If you are like me, you probably peruse a million websites in a day. Yes, you’re an internet cat! If you are a “tabby” then you might find links of interest and leave open a million tabs, most definitely to investigate later (really, I know you will)! If you are an “Octocat” then “View Source” is probably your right click of choice, and you are probably leaving open a bunch of raw “.js” or “.css” files to look at something later. If you are an American cat, you probably have a hodge-podge of random links and images. If you are a perfectionist cat (siamese?), you might spend an entire afternoon searching for the perfect image of a donut (or other thing), and have some sub-optimal method for saving them. Not that I’ve ever done that…

TLDR: I made a temporary stuff saver using service workers. Read on to learn more.

How do we save things?

There are an ungodly number of ways to keep lists of things, specifically Google Docs and Google Drive are my go-to places, and many times I like to just open up a new email and send myself a message with said lists. For more permanent things I’m a big fan of Google Keep and Google Save, but this morning I found a use case that wouldn’t quite be satisfied by any of these things. I had a need to keep things temporarily somewhere. I wanted to copy paste links to images and be able to see them all quickly (and save my favorites), but not clutter my well organized and longer term Google Save or Keep with these temporary lists of resources.

Service Workers, to the rescue!

This is a static URL that uses a service worker with the postMessage interface to send messages back and forth between a service worker and a static website. This means that you can save and retrieve links, images, and script URLS across windows and sessions! This is pretty awesome, because perhaps when you have a user save stuff you rely on the cache, but what happens if they clear it? You could use some kind of server, but what happens when you have to host things statically (Github pages, I’m looking at you!). There are so many simple problems where you have some kind of data in a web interface that you want to save, update, and work with across pages, and service workers are perfect for that. Since this was my first go, I decided to do something simple and make a resource saver. This demo is intended for Chrome, and I haven’t tested in other browsers. To modify, stop, or remove workers, visit chrome://serviceworker-internals.

How does it work?

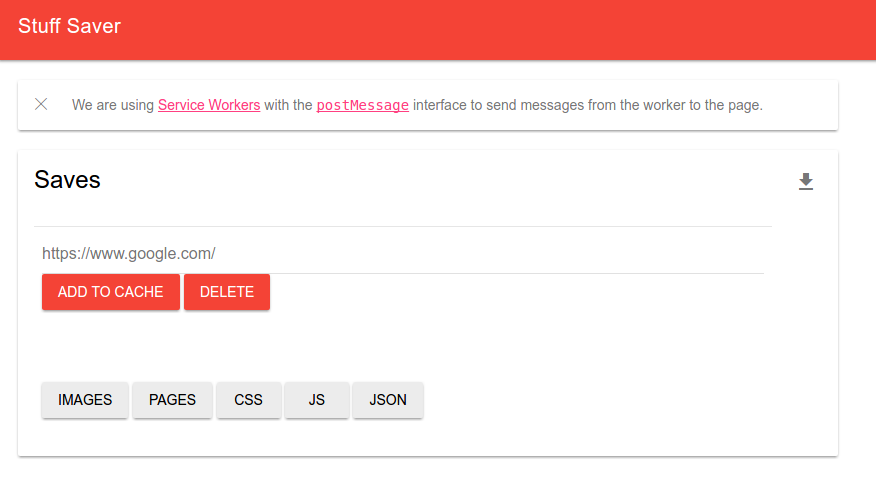

I wanted a simple interface where I could copy paste a link, and save it to the cache, and then come back later and click on a resource type to filter my resources:

I chose material design (lite) because I’ve been a big fan of it’s flat simplicity, and clean elements. I didn’t spend too much time on this interface design. It’s pretty much some buttons and an input box!

The gist of how it works is this: you check if the browser can support service workers:

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

Stuff.setStatus('Ruh roh!');

} else {

Stuff.setStatus('This browser does not support service workers.');

}

Note that the “Stuff” object is simply a controller for adding / updating content on the page. Given that we have browser support, we then register a particular javascript file, our service controller commands, to the worker:

navigator.serviceWorker.register('service-worker.js')

// Wait until the service worker is active.

.then(function() {

return navigator.serviceWorker.ready;

})

// ...and then show the interface for the commands once it's ready.

.then(showCommands)

.catch(function(error) {

// Something went wrong during registration. The service-worker.js file

// might be unavailable or contain a syntax error.

Stuff.setStatus(error);

});

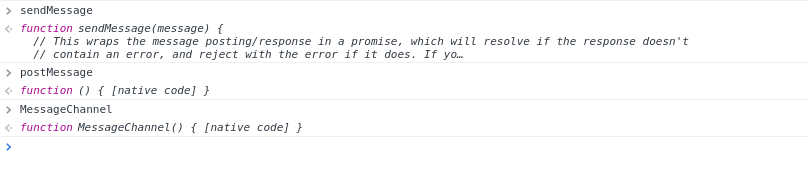

The magic of what the worker does, then, is encompassed in the “service-worker.js” file, which I borrowed from Google’s example application. This is important to take a look over and understand, because it defines different event listeners (for example, “activate” and “message”) that describe how our service worker will handle different events. If you look through this file, you are going to see a lot of the function “postMessage”, and actually, this is the service worker API way of getting some kind of event from the browser to the worker. It makes sense, then, if you look in our javascript file that has different functions fire off when the user interacts with buttons on the page, you are going to see a ton of a function saveMessage that opens up a Message Channel and sends our data to the worker. It’s like browser ping pong, with data instead of ping pong balls. You can view in the console of the demo and type in any of “MessageChannel”, “sendMessage” or “postMessage” to see the functions in the browser:

If we look closer at the sendMessage function, it starts to make sense what is going on. What is being passed and forth are Promises, which help developers (a bit) with the callback hell that is definitive of Javascript. I haven’t had huge experience with using Promises (or service workers), but I can tell you this is something to start learning and trying out if you plan to do any kind of web development:

function sendMessage(message) {

// This wraps the message posting/response in a promise, which will resolve if the response doesn't

// contain an error, and reject with the error if it does. If you'd prefer, it's possible to call

// controller.postMessage() and set up the onmessage handler independently of a promise, but this is

// a convenient wrapper.

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

var messageChannel = new MessageChannel();

messageChannel.port1.onmessage = function(event) {

if (event.data.error) {

reject(event.data.error);

} else {

resolve(event.data);

}

};

// This sends the message data as well as transferring messageChannel.port2 to the service worker.

// The service worker can then use the transferred port to reply via postMessage(), which

// will in turn trigger the onmessage handler on messageChannel.port1.

// See https://html.spec.whatwg.org/multipage/workers.html#dom-worker-postmessage

navigator.serviceWorker.controller.postMessage(message,

[messageChannel.port2]);

});

}

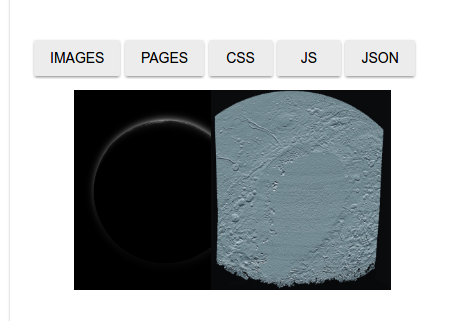

The documentation is provided from the original example, and it’s beautiful! The simple functionality I added is to parse the saved content into different types (images, script/style and other content)

…as well as download a static list of all of your resources (for quick saving).

More content-specific link rendering

I’m wrapping up for playing around today, but wanted to leave a final note. As usual, after an initial bout of learning I’m unhappy with what I’ve come up with, and want to minimally comment on the ways it should be improved. I’m just thinking of this now, but it would be much better to have one of the parsers detect video links (from youtube or what not) and then them rendered in a nice player. It would also make sense to have a share button for one or more links, and parsing into a data structure to be immediately shared, or sent to something like a Github gist. I’m definitely excited about the potential for this technology in web applications that I’ve been developing. For example, in some kind of workflow manager, a user would be able to add functions (or containers, in this case) to a kind of “workflow cart” and then when he/she is satisfied, click an equivalent “check out” button that renders the view to dynamically link them together. I also imagine this could be used in some way for collaboration on documents or web content, although I need to think more about this one.

Suggested Citation:

Sochat, Vanessa. "Service Worker Resource Saver." @vsoch (blog), 10 Jul 2016, https://vsoch.github.io/2016/service-worker-resource-saver/ (accessed 01 Jul 25).