In a continued effort to make build, test, deploy, and introspection of containers as easy as possible, today I’d like to share a small project that I’m really excited about - the containershare. The containershare combines Github (version control) with CircleCI (testing), Docker Hub (deployment) and Github Pages (documentation) to make it easy to share not only containers, but full metadata and introspection of what’s inside! I wanted this to be stupid and easy - for you to fork a Github repository, make a few setup clicks in these free for use services, and to have everything you need for reproducible science. The magic behind this is continuous integration, or a service like CircleCI that gives you a server to run almost anything you can dream of! It happens on Github pushes! It deploys to #alltheplaces!

Let’s get excited about continuous integration!

I am so excited about continuous integration. And I’ve built some tools to get you started easily. Let’s discuss! If you want to quickly jump to a section, this post discusses:

- Overview of Containershare including screen shots, and high level description

- Use Cases such as academic resource and experimental paradigm libraries

- Background some awesome notes on CircleCI recipes, and how it works

- Future Development that you should expect, because it’s in the works!

And for instructions on deploying your own containershare, contributing a container, or using one, see the containershare repository. Let’s start with an overview.

Containershare

Containershare is a distributed, open source and customizable container registry. But you don’t need a physical or any paid services to deploy or use it. That means that you deploy it, freely, using all openly available and free online tools. You are empowered to submit containers to a containershare registry, to deploy your own, and customize any and all of the integrations, build steps, documentation, or other. Nothing is mysterious because all of the code is available for you to see, change, and customize for your needs. Here is what it comes down to:

- You add a continuous integration template that could be for a Docker repository, or jupyter notebook.

- You push to Github and connect CircleCI and Docker Hub

- The container is built, deployed to Docker Hub, and manifests are pushed **back** to Github pages

- You submit a pull request with a simple text file to your containershare repository, and it's tested for the metadata and added

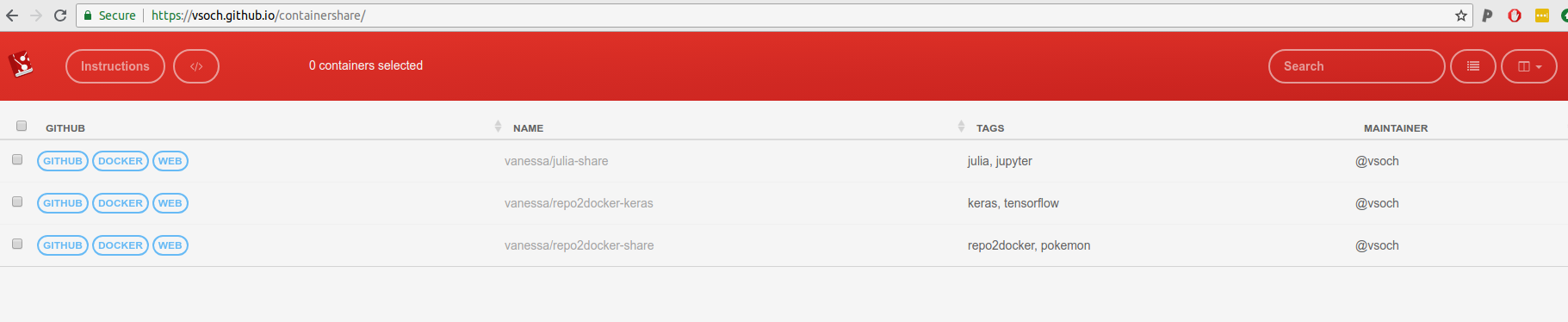

What does this look like, actually? Well you share your table of containers with your users:

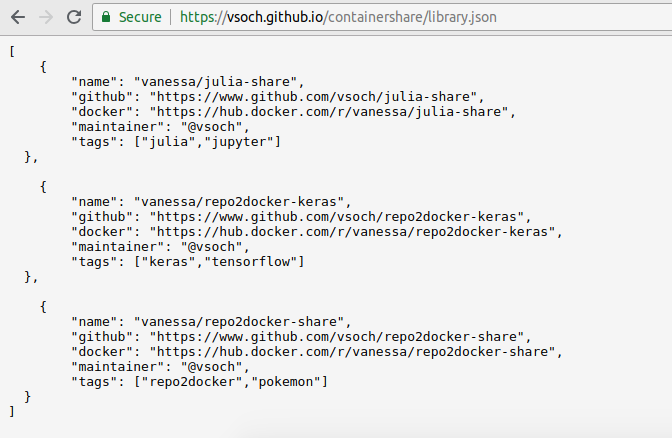

There’s also an API that will serve the basic table as JSON, available for any containershare repository at the Github Pages address associated with the repository. For example: https://vsoch.github.io/containershare/library.json.

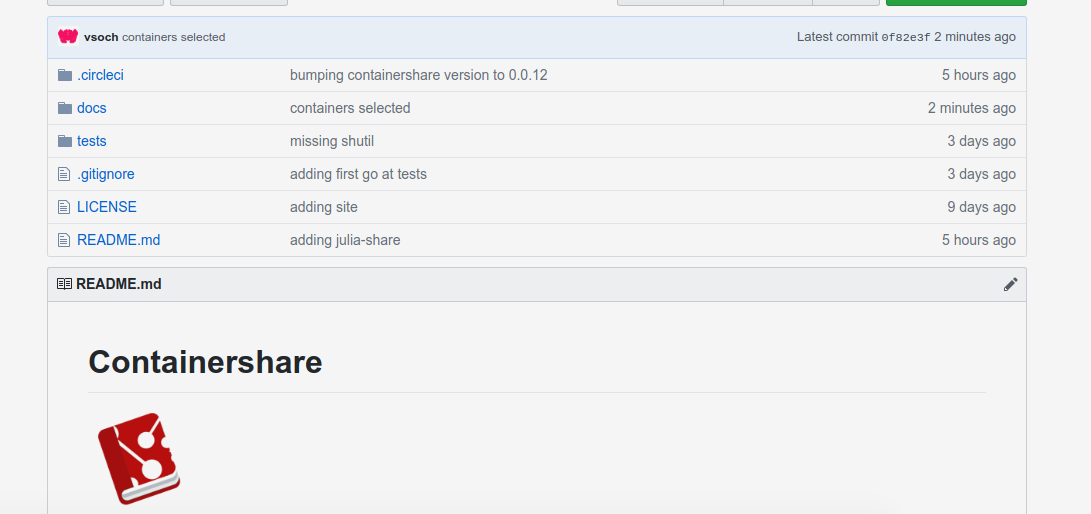

And by the way, these web pages are generated automatically when you push to Github, deployed in the local “docs” folder of the repository:

Contributing a Container

Let’s say that I have a containershare of psychology experiment paradigms, and I want to contribute my container to some containershare. What does this mean? It means writing a text file, and issuing a pull request to the repository. That’s is! The textfile looks like this:

---

layout: null

name: "vanessa/julia-share"

maintainer: "@vsoch"

github: "https://www.github.com/vsoch/julia-share"

docker: "https://hub.docker.com/r/vanessa/julia-share"

web: "https://vsoch.github.io/julia-share"

uid: "julia-share"

tags:

- julia

- jupyter

---

It’s very simple - it includes links to metadata, and some tags for the table.

Container Introspection

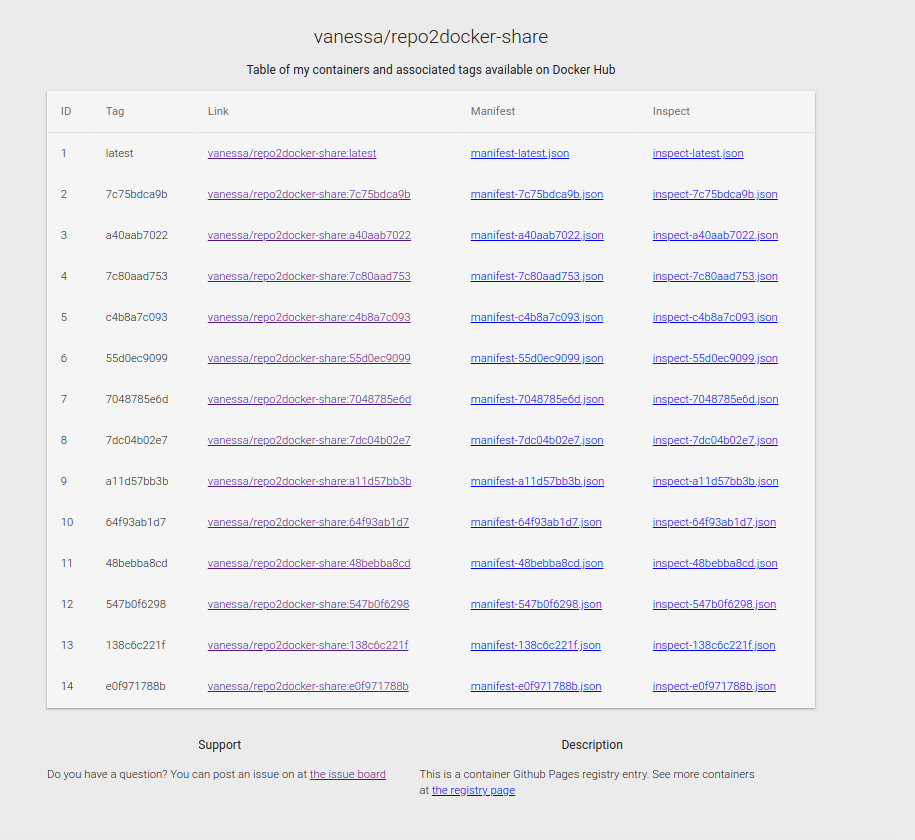

Why do we want these links? Because they are provided in the container, always, to link to the Github Pages deployed by the contributed

repository. For example, here is the Github pages for the repo2docker-share container:

If I go to the tags.json endpoint (https://vsoch.github.io/repo2docker-share/tags.json), I can programmatically get the latest list of tags, generated automatically, and each tag coinciding with the first 10 characters of a Github commit. This means I can trace the stage of my repository container with each built container and metadata for it:

latest

7c75bdca9b

a40aab7022

7c80aad753

c4b8a7c093

55d0ec9099

7048785e6d

7dc04b02e7

a11d57bb3b

64f93ab1d7

48bebba8cd

547b0f6298

138c6c221f

e0f971788b

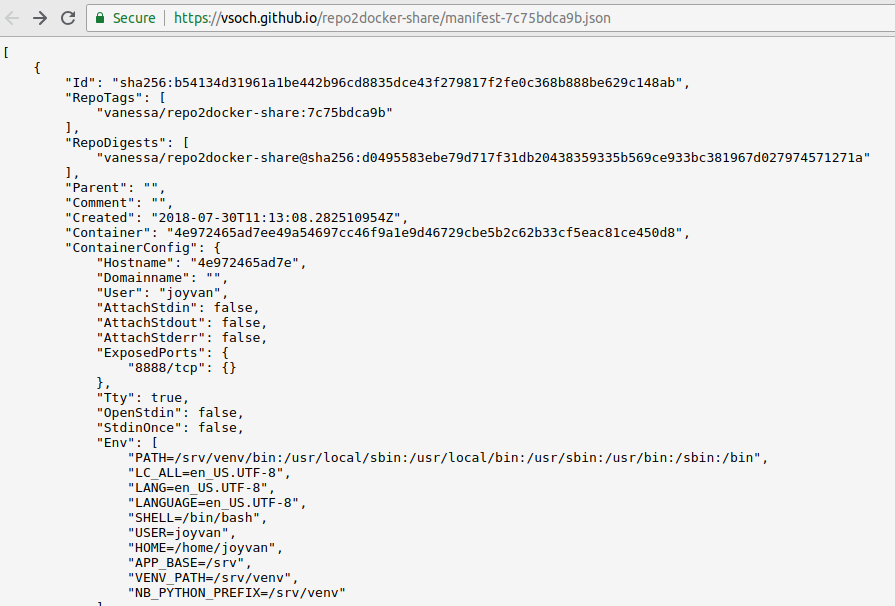

What about metadata? Well for each tag, I get a full manifest.json and container inspection via inspect.json. Here is the manifest. Yes, it’s your bread and butter Docker manifest.

Let there be metadata!

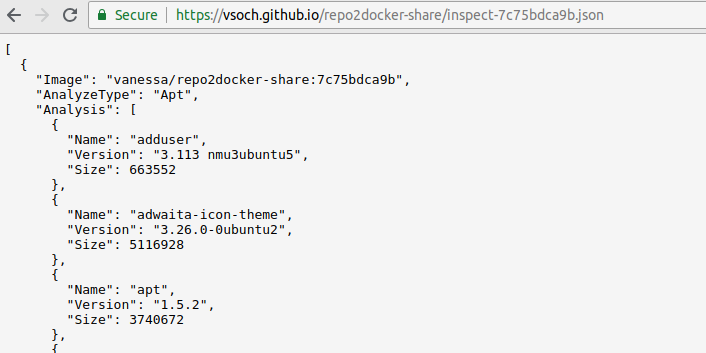

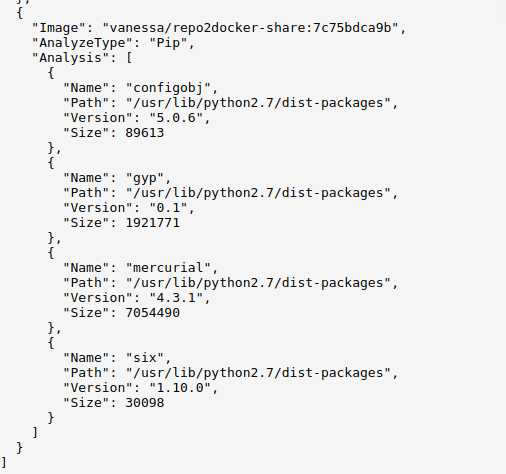

By using Google’s Container Diff tool, I have:

packages and their versions

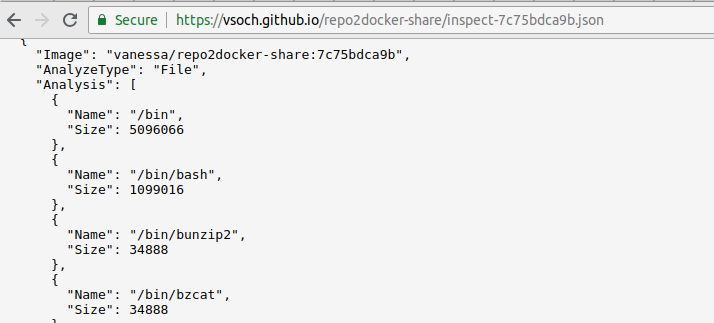

files and sizes

A complete list of files and their associated sizes. Every. Single. One.

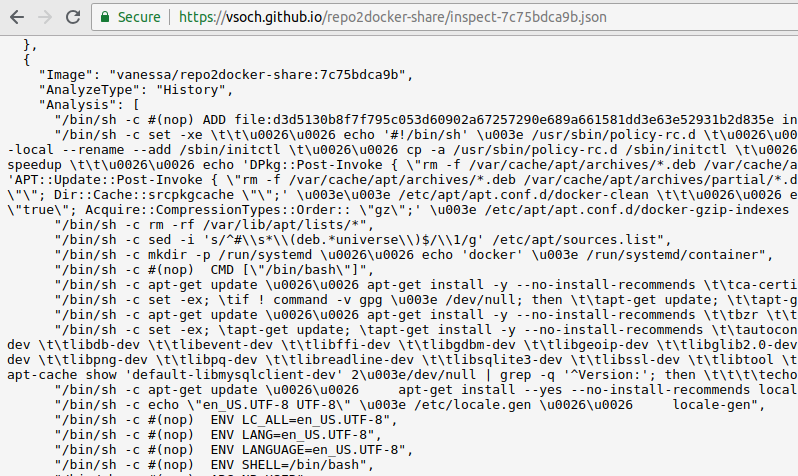

history

and finally…

pip (python package manager)

You don’t need to think about how to create or share any of this - it happens when you use the templates. This means that, whether you want to contribute a container to a containershare, deploy your own, or just use one to discover (and inspect) containers, it always comes down to just forking a Github repository, and then clicking some buttons in a web interface to connect to services like Github Pages, Docker Hub, and CircleCI.

Use Cases

At the end of this, you have a consistent workflow to build a container, deploy it for others, and then provide metadata about the container directly from your repository. It’s wicked cool! If you aren’t convinced, here are some easy use cases (that I intended to use it for). I’m a block headed engineer, I wouldn’t have built a thing if I didn’t really need it.

Experimental Paradigm Library

The experiment factory library is equivalently a collection of web based experiments, and serves a nice table to discover the repositories. However, while each repository serves it’s own web based experiment, we are still missing a setup with testing, automated deployment of containers for the experiments, and metadata for these container versions. And it’s a terrible thing because I’ve even developed a robot that could do the headless testing. Now imagine a containershare of of these experiments, where each one shows you exactly the software, versions, and Docker Hub images that are automatically built, tested, and deployed. I can integrate the containershare library table into the command to search for experiments (this will already work):

docker run vanessa/expfactory-builder list

...

97 willingness-to-wait https://www.github.com/expfactory-experiments/willingness-to-wait

98 writing-task https://www.github.com/expfactory-experiments/writing-task

99 zoning-out-task https://github.com/earcanal/zoning-out-task

but then take it a step further by having each experiment, on its own, expose complete metadata about its containers. For example, I’d want to issue another command for the writing-task that exposes the tags and containers available to me to build into my experiment container.

Sherlock Cluster Library

A component of my daily dinosaur-debugging comes down to building containers for our users for the Sherlock cluster, most of which I keep as recipes in a sherlock Github repository. It’s been eating away at me that for most of these containers, I push them manually to Docker Hub, and pull the container for the user to share on the cluster. I’ll then write up complete documentation for this generation, along with usage on Sherlock. But what if there is a different version? What if the user wants to know more about the guts of the container? What I’ve been doing is not good enough. It’s also totally lacking discoverability! If another user wants to search for containers to use that have tensorflow or keras, there is no easy means to do that. This leads into the next thing I want to talk about - a containershare command line executable. This is still in the works, but a user should be able to list and search containers directly from the containershare. I imagine usage will look like this:

# List all containers

containershare list

# Search for a tag

containershare search <tag>

This isn’t a requirement or dependency for containershare, because if you remember, there is a predictable url to get the complete manifest for the registry at https://vsoch.github.io/containershare/library.json. However, I would expect developers to be able to easily build tools around this, or integrate the json listing into their software.

I’ll likely implement this in Python and GoLang. Python isn’t “new and sexy” but it is also one of the languages of scientific programming. I’m writing this for scientists, and for them to contribute to, and there is a much higher probability of being able to do this with Python than GoLang. That said, because it’s fun (and I’m learning it) I will also develop an executable with GoLang.

Forward Tool

A tool that I’ve been developing out of Stanford with drorlab is called forward, and it comes down to simple bash scripts and ssh configurations that can easily launch sbatch jobs and then tell you how to open your browser to interact with a notebook (or similar) running on a node. I would want a user workflow with this tool to look like the following:

- Find a container you like from the sherlock containershare library

- OR don't find it, and file an issue for me to make it for you!

- Based on the tag of the container, follow an instruction to deploy it to a cluster

- Interact with the software from your local machine, without needing to ssh in, request a node, load things, and otherwise do steps that are hard to reproduce.

The container and it’s metadata are available programmatically, and on Github means we have version control and easy collaboration and reporting of issues. Instead of relying on remembering Docker Hub, Github, and/or local file paths, the containershare always makes the containers guts and discoverability transparent and easy.

Future Development

As I mentioned above, I’m working on command line clients for (more easily) getting access to metadata and searching for containers of interest. I’m also working on tutorials and examples for our users at Stanford for software on the Sherlock and Farmshare clusters. Stay tuned! I’ve been traveling heavily with no room for lovely programming and life should settle down in the coming weeks.

Background

I am learning so many cool things, but the focus that I want to talk about is the yaml file. Yaml means “YAML Ain’t Markup Language.” It’s one of these weird terms that has it’s own name in the acronym. And it’s true that it is much more than just a markup syntax. If you look at the circleci configurations that

build the containershare or

build a container repository, it looks pretty fugly if you’ve never seen it before. The first link (to the containershare configuration) is your standard design for a .circleci/config.yml (version 2.0). It has a bunch of sections that define environment, commands, and then a little section at the bottom that references the steps to run in this workflow.

YAML is Awesome!

For example, here is the start of a configuration to start with a base container, install jekyll, and build a static Github pages:

version: 2

jobs:

build:

docker:

- image: circleci/ruby:2.5.1

working_directory: ~/containershare

environment:

JEKYLL_ENV: production

NOKOGIRI_USE_SYSTEM_LIBRARIES: true

steps:

- checkout

- run:

name: Build the Jekyll site

command: |

cd docs

gem install jekyll

jekyll build

- run:

name: "Install Containershare"

command: |

wget https://repo.continuum.io/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh

/bin/bash Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh -b

$HOME/miniconda3/bin/python -m pip install pyaml containershare==0.0.12

cd $HOME/containershare/docs

$HOME/miniconda3/bin/python ../tests/circle_urls.py $HOME/containershare/docs/_site

...

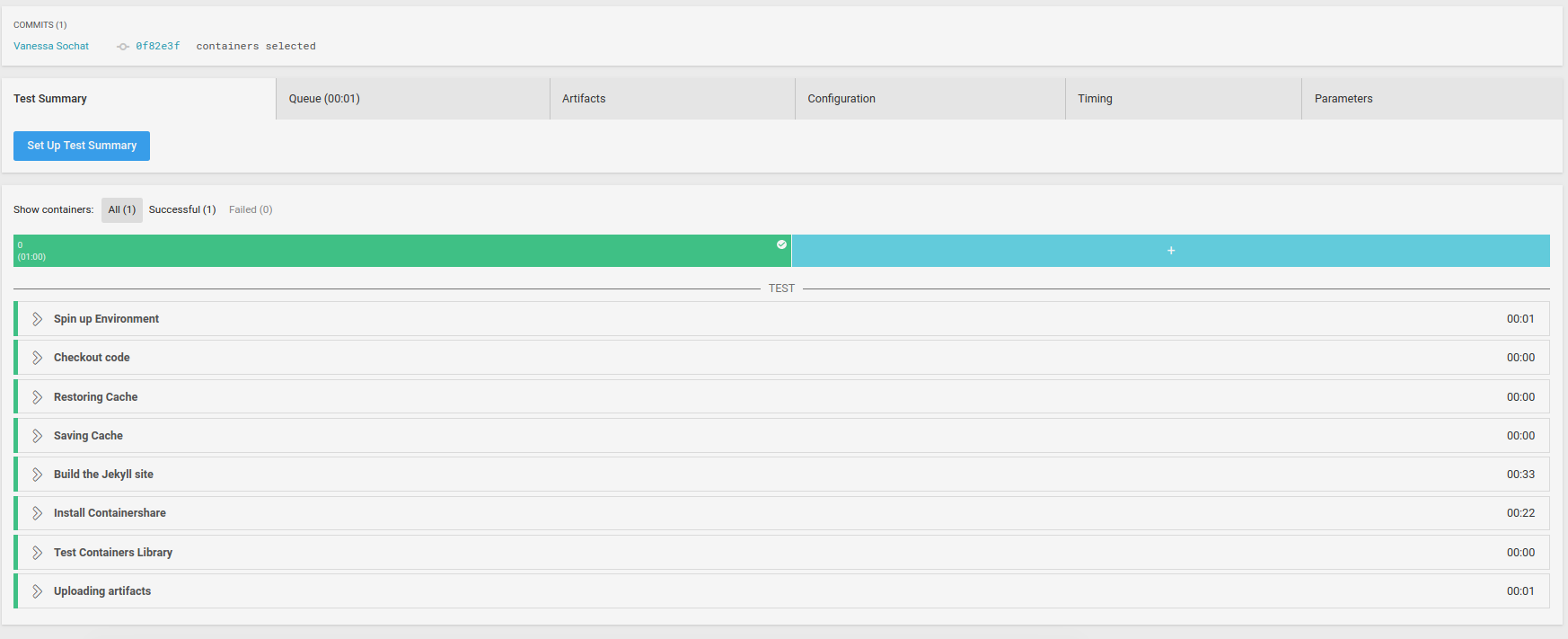

This is complicated, but you only need to write it once. In your case, you would just copy this file to your Github repository, and connect it to circle to get the same functionality. In the interface, this one job section looks like this:

and the entire workflow, defined in the bottom of this same configuration text file, references the above steps like this:

workflows:

version: 2

build-deploy:

jobs:

- build

We don’t need much more than this - to run some tests against the text files that a user submits to add to the registry. The beauty of yaml comes into play when we add many more blocks to our workflow, each called a job, and with one or more steps. For example, here is the workflow for the build->test->deploy of a container:

################################################################################

# Workflows

################################################################################

workflows:

version: 2

build_deploy:

jobs:

- build:

filters:

branches:

ignore: gh-pages

tags:

only: /.*/

- update_cache:

requires:

- build

- deploy

- manifest

filters:

branches:

ignore: /docs?/.*/

tags:

only: /.*/

# Upload the container to Docker Hub

- deploy:

requires:

- build

filters:

branches:

only: master

tags:

only: /.*/

# Push the manifest back to Github pages

- manifest:

requires:

- build

- deploy

filters:

branches:

only: master

tags:

only: /.*/

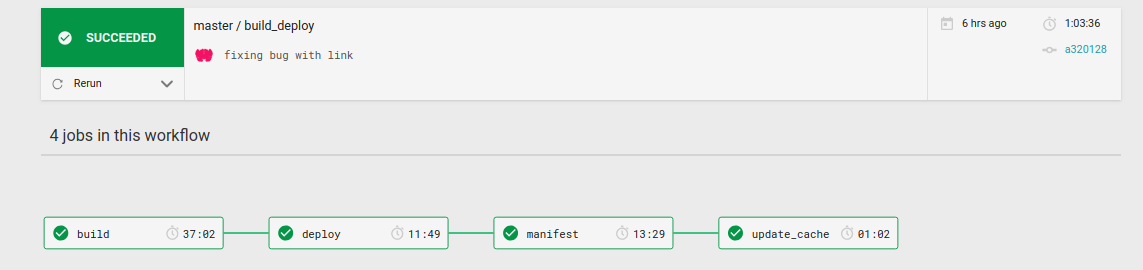

Yes, it’s much more substantial! I have logic for running things (e.g., “only run this step if the branch is master”) along with many different steps! But it’s the same deal as before - you don’t have to understand this to use it, you just copy paste the configuration, hook up to CircleCI, and you get the lovely pipeline for your container:

Anchors and Pointers are like Functions

And now here is where I am really excited. So when I first started working on this, I was troubled by repeated code. For example, I might want to load a cache in multiple build steps, or use the same environment variables. I figured out that you can use these things called anchors to bring in entire chunks of configuration, or to reference another chunk like a function! For example, here are some defaults I use across jobs, which previously would be copy pasted multiple times:

# Defaults

defaults: &defaults

docker:

- image: docker:18.01.0-ce-git

working_directory: /tmp/src

environment:

- TZ: "/usr/share/zoneinfo/America/Los_Angeles"

that are now inserted like this:

version: 2

jobs:

setup:

<<: *defaults

steps:

- run: *dockerenv

- run: *install

- run: *githubsetup

You might guess that the << is handling the magic of doing the insert so that the tags “docker” “working_directory” and “environment” fall under setup, and you are right. The

* seems appropriate because it sniffs like a pointer. What about the other pointers (e.g., dockerenv) under steps? Those are even cooler - little “functions” I’ve defined that again can be re-used! For example, here is the “function” to install Google’s container diff:

containerdiff: &containerdiff

name: Download and add container-diff to path

command: |

curl -LO https://storage.googleapis.com/container-diff/latest/container-diff-linux-amd64

chmod +x container-diff-linux-amd64

mkdir -p /tmp/bin

mv container-diff-linux-amd64 /tmp/bin

export PATH="/tmp/bin:${PATH}"

# export to bash environment

echo "export PATH=${PATH}" >> ${BASH_ENV}

and I’d insert it as a step in any job like this:

steps:

- run: *containerdiff

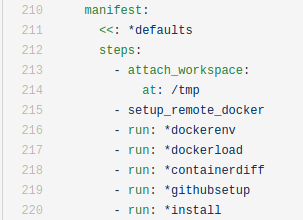

How is that for not having to copy paste? It also makes the recipe itself much more readable and user friendly. In this case, I only needed to install it once, so arguably I didn’t need this definition. But on the other hand, now I can easily read the workflow:

and if I want to use the function in another yaml workflow, I can much more easily copy paste it

than having to untangle one huge chunk of text, and then just add run: *containerdiff as a step to my recipe.

YAML Bigger Picture

I started this work, actually first contributing to the repo2docker that led to the

continuous-build

jupyter project, because I think continuous integration and testing is the next wave of huge development (and low hanging fruit) that is going to come. Specifically for reproducible science, to make it easy to have test and deploy of a version controlled, tested thing, is really amazing. People barely knew about Github when I was a graduate student. When I first reached out to CircleCI to ask about such kind of recipes, it was presented as a “for this platform only” sort of thing. I think they called the work in development “Orbs” (and I’m still super excited for this!) But when I quickly realized that yaml is yaml, and I don’t need a special CircleCI product to define functions (just anchors and pointers!) I got really excited. This opens up a call to action! for developers out there!

We need to provide template workflows for building, testing, and deploying.

When I have a repository with <my-custom-thing> I don’t want to have to do any more work than copying some

.circleci/config.yml or ._travis.yml or similar to the Github repository, and then clicking buttons. You can also imagine libraries of these “functions,” and an intelligent tool for putting them together for custom workflows on the fly. I want it to build and test my code, and also push metadata back to a web accessible place for both a human (a pretty web page) and a robot (a static API). This is what we should work on! I am sure that individual providers will provide their own “things” for achieving these sorts of goals, but you have to be careful, because if you invest too much in one particular tool, if you ever need to switch, it becomes pretty laborsome.

Summary

I hope you are as excited as me about containershare, but more importantly, the fact that you can use continuous integration recipes (and yaml!) to provide templates that do just about anything you can think of. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out or contribute to this work! I’ll have more detail on the Sherlock container library in the coming weeks. Some links that might be of interest:

- Contribute to a containershare means selecting a container repo template, adding files, and connecting to services.

- Deploy a containershare registry is even simpler - clone, connect to CircleCI, and turn on Github Pages.

- Use a containershare is currently a list of example use cases, more TBA.

For more details, see the containershare repository. I’ll likely be improving the documentation in the weeks to come, so if you want something more clearly explained, please let me know. Party on, party dinosaur friends!

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Build, Deploy, and Generate Manifests with CircleCI." @vsoch (blog), 01 Aug 2018, https://vsoch.github.io/2018/build-deploy-docs/ (accessed 01 Jul 25).