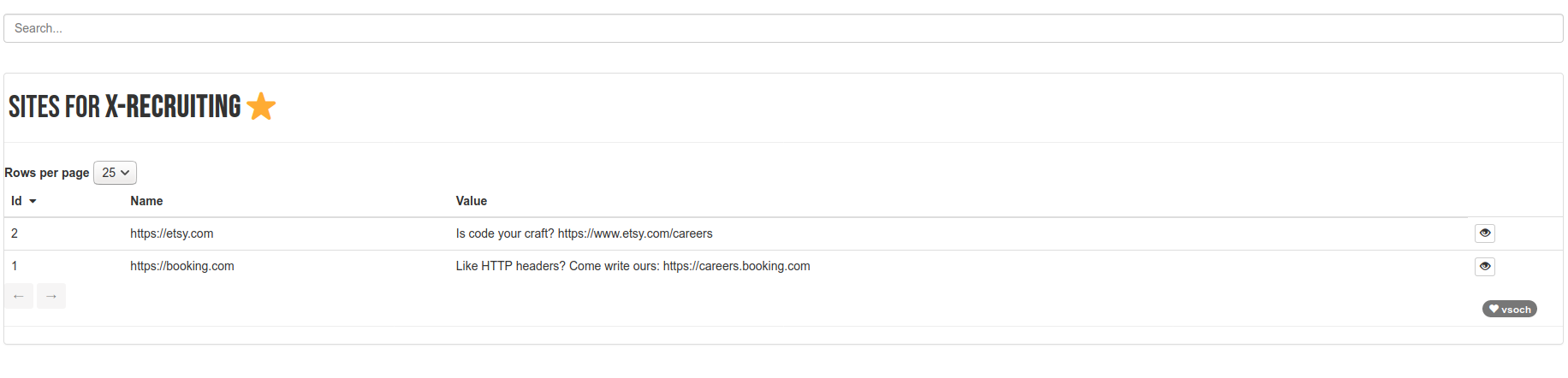

when I made the request! More interesting is the X-Recruiting header, which

I only found present for etsy and booking.com:

This was the header that originally caught my interest, because it seemed so unexpected. If you browse from a header and click on a site, you are taken to it’s summary view. Here is facebook:

And finally, there is an equivalent counts page for cookies:

To run this locally you can do:

$ python app/__init__.py

* Serving Flask app "__init__" (lazy loading)

* Environment: production

WARNING: This is a development server. Do not use it in a production deployment.

Use a production WSGI server instead.

* Debug mode: on

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000/ (Press CTRL+C to quit)

* Restarting with stat

* Debugger is active!

* Debugger PIN: 261-026-821

But you might be better with Docker, discussed next.

3. Dockerize

To be fair, I did develop this locally, but my preference is create a Dockerized version so if/when someone finds it in a few years, they can hopefully reproduce it slightly better than if the Dockerfile wasn’t provided. To build the image:

$ docker build -t vanessa/headers .

And then run it, exposing port 5000:

$ docker run --rm -it -p 5000:5000 vanessa/headers

And you can open to the same http://localhost:5000 to see the site.

Although I didn’t run the interface for the GitHub action, we can use the GitHub

action to generate data, download it as an artifact, and then export a static

interface. These steps are discussed in the last section.

4. Parse Pages

My final goal was to generate completely static files for all views of the app. Why do we want to do this? To share on GitHub pages, of course! I wrote a rather ugly, spaghetti-esche script, parse.py that (given a running server) will extract pages for the cookies, headers, and base sites, and then save them to a static folder “docs” along with a README.md. Once you view the index on GitHub pages, however, you can navigate to pages as you normally would, and this is possible because we added the prefix of the repository (url-headers) to the application.

5. GitHub Action

I then took this a step further and made a custom GitHub action, represented in action.yml and run via entrypoint.sh that handles taking in a user-specified urls file, and running the script to generate data. It then saves it as an artifact, and you can download to your computer to generate the interface. The user of the action can, of course, do anything else they desire with the data outputs. This was the first time I attempted to start a service that used a port on GitHub actions, so you can imagine I ran into some pitfalls, and at the end I realized that I needed to start the flask application as a service container. I decided that 7 hours was long enough to have worked on this, and although it would be great to run the interface and generate static content during the action run, I’m best to try again next time. But I can still share some quick things that I learned! Firstly, you can’t start a sub-shell and then leave it running in the background. This won’t work:

$(gunicorn -b "127.0.0.1:${INPUT_PORT}" app:app --pythonpath .) &

but something like this might be okay, albeit I’m still not sure we could then access this port:

gunicorn -b "127.0.0.1:${INPUT_PORT}" app:app --pythonpath . &

For the first, it threw me off a bit because it exited cleanly without a clear error message, and so I thought that it was the previous script that had run. And actually, there was another issue. See that “INPUT_PORT” variable? The container was exposing 5000, and I was running the server on that port, and logically this is what I’d want to do with Docker to map the port to my local machine. But it seems like with GitHub actions, since you would then be connected to the runner’s port 5000, this leads to an exit. Here is the error that resulted:

Starting server...

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.7/site-packages/urllib3/connection.py", line 160, in _new_conn

(self._dns_host, self.port), self.timeout, **extra_kw

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.7/site-packages/urllib3/util/connection.py", line 84, in create_connection

raise err

File "/usr/local/lib/python3.7/site-packages/urllib3/util/connection.py", line 74, in create_connection

sock.connect(sa)

ConnectionRefusedError: [Errno 111] Connection refused

Doh! Anyway, I never got it fully working, and decided to simplify the action to just produce the data, save as an artifact, and then you can download to your local machine and start the web server and generate the interface. There is a bit of a catch-22 because we would need a service container built after generation of data, and then interacted with from the next step, but the service container has to be defined and started before the step. I’m not sure that GitHub Actions supports this, because most of their examples for services are databases or other tools that don’t require customization or even binds to the host. Anyway, this is something to look at again for some next project.

6. Investigation

Finally, I wanted to spend a few minutes looking into some of the things that I noticed or otherwise learned. This is probably the most interesting bit!

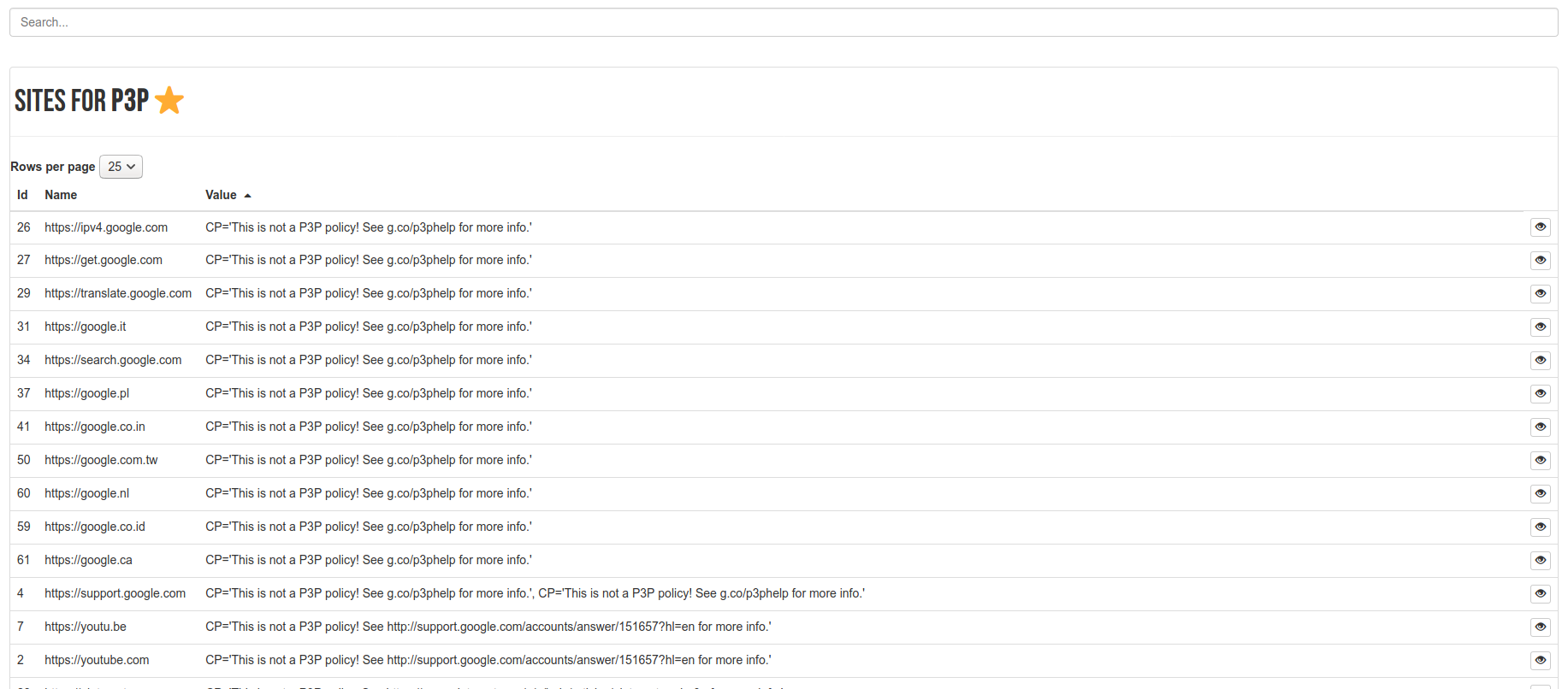

p3p Header

A lot of sites had a p3p header (N=67) but for that set, many of them were invalid!

P3p refers to the Platform for Privacy Preferences (note three Ps). It seems that it was developed in 2001, recommended in 2002, but it’s since obsolete. I suspect many sites still provide it. I think the idea was that the site could define this header to say something about their privacy policy, but it seemed to have some issues. So we are seeing a frament of internet-past!

X-recruiter

As I mentioned above, I found two sites, booking.com and etsy.com, that had the recruting header. So, if you are looking for a job, reach out to them via that! I think the issue with this kind of header is that if word gets out that it exists, it becomes a lot less meaningful because it’s not so hard to find.

Facebook seems to have a debug id x-fb-debug that I suspect their support team uses to some

degree. It’s a long hash of lord knows what.

x-fb-debug EyXfGc3wcZMW8OHdKDbaweUZB1ih9.....................SHUCHayvdvSC2Gxrg==

Their content-security-policy (ref) gives a hint at what resources the site is allowed to load

for any particular page. Do any of these listings bother you (I added newlines for readability)?

default-src * data: blob: 'self';

script-src *.facebook.com *.fbcdn.net *.facebook.net

*.google-analytics.com *.virtualearth.net *.google.com 127.0.0.1:*

*.spotilocal.com:* 'unsafe-inline' 'unsafe-eval' blob: data: 'self';style-src data: blob: 'unsafe-inline'

*;connect-src *.facebook.com facebook.com *.fbcdn.net *.facebook.net

*.spotilocal.com:* wss://*.facebook.com:* https://fb.scanandcleanlocal.com:*

attachment.fbsbx.com ws://localhost:* blob: *.cdninstagram.com 'self'

chrome-extension://boadgeojel...

chrome-extension://dliochdbjfkdb...

The first chrome extension seems to be this one to do some kind of webcast, and the second I’m not sure about, but it’s the last one listed here. What in the world?

Yeah, there are chrome extensions in there along with… my localhost? So I suspect Facebook has permission to scan my localhost for something? Even more troubling is “ws://localhost:*”.

Server

I was curious to see what kind of servers the sites (at least reported) to use. I fwopped off the version strings to get a sense. The winner seems to be nginx, which I’m fairly happy about, because it’s definitely my favorite! Apache comes in at a close second, and then providers like cloudflare and google web services (gws?)

{'nginx': 116,

'apache': 67,

'cloudflare': 38,

'gws': 19,

'ats': 13,

'server': 12,

'openresty': 12,

'gse': 11,

'sffe': 10,

'microsoft-iis': 7,

'esf': 5,

'google frontend': 3,

'amazons3': 3,

'youtube frontend proxy': 2,

'github.com': 2,

'vk': 2,

'mw1320.eqiad.wmnet': 2,

'tengine': 2,

'ebay-proxy-server': 2,

'tsa_a': 2,

'akamainetstorage': 2,

'mw1329.eqiad.wmnet': 2,

'envoy': 2,

'qrator': 2,

'ecd (aga': 2,

'support-content-ui': 1,

'mw1319.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'europa': 1,

'bbc-gtm': 1,

'mw1264.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'mw1275.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'marrakesh 1.16.6': 1,

'dms': 1,

'rhino-core-shield': 1,

'ofe': 1,

'apache tomcat': 1,

'http server (unknown)': 1,

'mw1371.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'litespeed': 1,

'am': 1,

'cloudflare-nginx': 1,

'mw1370.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'squid': 1,

'httpd': 1,

'mw1321.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'dtk10': 1,

'pepyaka': 1,

'oscar platform 0.366.0': 1,

'myracloud': 1,

'566': 1,

'mw1333.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'nq_website_core-prod-release e1fc279e-1c88-4735-bc26-d1e65243676d': 1,

'nws': 1,

'gunicorn': 1,

'mw1327.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'apache-coyote': 1,

'ask.fm web service': 1,

'cat factory 1.0': 1,

'ecs (dna': 1,

'ia web server': 1,

'ecacc (dna': 1,

'kestrel': 1,

'mw1266.eqiad.wmnet': 1,

'api-gateway': 1,

'istio-envoy': 1,

'smart': 1,

'uploadserver': 1,

'envoy-iad': 1,

'zoom': 1,

'artisanal bits': 1,

'rocket': 1

}

But of course this is only a subset of the sites reporting their servers, 386 to be exact:

sum(server_counts.values())

Powered By

What about the “powered by” header? It was only present for 55 of the sites, but I figured I wanted to take a look:

{

"PHP": 21,

"Express": 13,

"WordPress": 5,

"ASP.NET": 4,

"ARR": 2,

"Fenrir": 1,

"Brightspot": 1,

"Element": 1,

"Victors": 1,

"WP Engine": 1,

"shci_v1.13": 1,

"Lovestack Edition": 1,

"HubSpot": 1,

"Nessie": 1

}

Wow, that many PHP? and Wordpress? What in the world is Lovestack Edition?

Number of Headers

I was browsing the sites, and realized that a china-based site only had 8 headers! This seemed small compared to the over 25 that I had seen for some. I was then curious to know, which sites have the most headers? I’ll show you the top and bottom here. I was a bit surprised that history.com was at the top, because I was expecting some advertising company. :)

{

"https://history.com": 32,

"https://princeton.edu": 31,

"https://gizmodo.com": 31,

"https://inc.com": 31,

"https://wired.com": 30,

"https://forbes.com": 29,

"https://nature.com": 29,

"https://newyorker.com": 29,

"https://www.docusign.com": 29,

"https://www.fastly.com": 29,

"https://istockphoto.com": 28,

"https://vox.com": 28,

"https://theverge.com": 28,

"https://utexas.edu": 28,

"https://vimeo.com": 27,

"https://nytimes.com": 27,

"https://slideshare.net": 27,

"https://yelp.com": 27,

"https://psychologytoday.com": 27,

"https://nokia.com": 27,

"https://airbnb.com": 27,

"https://upenn.edu": 27,

"https://gitlab.com": 27,

"https://bbc.com": 26,

"https://nih.gov": 26,

"https://harvard.edu": 26,

"https://yale.edu": 26,

"https://oracle.com": 26,

"https://unicef.org": 26,

"https://usgs.gov": 26,

"https://www.docker.com": 26,

...

"https://about.me": 10,

"https://europa.eu": 9,

"https://line.me": 9,

"https://issuu.com": 9,

"https://qq.com": 9,

"https://detik.com": 9,

"https://washington.edu": 9,

"https://rt.com": 9,

"https://t.co": 9,

"https://nginx.org": 9,

"https://4shared.com": 9,

"https://googleblog.com": 9,

"https://iso.org": 9,

"https://ucoz.ru": 9,

"https://www.discourse.org": 9,

"https://archive.org": 8,

"https://hatena.ne.jp": 8,

"https://amzn.to": 8,

"https://chinadaily.com.cn": 8,

"https://rediff.com": 8,

"https://sputniknews.com": 8,

"https://rakuten.co.jp": 7

}

I’d be interested to know if different countries have different rules regarding these headers, and if we could see that in the data. For fun, let’s inspect history.com and see what the heck all those headers are. I wasn’t super happy to see “aetn-“ prefixed headers that seemed to capture my location information.

aetn_backend fastlyshield--shield_cache_bwi5125_BWI

aetn-web-platform webcenter

aetn-watch-platform false

aetn-state-code XXX

aetn-postal-code XXX

aetn-longitude XXX

aetn-latitude XXX

aetn-eu N

aetn-device DESKTOP

aetn-country-name united states

aetn-country-code US

aetn-continent-code NA

aetn-city XXX

aetn-area-code XXX

You see, I didn’t explicitly provide anything. I’m not sure what these headers are, because my Google searches failed me. Does anyone know?

Random Headers of Interest

etag

The etag header tracks a specific version of a resource. This gives us a crazy level of detail if we wanted to reproduce some web scraping thing exactly. Of course we would run into trouble if the e-tag turned out to mismatch. Even the wayback machine can’t help us now!

Link

The link header appears to contain actual link attributes, and they represent alternative addresses. For example, docker.com has:

docker.com/>; rel='shortlink', docker.com/>; rel='canonical', docker.com/index.html>; rel='revision'

Overall

I had so much fun with this small exercise! I think it’s important for research software engineers to think beyond the code, and consider:

- Have I made this tool easy to reproduce and customize?

- Have I made it easy to automate?

- Can the researcher visualize a result?

For any kind of tool that involves data, although I don’t do a ton of work in the space, I’m a strong proponent of the idea that the software should make it easy not only to “run the thing” but also to share and interact with outputs. But I understand, maybe not everyone wants to spend their free time writing Javascript. I appropriately stumbled on a Tweet this weekend that summarizes my 4 day weekend well:

I’ve always hated it when people ask me “What do you do for fun?” because I do the exact same things that I would do when I’m working, albeit the “useless factor” is hugely amped. So that was my weekend. This was a fun exercise, but it made me more anxious about the kind of information being collected in my browser. I hope that there is more discussion around these issues - How can this data be more transparent? What kind of control do we have for these headers anyway? Heck, this is only for a single get request for a static file. I don’t even want to imagine what kind of javascript is being run when I navigate to a site. I suspect all my local ports are being scanned, for servers or otherwise. Oy vey. What can we do?

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Parsing Headers." @vsoch (blog), 25 May 2020, https://vsoch.github.io/2020/url-headers/ (accessed 01 Jul 25).