If Shrek says that happiness is just a tear drop away, I say that insight is just a 404 away. This was the content of a slack message from one of my colleagues that sent my investigatory dinosaur heart into an adventure:

ERROR Beep boop! Not Found: 404

This is a exploration, tutorial, and discussion about the challenges of building containers from the core application program interfaces (APIs) that serve information about the components. My original goal was just to pull a set of image layers and metadata from the Google Container Registry (gcr.io) into a Singularity container, but an errored pull revealed that the registry didn’t have any version 1.0 manifests, or in other terms, json data structures with important information about the environment and commands. As I worked through this, I wanted to tell the complete story of how we interact with these services, and how this does (or does not) fit the needs of different people that do said interaction. This is a long post, so if you are interested in a particular section, please jump ahead:

- Image Manifests: How do we interact with a registry for containers? Let’s talk about manifests!

- The Story of DeepVariant: I’ll tell you my Friday evening debugging that was like an unwanted dinner and a movie. I wanted to go to one restaurant to get dinner and my movie, but needed to go to two places to get what I needed.

- What did we learn?: What I learned from this experience, namely how and who tools are designed for, and if these choices have good outcomes for the people that actually use them.

Yes, this story is a bit ugly, and we may get dirty with pasta marinara on the napkin tucked neatly into our

shirt. This is my end-of-Friday hack for building DeepVariant.

Image Manifests

How do we interact with a registry?

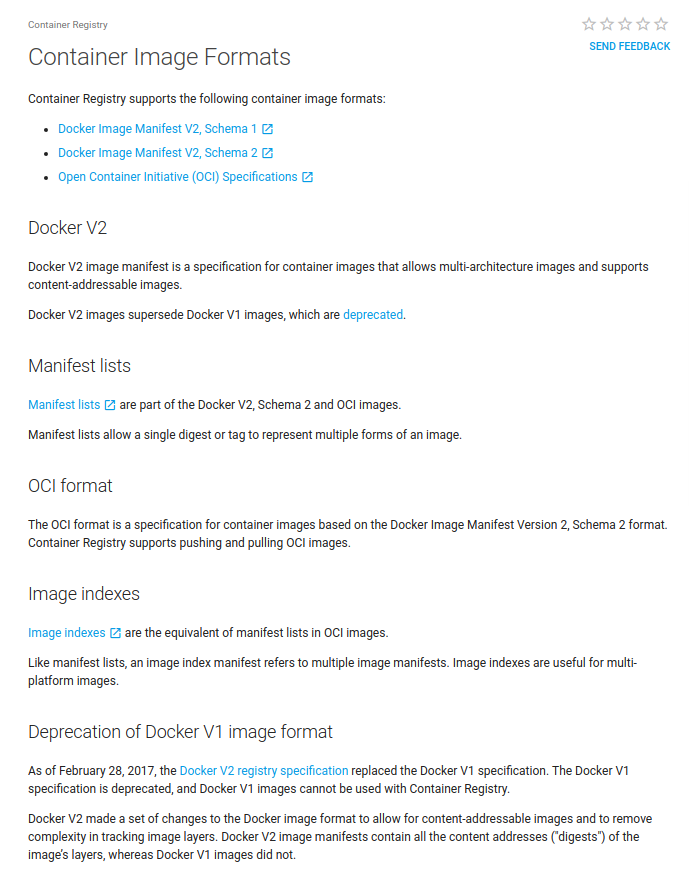

Let’s start with some basics. A registry is typically a cloud storage for metadata and files. In this case, the files and metadata are containers. You might be familiar with Docker Hub, and superpowers like Google and Nvidia have followed suit by deploying their own registries, the Google Cloud Registry, and Nvidia GPU Cloud, respectively. Hosting and then using a registry is a great way to share containers, which can be huge single or collections of files. How do we interact with a registry from our computer? We could use a web interface, but typically we interact directly or indirectly with representational state transfer (RESTful) services. Different clients have command line tools that (under the hood) use these services to perform some kind of authentication, and then make requests to interact with a unique resource identifier (uri) that is specific to an image, and a thing called a digest that could refer to a tag or a shasum. It looks like:

'https://<registry>/<name>/manifests/<digest>'

So to ask for the image with name deepvariant-docker/deepvariant from the registry gcr.io/v2 with tag 0.5.0

I would do a GET request to https://gcr.io/v2/deepvariant-docker/deepvariant/manifests/0.5.0. But that actually isn’t enough (and this takes some time to get used to, because we have this idea that urls must act like uris that are set in stone but I have yet to see this with APIs). The content that comes back is going to depend on the headers that we give it. Yes, this means that superficially the “exact same call” is going to return differently depending on headers (that you may not see from some client). This may be upsetting to you, but it actually makes a lot of sense. If we hard code variables in the urls, then any change means significant change in documentation or client side tooling. If we keep the same urls then we can just adjust the headers of the requests. If you

are an API maintainer, some would argue that it’s a lot easier for your versions to be shared across a common url schema and then use the header values as variables to drive customization. So we can usually ask

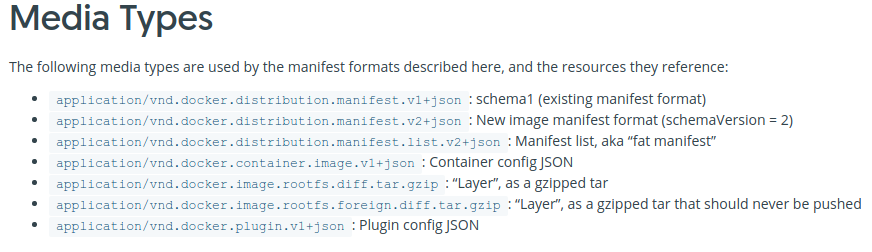

for an Accept header to determine the content type we want returned, something like application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json. And we can either get metadata (environment, entrypoint) about images from one of those special calls (more on this below).

How have manifests changed over time?

We used to (a long time ago, when the configuration was stored in the same json object as the list of image layers)

get metadata for a Docker image via the (old schema version 1.0) manifest. Here is an old manifest from Ubuntu 12.04, notice that

we have fsLayers as a list of blobsum and then a history with a v1Compatibility string that also needs to be parsed into

json:

For the interested reader, the signatures are pretty useful, and since the history is a list the user would need to iterate through the entries. It wasn’t elegant, but it reliably worked for a long time.

Schema Version 2.0

One day, when I made the typical request, our client broke because something different came back. The default manifest was now updated to schema version 2.0, and it was a sleeker, sexier pasta:

DEBUG GET https://index.docker.io/v2/library/ubuntu/manifests/16.04

{'config': {'digest': 'sha256:0458a4468cbceea0c304de953305b059803f67693bad463dcbe7cce2c91ba670',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.container.image.v1+json',

'size': 3614},

'layers': [{'digest': 'sha256:1be7f2b886e89a58e59c4e685fcc5905a26ddef3201f290b96f1eff7d778e122',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.image.rootfs.diff.tar.gzip',

'size': 42863496},

{'digest': 'sha256:6fbc4a21b806838b63b774b338c6ad19d696a9e655f50b4e358cc4006c3baa79',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.image.rootfs.diff.tar.gzip',

'size': 846},

{'digest': 'sha256:c71a6f8e13782fed125f2247931c3eb20cc0e6428a5d79edb546f1f1405f0e49',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.image.rootfs.diff.tar.gzip',

'size': 620},

{'digest': 'sha256:4be3072e5a37392e32f632bb234c0b461ff5675ab7e362afad6359fbd36884af',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.image.rootfs.diff.tar.gzip',

'size': 854},

{'digest': 'sha256:06c6d2f5970057aef3aef6da60f0fde280db1c077f0cd88ca33ec1a70a9c7b58',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.image.rootfs.diff.tar.gzip',

'size': 171}],

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'schemaVersion': 2}

to ask for this explicitly, we could set the Accept header to application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json.

You will notice instead of fsLayers we have a more logical layers. So if you had written an application to parse these manifests,

you would need to update that. The problem was, then, that different images wouldn’t always have a version 2.0 manifest, or more updated registries wouldn’t have a version 1.0. Why is this an issue? Well do you see anything missing? Yes, the metadata tidbits that were kept in the version 1.0 like CMD and ENTRYPOINT and environment (ENV) are not present. For an application, this meant that we now did two calls - asking for a version 1.0 for metadata and sometimes also using version 2.0 for the list of layers. But then, something changed, and the client broke again. The reason was because a new “list” type was added, and although the header was

suggested to be used for the Accept, it also wasn’t consistent to return. So now I started seeing lists of manifests:

DEBUG GET https://index.docker.io/v2/library/ubuntu/manifests/16.04

{'manifests': [{'digest': 'sha256:7c308c8feb40a2a04a6ef158295727b6163da8708e8f6125ab9571557e857b29',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'platform': {'architecture': 'amd64', 'os': 'linux'},

'size': 1357},

{'digest': 'sha256:d4d0d7e1905faf274dac2f5cdb9fa8f70bbebb1ccc04e22d4df3f96c14b92439',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'platform': {'architecture': 'arm', 'os': 'linux', 'variant': 'v7'},

'size': 1357},

{'digest': 'sha256:b8afe5a8067788623a7703b2c6e17c1ba8d458029dd7e51854abde307d56df8b',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'platform': {'architecture': 'arm64', 'os': 'linux', 'variant': 'v8'},

'size': 1357},

{'digest': 'sha256:df3b4d98235defcb27a6cd9c525a5d23a731114cd68c551c897e9e83c0eb151f',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'platform': {'architecture': '386', 'os': 'linux'},

'size': 1357},

{'digest': 'sha256:0d0f20b8ca0cdf704cd55e7495ad1ead53b2dd6d5f2978d487b0bcedd654d348',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'platform': {'architecture': 'ppc64le', 'os': 'linux'},

'size': 1357},

{'digest': 'sha256:9a1b70320f8d69fafb25e31cfab2b6b7e4ccdf6e169336d3db0dd2a8b8b181ce',

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'platform': {'architecture': 's390x', 'os': 'linux'},

'size': 1357}],

'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.list.v2+json',

'schemaVersion': 2}

And this coincided with an Accept header of application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.list.v2+json. As a developer

I got really excited about this one, because I could give my users different options for operating system (os) and architecture.

How has interaction changed over time?

From the above, you can tell that we’ve gone from a simple “get metadata from this endpoint” to “figure out the right endpoint to query and possibly need multiple.” In the case of a list, I have to do yet another call to retrieve a second manifest from this first. You can see how this gets complicated. Especially with an added layer of authentication and issuing a request, getting a 403 with a request for authentication, reading the Www-Authenticate header for the challenge, and then making another authenticated call to a token endpoint (we haven’t even discussed this!) there is somewhat of a large learning curve when it comes to using APIs. I would guess that the developers and documentation writers must assume this. A scientist isn’t going to sit down on an afternoon and familiarize himself with the correct regular expression for parsing the scope from the permission string to get his refresh token. He is going to use a tool that is provided (e.g., Docker or similar) or throw his hands in the air and cry silently into his ramen soup and pancakes.

The Academic Software Developer “Interface”

Arguably, the academic software engineer is the interface between this technology and custom tooling for the scientist. What does his or her interaction look like? It looks something like this:

- I have a particular goal to get information about something. I open up my terminal of choice with a method for making web requests.

- I find the minimal required command to get some server to respond in some meaningful way. This usually starts with a GET for a resource, followed by a permission denied, followed by grumbling around to make an account and save a credential somewhere, and then a token authentication, and another GET.

- I get a data structure back, and look at it. This is a joyous moment and a tiny victory. I hope that the keys are intuitive because looking things up is an extra step that I don't take off the bat.

- When I can't find something, I then look again through the documentation. If I still can't find it I resort to Google and Stack Overflow searching.

Ideally, all of this could be replaced with a simple tutorial that says “Hi Friend! Let’s walk through this together!” Unfortunately, the best of these out there are generally written by users. The Docker Hub resource, for example, serves as a massive chunk of definitions and example responses. It’s been very useful to show me parameters available, but very problematically, many times the calls that I issue don’t seem to work, and there is no nice guide that shows my particular call in completion. I want a dummy example that I can copy paste and get an immediate validation that it works. This kind of thing I usually find on Stack Overflow. I don’t see why this isn’t put up front and center. And I don’t mean to single out one documentation base - this is a chronic issue for most.

Variability is Problematic

Now let’s pretend that we figure this all out, have it programmed into an application, and things are running somewhat smoothly. Given that images are different registries serving “the same API standard” are somewhat consistent, we would do okay. This turns out to not be the case. Registries behave differently in the manifests that they serve, and images within the same registry also can have different versions. In the case of some registry providers, using a different storage requires a modified call to either add or strip a header. There are also other interesting cases, one of which we will discuss next.

DeepVariant

Everyone and their Grandpa Joe are into Artificial Intelligence (AI) and deep learning, and one of these recent models released by Google is called DeepVariant. I’m not particularly excited, but I want the researchers that I support to be able to go to town. Since this is a Google thing, and the dependencies are rather complicated, the software and model is provided in a container. This is good! The DeepVariant image is a gcr.io (Google Container Registry) image, and since this is Docker, for our users to use on a shared research cluster, we would need to convert it to a Singularity image.

Image Content (Layers)

I went through the basic steps to do this first. This isn’t the actual code from my tool, but is the basic calls summarized into their minimal set. We first get the layers list:

This works fine, because I can get the layers, dump them into my image build sandbox, and then poke around for metadata.

What was missing from what we talked about previously is any inkling of a version 1 manifest. It consistently returned 404 (not found)

when I poked at it in different ways. I then returned to the core documentation that was linked from the Google Cloud Registry site.

According to the documentation, I should be able to specify a different header to get the config.

Specifically, the one that looks like application/vnd.docker.container.image.v1+json is what we want.

I’ve tested this with some nvidia cloud images (that’s another italian restaurant story!) and it seems to work.

Otherwise I would assume that the user can fall back to asking for a version 1.0 manifest and parsing it like

a json monkey to find that beloved entrypoint (to be clear, I’m ok with being a monkey).

I’m not sure what Google is up to, because they seem to be all over the place.

Putting myself in the shoes of a general user, I’m just like <O.o> --> ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

If you look at the header for the call that did work

above, we see that this particular call was in fact using the version 2:

print(response.headers)

{

'X-Frame-Options': 'SAMEORIGIN',

'X-XSS-Protection': '1; mode=block',

'Server': 'Docker Registry',

...

'Content-Type': 'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json',

'Content-Length': '2612',

'Docker-Content-Digest': 'sha256:c95f3eba028ad8e3fe3fb4fd6fcc6ba0cd27ff14139c79bba2a9d4acc5a2591c',

'Date': 'Fri, 02 Mar 2018 21:48:35 GMT',

'Docker-Distribution-API-Version': 'registry/2.0'

}

And according to the

documentation that is linked to from their page (from Docker, thank you!) we should be able to find

the config with a media type of application/vnd.docker.container.image.v1+json. But we don’t. We get a 404. It seems from various issues

that this is a “choose your own adventure” sort of deal. The documentation tells me about all the different formats, and

even presents specific images as conforing to one or the other, but it’s no guarantee that the information I need is easy to find. Will I find a manifest for some subset of images? Maybe? If I keep trying to play around with different combinations of setting an Accept and/or a Docker-Content-Digest will I uncover the secrets? Sure, I tried that. How about the same call, but ask for the right digest:

# I think the config needs to come from another call here

print(manifest['config'])

{ 'mediaType': 'application/vnd.docker.container.image.v1+json',

'digest': 'sha256:c0acf3d54dce5eabf6ae422593a3d266e1d5d61129d53f32ec943d133b395a6c',

'size': 7601 }

# Can we try setting the Docker-Content-Digest

headers['Docker-Content-Digest'] = manifest['config']['digest']

requests.get(url, headers=headers)

# note... ignores my request and returns the same as before.

I spent an entire afternoon, evening, and night puzzling over this, and that was lost time that I (had planned) to work on other things. Don’t get me wrong, I love this kind of exploratory debugging… I live for it! But the larger idea is that this information needs to be clear and easy to find. Anyone else would have given up before starting this adventure.

Hacking together the Singularity Container

Before we talk about the “bigger picture,” let’s resolve this problem. Instead of going to one restaurant for dinner (the typical flow of API calls discussed above that should give me layers and then metadata) I dined at the first restaurant, didn’t get a portion of my dinner, went out to a street vendor for a cookie dessert, bought an additional set of napkins to clean up, and then found my own take home container to bring the goodies back.

Singularity Pull

Normally, Singularity has some back end code (originally a bash script, then python, and now being expoded in favor of GoLang) that can issue these requests to get layers and metadata. Given that gcr.io doesn’t have the version 1 manifest, this is what it looks like when you try to pull the image using Singularity:

singularity pull docker://gcr.io/deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

WARNING: pull for Docker Hub is not guaranteed to produce the

WARNING: same image on repeated pull. Use Singularity Registry

WARNING: (shub://) to pull exactly equivalent images.

Docker image path: gcr.io/deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

ERROR MANIFEST_UNKNOWN: Manifest with tag '0.5.0' has media type

'application/vnd.docker.distribution.manifest.v2+json', but client accepts 'application/json'.

Cleaning up...

ERROR: pulling container failed!

You can dig in all you want, you will discover the same deal, and the error hints that there is something weird with the media types (the Accept headers). The API endpoint isn’t what the client expects, and this is returned. Since Singularity has to be only released with very careful care, getting in a quick fix isn’t a quick thing. It also shouldn’t be the responsibility of the software to support every single specific API endpoint snowflake. Thus, for reasons like this, I develop with Singularity Global Client (sregistry) that has endpoints for all these various cloud storages, and is optimized for quick, open source development to address weird (endpoint specific) issues. This is another quick lesson for software development that I hold true, you may or may not agree:

Don’t package highly error prone and changing APIs with core software.

The reason is because they will need to be updated and debugging quite frequently, and this pace may be faster than the core software can keep up. This means that users will be frustrated, and generally waiting on you. Instead, it makes sense to have supporting tools (sregistry is really just a wrapper that let’s the user do a custom install and specification of his or her favorite endpoints) that can be very quickly updated. In the case of the error above, I had debugging and updated the package in under an hour. Now let’s review the entire hack for building this deepvariant Singularity image!

Pull

We saw above that we can’t used Singularity to pull, so here let’s look at using sregistry to get our layers. First we will pull. Since there is no version 1.0 of anything, we only get layers and no metadata. The client gives us this warning.

sregistry pull docker://gcr.io/deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

[client|docker] [database|sqlite:////home/vanessa/.singularity/sregistry.db]

WARNING No metadata will be included.

Exploding /usr/local/libexec/singularity/bootstrap-scripts/environment.tar

...

WARNING: Building container as an unprivileged user. If you run this container as root

WARNING: it may be missing some functionality.

Building FS image from sandbox: /tmp/tmpeqpqhiqs

Building Singularity FS image...

Building Singularity SIF container image...

Singularity container built: /home/vanessa/.singularity/shub/deepvariant-docker-deepvariant:0.5.0.simg

Cleaning up...

[container][new] deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

Success! /home/vanessa/.singularity/shub/deepvariant-docker-deepvariant:0.5.0.simg

Here is the image file.

sregistry get deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

/home/vanessa/.singularity/shub/deepvariant-docker-deepvariant:0.5.0.simg

Great! We have the image content in that file, but no metadata about the environment or commands (entry points). This is something that we also need! It is in fact the case that these two sources of information come from different API calls. Any sense that they come from one place is usually concealed by the client.

Metadata

I spent quite a bit of time struggling to find this information from the various APIs, and it was largely a fail bus. Let’s pull the image from Docker and the Daemon will do it’s magic that (if I spent enough time looking through their source code) I could possibly find the secret call to get the config blob.

docker pull gcr.io/deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

Now we can inspect it to get that metadata. I’ll just show the parts that I care about, and I put the entire thing here if ever it’s needed:

In summary, I need the environment and the entrypoint. The other stuff is great, but I could probably do ok without.

Recipe Writing

Let’s now create a Singularity recipe with all these things. Now if only all this information could be represented in one place like this! My first try used the manifest above, and the entrypoint was ugly. Instead of parsing the CMD from the json above, I just found the original source. The final build recipe is here, and I’ll comment on the seconds below:

The above is great, but it’s problematic for reproducibility because we are using a local image file as a base, and not something from a web endpoint. This was my strategy for the time being, since this was such a messy operation to begin with and I wasn’t even sure it would lead to a successful image build.

Building, Building, Building

To perform the build with the recipe above, a file called Singularity we can do:

sudo singularity build deepvariant Singularity

Notice that we are building from a local image, specifically the one that I pulled and built with sregistry. The path was revealed with sregistry get and when I lose that path in a few months, I can run that command again and sregistry serves as a database to remind me of it. I then realized that there were multiple entrypoints, and instead of chucking out some long “usage” description, I’d make it easier for the user by providing the entry points as internally modular Scientific Filesystem applications. I then realized that in running any application there was an expectation of input data, or at least for this example container, that the user download the example data. So I found it here,

and added another SCIF entrypoint for it (notice all the wgets). I could then give simple instructions for running each step as the main entrypoint, given that the user didn’t ask for anything.

Interaction and Discoverability

Let’s see what we get when we just run the image, pretending we haven’t a clue what it does.

./deepvariant

Example Usage:

# download data to input and models

singularity run --app download_testdata deepvariant

singularity run --app download_models deepvariant

# make the examples, mapping inputs

singularity run --bind input:/dv2/input/ --app make_examples deepvariant

# call variants, mapping models

singularity run --bind models:/dv2/models/ --app call_variants deepvariant

# postprocess variants

singularity run --bind input:/dv2/input/ --app postprocess_variants deepvariant

# https://github.com/google/deepvariant/blob/master/docs/deepvariant-docker.md

Since I added a bunch of scientific filesystem applications, the Singularity integration of SCIF will let us list those:

singularity apps deepvariant

call_variants

download_models

download_testdata

make_examples

postprocess_variants

Data

We can then follow the instructions we saw above and download data. This downloads to a folder called input

and models in the $PWD, since Singularity has a pretty

seamless environment between host and container. We don’t need to worry about mapping things like with Docker.

singularity run --app download_testdata deepvariant

singularity run --app download_models deepvariant

Having data as external was a choice in design. It can’t be guaranteed that this is the exact model that is wanted, and we definitely don’t want to put large files in the container. A better script would take the name of data as input (if you look at the recipe above we just hard code it to the examples name) but this is fine for the purposes of this exercise. Finally, it was also strategic to make the download of input and models separate, because a user might want to use them selectively. An entire set of apps might be provided to just download from different sources, for example. We can quickly glance at the data and models that were downloaded:

ls input/

NA12878_S1.chr20.10_10p1mb.bam test_nist.b37_chr20_100kbp_at_10mb.vcf.gz.tbi

ucsc.hg19.chr20.unittest.fasta.gz.fai ucsc.hg19.chr20.unittest.fasta.gz.gzi

NA12878_S1.chr20.10_10p1mb.bam.bai ucsc.hg19.chr20.unittest.fasta

test_nist.b37_chr20_100kbp_at_10mb.bed ucsc.hg19.chr20.unittest.fasta.fai

test_nist.b37_chr20_100kbp_at_10mb.vcf.gz ucsc.hg19.chr20.unittest.fasta.gz

ls models

model.ckpt.data-00000-of-00001 model.ckpt.index model.ckpt.meta

For this next command, since stuffs is expected in some directory called /dv2/inputs we have to map that. We then go between mapping the models folder and nothing, since the $PWD with our outputs is automatically bound with Singularity (note this depends on the configuration file, meaning that a cluster might choose to disable this but it’s unlikely.

Run the Thing

At this point we have our container, we’ve seen how it works, and we want to run-the-thing. We finish up running with these steps:

singularity run --bind input:/dv2/input/ --app make_examples deepvariant

singularity run --bind models:/dv2/models/ --app call_variants deepvariant

singularity run --bind input:/dv2/input/ --app postprocess_variants deepvariant

The output is an output.vcf (variant calling format) file that has all the answers to life, universe, and everything. While the entire process above could be automated, the need for the docker daemon and that I ultimately found resources to download with the web interface (and that these resources might change, period) makes this build brittle. If we could reliably capture the metadata with our download of layers, or just download an entire pre-built image binary, we might do better. More importantly, I am nervous that this routine would be hard for a scientist to figure out and then run and maintain.

What this should have been

Okay, let’s step back and pretend that things worked as they should have. Do you know how easy this could have been?! It could have looked like this:

singularity pull docker://gcr.io/deepvariant-docker/deepvariant:0.5.0

singularity run --app download_testdata deepvariant

singularity run --app download_models deepvariant

singularity run --bind input:/dv2/input/ --app make_examples deepvariant

singularity run --bind models:/dv2/models/ --app call_variants deepvariant

singularity run --bind input:/dv2/input/ --app postprocess_variants deepvariant

I literally could have copy pasted that from somewhere, pressed control+v, and gone off for a run. The one detail I didn’t mention is that the container seems to require that I have local Google credentials (or at least acknowledge them) so there may be a different outcome if the user does not. This would be a small additional need, still, because it’s not hard to download these, so your every call and use of the products is logged for the big machine learning algorithm in the sky. But instead, we are now 12+ hours later and I’m wondering why something that is presented as so cool and easy was in fact very hard. Don’t judge, this is how I like to spend my Friday nights! Time to discuss what we learned.

What did we learn?

I learned a lot from yesterday, which has now blended into today. First, this is a simple and powerful example of why having a plug and play container on Google Cloud (Google Container Registry or similar) isn’t good enough for the common scientist. Why? Let’s put ourselves in the shoes different people.

The Graduate Student

The Graduate Studhent doesn’t have money to spend on Google Cloud. So he goes through the test example and uses Docker on his local machine, and follows one of the tutorials. Great! It’s weird with so many cloud APIs and commands with a mysterious gsutil and gcloud that somehow connects things, but that’s OK, the black box works. But now it’s time to run on his data. And remember that he can’t plug one of his three credit cards that plugs into his seriously underfunded graduate stipend to run this at scale. So he goes to his local research computing center (if he has one) and begs for an install of deepvariant. The administrator cringes looking at the dependencies, and then some time later struggles through the raw install routine of deepvariant as some module for the user to load, and all is well. Well, all is well until two days later when there is a new version, and then we have to do it again. What are the problems here?

- the graduate student is beckoned with the latest and greatest technology, but is severely lacking in resources to use it

- the technology is not developed or deployed to support his use case, and resources

The HPC Administrator

For the HPC administrator or anyone that is helping the graduate student, they are playing the role of some kind of middleman. Akin to the graduate student, we are likely dealing with a small (also underfunded) team to do some conversion of “modern” to “runs on our system securely.” Although we all love Docker, we’d be insane to install it on a SLURM cluster, a shared resource, for example. So we have a few options:

- we either do some kind of container conversion, which usually results in loopholes and hacks to get everything working again. This is largely what I do. I figure out how to turn things from Docker to Singularity.

- we forget the containers and just install on bare metal.

Of course the first option is, by way of being a hack, not going to be easy to maintain. Given that the “one line command” to pull a docker image actually works (and there are many bugs one might hit) this is at least a reasonable approach to produce a single image binary. The second option, of course, might be more stable but then require the small team to do it all again when there is an update. Which, as we know with these technologies, is incredibly slow, right? not.

The Interaction

And now we can address the interaction between the two parties above. I’ve been on both sides of the coin here, so I can now understand how this might work. The work itself takes some time, and is repetitive. This means that the graduate student, who thinks of the task simply as “install the thing so I can use it” might be impatient if it takes time to figure out how to do that. The HPC admin, on the other hand, may not feel so joyous having to do this routine X number of times and for every special piece of software that does machine learning / AI / or sprocket sorting that comes out. You could very easily follow Silicon Valley software trends based on tracking user requests for them on a research cluster, I suspect.

Software Engineer

Now let’s talk about my boat, the software engineer. I am terrible as an HPC admin, and mediocre as a software engineer, but I span the two spices nicely enough to understand the challenges and needs of both. I want to be able to use the minimum amount of “modern” resources to build something that is reproducible and runs on HPC. This was the first driver for the early conversion script of Docker to Singularity, and now the core of Singularity that makes it possible, period, for a researcher to run any Docker image, as we might have done above:

singularity shell docker://ubuntu:14.04

In summary, here are the problems that I ran into.

- The documentation that was referenced with the resource with regard to how to request a particular "config" manifest was misleading. There was no version 1.0 or container.image manifest easily findable that I could figure out. I could only intuit that some versions were missing based on error reports.

- On many occasions it was a "guess and hope for the best" sort of deal. With unclear documentation, my best option is to try all possible combinations of things, and try to put myself in the designers of the API shoes to guess what would be logical to have.

- here was conflict between what header, and then value for the header, would give me what I wanted. Should I specify an `Accept` with a manifest version, or the `Docker-Content-Digest` or both? Or something else entirely?

- There was an additional variable in a returned response (config) that should have given me a `sha256` sum to specify a digest that I wanted, and return the config. It didn't.

In the end I had to dig into the core API (hitting issues that I couldn’t figure out) using my own tool (to bypass errors hit by the production Singularity) then unwrap the original image build from it’s various source code (thank you, Github!), use different “backdoor” methods to get the same information in another way (Docker client), figure out how to put the two together (Singularity recipe), do the build and test it to figure out host binding, translate a call to a Google utility and url for a gs:// (Google Storage) dataset to be obtainable with basic technology (wget), and then expose the multiple entrypoints for myself (or the user) with a Scientific Filesystem. Holy moly! That was done in the time between the “end of day” and “starting dinner.”

Reproducibility

Let’s say that I’m a scientist, and I just spent my weekend figuring this out. I have this solution, and my container, and today we are having creamy ramen for dinner to celebrate! I would first write my build steps into a recipe. Here is the first place I could go wrong - if I rely on sregistry I would need to also account for the version.

sregistry version

0.0.71

The same is true for the version I asked for when I pulled the Google Container Registry image. Assuming that the resource lasts forever (…?) I should have asked for a specific sha256 sum. There is also a huge dependency on my local machine’s Docker version, which I hackily used to get the configuration metadata. Arguably, I’d do that once, and just pray that it doesn’t change too frequently. Realistically I would use my Singularity build recipe and only investigate when something broke. If it silently broke? Ruhroh. If I was a little more investigatory and stubborn, I would dig into the Docker client itself and find the API that seems to work using it to get the same manifest, and then go back and fix my first method. The common scientist probably doesn’t have time to do that. After all of this we can generally ask - is the build reproducible? The answer is no. The build is hacky and fragile. What is reproducible is the final single image binary that I come up with. I could dump that on a server somewhere are share with one stupid wget or curl equivalent. Then the harder part comes with sharing data and file formats, but let’s not go into that rabbit hole today.

Summary

So here is what I learned today from this exercise. My entire functioning to map the world of “modern stuffs” to “works on HPC with SLURM” relies upon the resources that I use providing clear and accurate documentation. It’s easy to find on Google documentation for using their cloud resources, and this makes sense, because they want you to pay for it.

Missing Eyes for the Bugs

Is it Google’s “fault” for not making it easy enough for me? I don’t think so. I think we are actually dealing with an interesting situation here - two very different entities that share the same goals (do the science!) both having blindspots.

Academia is missing a layer of software engineers, industry is missing a layer of reproducibility engineers.

I’ve thought about academic software engineers before and what they provide. I haven’t before thought about the person sitting on the other (industry) side of this need. I use the term “reproducibility engineer” to refer to a subtype of software engineer that bridges the world of industry and academia. The engineer cares a LOT about documentation, versioning, how the tool is used in the wild.

The industry reproducibility engineer approaches different tools offered from the viewpoint of “How would this subtype of user interact with this, and where does this interaction break?” It’s not really the same as some kind of user interaction designer (or what the title may be) that seeks out clients and ask them questions about how they like things. This is likely a full stack engineer that can serve dually as a software engineer but is also a well seasoned potato in having first hand understanding of what the users are actually doing. This actually means minimal time (sometimes wasted) arranging meetings to ask clients questions that, although may be relevant, they can’t really provide actionable answers to.

The reproducibility engineer is also not assigned to a particular product team. He or she is given an (almost) “final” thing, pointed at the documentation, and then “Go.” He or she is a expert at breaking things, and coming at things from many different perspectives. Some might argue that the task of assessing usage should come from the same team that generates the tooling. The problem with working on a particular product team, or even in a particular academic group, is that you get tunnel visoin to the working conditions and environment that you have. When you learn the skillset to be a software engineer at Google, or a member of an academic lab, your entire approach to solving problems is scoped to that. If you are lucky, you use technologies that are embraced by other groups that you might work with. In a closed or large company you are more likely to be using a proprietary internal infrastructure that, when you leave, you realize you can only take away with you general practices for software engineering to map to other things.

Why might it be that we don’t have this? Because the pace needed to develop technologies to keep up with the Silicon Valley gerbil treadmill is too fast to put in the extra time and resources to debug these edge use cases. The technology changes so quickly that it arguably wouldn’t be a good use of time. But it ironically hurts many users in this “long tail” of science that do face those edge cases. In the defense of industry, the documentation that is provided is generally up to date, and even beautiful. The problem is the scope of the user it is intended for is not clearly defined. The goals of the company may not be to directly support these edge cases, but everyone wins if there is an interface between the two worlds: even a small set of people that purely work to support the interaction.

How do we do better?

This goes into territory that calls for change. The fact that it wasn’t easy to find a working command for interacting with their API via other means, such as with basic RESTful calls (or an equivalent client) is hurting academic science. It’s hurting science because it means that the software engineer can’t easily harness the tools that the scientist needs to use the modern technology on the only resource he has. If our goal is empowering scientists to make discoveries, and we are aware of the challenges that they face, one of these flows of information needs to be strong:

[ resource ] --> [ tool ] --> [ scientist ]

[ resource ] --> [ API ] --> [ research software engineer] --> [ tool ] --> [ scientist ]

For case 1, the base tool (for example Docker) is fully usable by the end user (scientist) so no additional help is needed. For case 2, the tool isn’t friendly to the scientist’s environment so a middleman (software engineer) is needed. So instead of this obsession with AI and black box models that you can show off but not easily share, how about an obsession with clear documentation that reflects actual standards that are implemented and work? Or easy avenues to directly ask a question or get support without hours of searching Stack Overflow and manually testing headers with hope of stumbling on the right answer? The question that I don’t know the answer to is what would be the incentive structure to warrant a big company taking the extra resources to exposure their tooling clearly to multiple audiences. I can’t imagine that having more and different users could be hurtful.

If the product is intended for science, then it must be for scientist. But if it’s for scientists, then why isn’t it optimized to run where they can run things, or why isn’t support provided to help with that?

We can do better.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Google Container Registry Metadata 404." @vsoch (blog), 03 Mar 2018, https://vsoch.github.io/2018/deepvariant/ (accessed 03 Jan 26).